Science And Poetry Both Depend On Metaphors

1. Science, like poetry, depends on metaphors*. They can hide, sometimes causing mischief.

2. Science’s signature moves deploy two or more metaphors. Pythagoras’s “All things are number.” Plus at least one other, framing what the numbers mean (often tacitly, through tools or models).

3. Scientists should “think like poets and work like accountants,” E. O. Wilson advises. Useful number crunching builds on the poet’s rarer skill of making good metaphors.

4. Good metaphor-making can make geniuses: Energy conservation is like balancing account-books (Joule). Evolution’s “struggle for existence” is like humanity’s economic struggles (Darwin).

5. But bad metaphors can mislead entire fields: People ≠ biological billiard balls. Economies ≠ gases. (Alarmingly, “economic poet” Gary Beck metaphorized—>family = “little firm,” kids = “durable goods,” heroin = bowling.)

6. Let the “data do the talking” (preach Freakonomics folk)? Alfred Marshall noted that can be “treacherous.”

7. You can’t always count on Pythagoras’s number-world move. For example many concepts in biology, economics, and social science (e.g., fitness, utility, happiness) don’t have the mathematical properties of mass or length. They don’t fit a ratio scale and aren’t as measurable (=weakens the utility of math).

8. Many are confused about how quantitative and qualitative relate; e.g., Nate Silver says that those not “quantitatively inclined” risk creating “a lot of bullshit.”

9. But fruitful quantification requires sound qualitative distinctions, otherwise it risks increasing bullshit—>e.g., the average human has ~1 ovary + ~1 testicle. Mixed-types math can be fruitless (≠ apples-to-apples comparison).

10. Statistical methods are especially slippery number-world tools. They require that underlying phenomena have sufficiently stable representative patterns—valid for physical traits like height variation, but often not for behaviors (different kinds of variability).

11. Stats harbor new versions of old logic woes, like the fallacy of composition—projecting properties of parts onto wholes (e.g., apples are made of atoms, all atoms are invisible, therefore apples are invisible). And its opposite the fallacy of division (ascribes properties of wholes onto parts).

12. Consider data on shootings by police. Sendhil Mullainathan blunders in claiming that police racial bias has “little effect.” That’s a fallacy of division, assuming national data represent localities well. Conversely, Rajiv Sethi notes a statistical “fallacy of composition,” can stats from one city be of any use in any differently composed city?

13. Top researchers often mishandle stats, e.g. p-value cherry-picking (in medicine, economics, psychology), multiple regression (social sciences, randomized trials). And standard stats moves can’t always help. Randomization still drops the ball on average testicle counts, and more data doesn’t automatically overcome lumpiness (Mullainathan’s misstep).

14. Three distinct pattern types exist with intrinsically increasing levels of variability: see Newton vs. Darwin vs. Berlin patterns. And tools like statistics and algebraic equations yield more in physics than in social sciences.

15. For example, Diane Coyle calls the seemingly objective GDP a tarnished measure. It’s a badly built number, it doesn’t distinguish “bads” from genuine goods, and it omits all that isn’t sold (marry your housekeeper—>GDP declines).

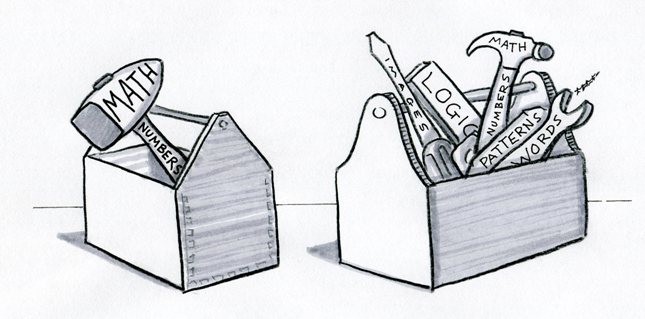

16. The cult of calculation and data is seductive. And I’m no quantiphobe. But number crunching has no monopoly on precision or truth. Words, metaphors, non-numerical logic, images, and patterns can be exact and can exceed what numbers can do.

17. A desire to jump to “the numbers” isn’t always wise. We often shouldn’t ignore unquantifiable factors, or the metaphoric or qualitative weaknesses hidden in the number-world mindset.

*—Deep conceptual metaphors structure most of our thinking (George Lakoff).

Illustration by Julia Suits, author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions, and The New Yorker cartoonist.