How Elmyr de Hory, the most successful art forger in history, made $50 million

- Elmyr de Hory used his talent of copying the style of other painters to sell forgeries to galleries across Europe.

- De Hory’s legacy is venerated in Orson Welles’ documentary F for Fake, which explores the relationship between art and illusion.

- The documentary argues that forgers deserve our respect because making art is an inherently collaborative process and nothing is original.

Ibiza has been called home by many colorful characters, but in the 1960s, no other island resident inspired as much intrigue as Elmyr Dory-Boutin. He could be recognized by his golden monocle, patterned cravats, and elusive accent. Like Gatsby, he threw lavish parties in an out-of-time villa overlooking the sea. Among the guests were celebrities Marlene Dietrich and Ursula Andress who, ogling at Dory-Boutin’s collections of priceless Parisian paintings, suspected their host was of royal blood.

They were wrong. Just as Gatsby confided in Nick Carraway, so too did Dory-Boutin eventually open up to his own neighbor, a journalist named Clifford Irving. He was not of royal blood, and the paintings displayed in his villa were neither priceless nor Parisian; they were fakes, fakes he had forged himself and sold to galleries and oil tycoons using fake identities. Dory-Boutin was one of those fake identities. His real name, supposedly, was Elmyr de Hory.

Most of what we know about de Hory’s early existence comes to us from a biography that Irving went on to write, titled Fake! The story of Elmyr de Hory, the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time. According to the book, de Hory was born in Budapest. He discovered his artistic talents at an early age and cultivated them at a number of institutions, but suffered an existential crisis upon realizing that classical painting — the kind of painting he studied and adored — was rendered obsolete by Fauvism, Expressionism, and Cubism.

How Elmyr de Hory started forging

Had de Hory lived a century earlier, he would have had little trouble making a living off his work. Presently, his situation was made all the worse by the Great Depression, a worldwide financial crisis that pulled many buyers out of the art market. Depression was followed by war, part of which de Hory might have spent in Transylvania, where he was imprisoned for political dissent. The openly gay painter also claims he saw the inside of a German concentration camp before Hitler was defeated.

Post-war France posed the same problems for de Hory’s career as pre-war France. He struggled to sell his paintings, and was seriously considering switching careers when, one unsuspecting day, he sold a little pen-and-ink drawing to a woman who mistook the work for a Picasso. Imitating the style of other painters, a reinvigorated de Hory went from gallery to gallery presenting what curators believed were never-before-seen Picassos, Matisses, and Modiglianis.

De Hory continued selling forgeries for years. When someone finally caught on, it was not because they noticed differences between de Hory’s paintings and the artists he was imitating, but because they found small similarities among the forgeries themselves. De Hory escaped to Ibiza where, thanks to various legal loopholes, he lived without fear of apprehension until his suicide in 1976. Today, experts estimate his fakes sold for over $50 million, making him one of the most successful forgers of all time.

The value of forged art

Like many forgers, de Hory is remembered as a great conman and not as a great artist — strange, considering his fakes were flawless to the point that even the most seasoned critics believed that they were the real deal. Before de Hory’s cover had been blown, galleries were willing to put down massive sums of money for his paintings. Once the scam was revealed, however, those exact same paintings were deemed worthless, taken down, and tossed in the nearest dumpster.

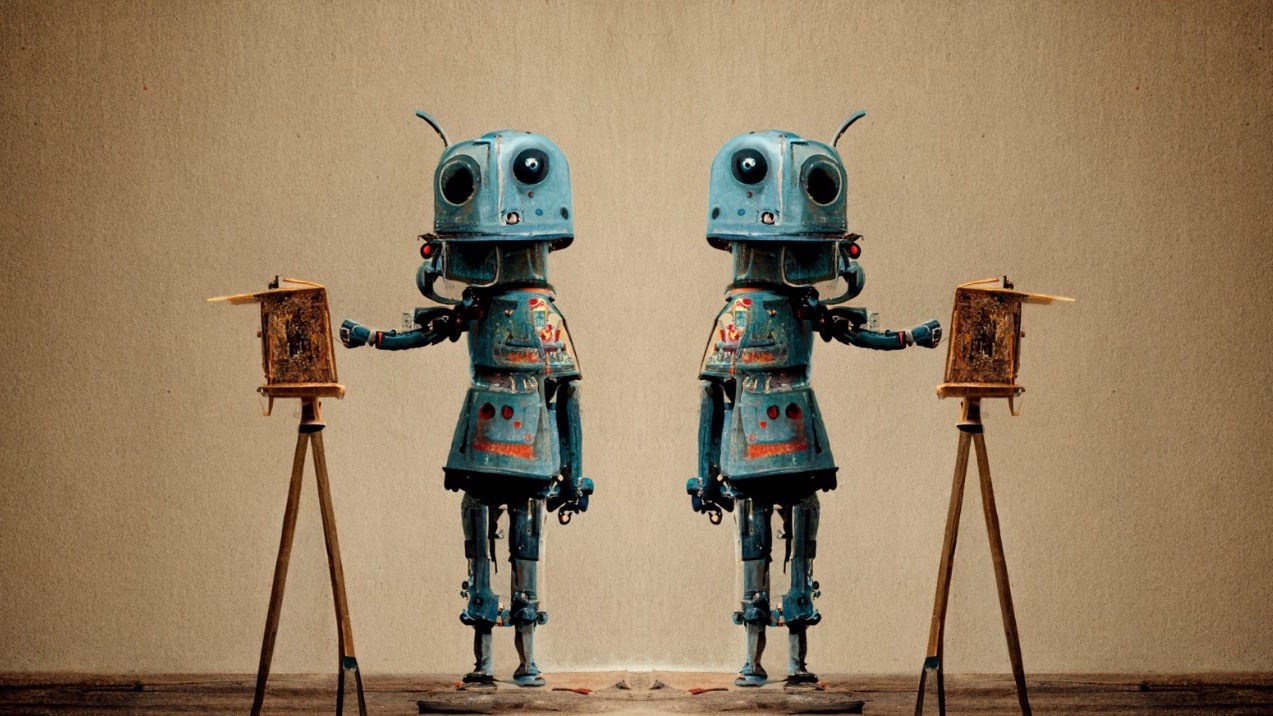

This begs the question: What makes original art so much more valuable than forged art? Plenty of aestheticians — scholars who study the nature and perception of beauty — have already tackled this question, yet none have done so as successfully as the legendary filmmaker Orson Welles, whose 1974 documentary F for Fake not only shows Elmyr de Hory at work, but also explores the elusive relationship between illusion, trickery, genius, and art.

Although de Hory was a wanted criminal, Welles does not present him as such. On the contrary, the artist we meet in F for Fake strikes us less like a crook and more like a kind of Robin Hood, someone who uses their skill and charisma to get the better of stuffy institutions that, in all honesty, could use a blow to their ego. De Hory comes across as witty, inventive, and life-affirming. Surely, he is cut from the same cloth as the creative geniuses whose copyright he’s infringing upon.

Redeeming the faker

Orson Welles not only respects de Hory, but identifies with him. Halfway into F for Fake, the documentary directs our attention to some of the hoaxes surrounding its own director. Welles’ showbiz career began when he, while traveling through England as a teen, convinced a theater troupe that he was a rising star on Broadway. His 1938 radio adaptation of War of the Worlds, meanwhile, led to nationwide panic when listeners failed to realize that the “news broadcast” about an alien invasion was purely fictional.

Aside from demonstrating that trickery can make great art, F for Fake also argues that originality and the value we attach to this concept are illusions in and of themselves. De Hory is far from the only artist who presents as authentic something that, in truth, is not. Welles points to Irving, the very same journalist who wrote a book about de Hory, who had previously confessed to inventing what readers thought was an autobiography by the mysterious and reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes.

The same principle can be applied to, say, Picasso. Though typically imagined as a genius painting in a creative vacuum, he was in fact heavily indebted to — and often stole from — other artists. This is not to say he was a thief, but that making art is a collaborative and assimilative process as opposed to an individualized one. Just as Orson Welles pasted together existing narratives to form F for Fake, so too did Elmyr de Hory — in forging works from other painters — create art that is entirely unique and, in many ways, just as valuable.