Can a Museum Rewrite Art History?

Ask me to build a Mount Rushmore of Abstract Expressionism, and I’ll put the faces of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman up there. From Hollywood movies to MoMA retrospectives to award-winning dramas, those figures stand in the popular imagination as the first rank of their generation. A newly opened museum hopes to carve a niche for another face in that pantheon—Clyfford Still. The Clyfford Still Museum, which opened on November 18th in Denver, Colorado, exists specifically to push Still over the top and undo decades of neglect of his art. The story behind that neglect—a self-imposed isolation—is also the story behind this hoped-for resurrection. Can The Clyfford Still Museum rewrite half a century of American art history?

Although one of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists, Still sold only about 150 paintings during his lifetime, not from a lack of demand, but rather from an unwillingness by the author to engage with the world around him. “I am not interested in illustrating my time,” Still explained. “A man’s ‘time’ limits him, it does not truly liberate him. Our age—it is one of science, of mechanism, of power and death. I see no point in adding to its mechanism of power and death. I see no point in adding to its mammoth arrogance the compliment of a graphic homage.” While others (including the arts wing of the U.S. government) presented Abstract Expressionism as a shining example of American freedom in contrast to the repressiveness of Communist Russia during the Cold War, Still refused to allow his art to participate in the zeitgeist, choosing instead to become a sort of ghost himself, elusively haunting the halls of art history.

When Still died in 1980, he specified in his will that his collection of his own works—2,400 in all (approximately 825 paintings and 1,575 works on paper) or 94% of his oeuvre—be entirely sealed away from the public and academics. For nearly three decades no scholars have been able to view the vast majority of Still’s art. A select few museums hold examples of Still’s work, but those glimpses only tantalized the scholars who pursued this artist resisting his pursuers from the grave. Still left it to his widow, Patricia, to find an American city willing to erect a permanent museum for his collection. Denver finally won the bid in 2004 with promises to follow the will to the letter, including vows to never sell or loan works or include a restaurant or auditorium on the site. With this opening, the entombment of Still’s will now becomes the grand palace of his prowess.

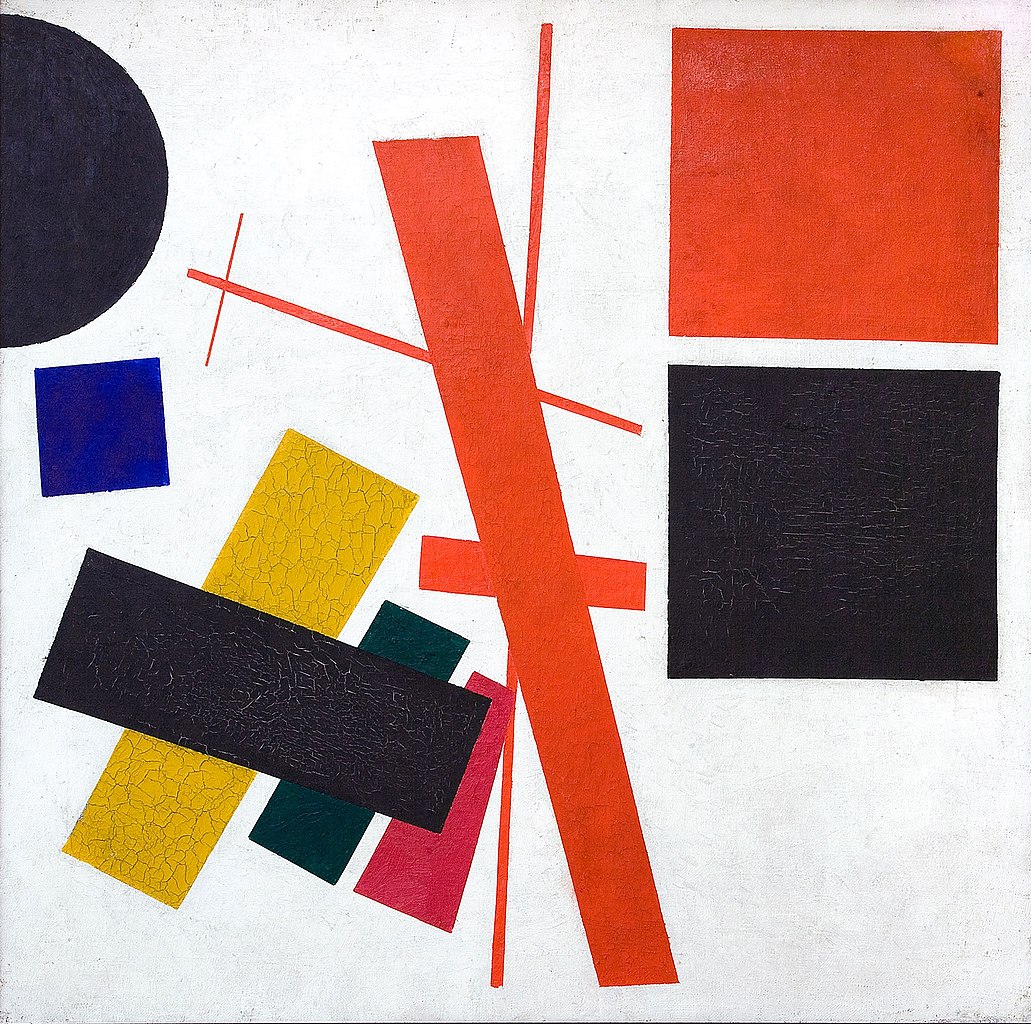

Finally, a generation of scholars that could only read about Still can judge for themselves and, more importantly, write the new history of the period, but now including Still in his rightful position. Masterpieces such as Still’s 1957-J No. 2 (PH-401) (shown above) will be studied in detail. Still’s relentless abstraction, as can be seen even in his titles (the “1957” of the painting’s title refers to the year it was made, with the rest being Still’s personal code), makes getting close difficult at times, but the imagery itself inspires you to soldier on.

Whether the public will get turned on to Still may be a bigger challenge. Without loans to other museums, The Clyfford Still Museum will have to attract patrons to Denver to see the collection. I’m no legal scholar, but I’m curious to see if the museum eventually tries to challenge that part of the will, similar to the way The Barnes Foundation went to court to break the no-loans conditions of Dr. Albert Barnes’ will in the name of sorely needed revenue. The Clyfford Still Museum recently sold four paintings by Still for a total of $114 million arguing that the museum had not yet opened, so the collection wasn’t a “collection” yet and, therefore, available for sale to garner operating costs. The maneuver sounds like skillful skirting of the semantics of the Still will and may be a harbinger of future legal dealing in the name of preserving and promoting the museum and the man.

It will be fascinating to watch how The Clyfford Still Museum accomplishes its mission. Three decades of silence is a difficult thing to overcome, especially with the restrictions they’re faced with. But they chose to take on the challenge, and I wish them all the luck in the world. For all we know, or think we know, of the Abstract Expressionists from the big screen to the intimate stage, meeting Clyfford Still—not just one of them, but one of the best—for what amounts to the first time for generations will be a startling, and thrilling, experience.

[Image:Clyfford Still. 1957-J No. 2 (PH-401), 1957. Oil on canvas, 113 x 155 in. Clyfford Still Museum Collection. © Clyfford Still Estate. Photo: Peter Harholdt.]

[Many thanks to The Clyfford Still Museum for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to their grand opening.]