The origin of humans is not East Africa. It’s much broader.

In his song, “Africa Center of the World,” the great Nigerian musician and activist Fela Kuti sang, “We are no third world / we have been always first.” Kuti, who was arrested over 200 times for political agitation and created his own communal compound within Lagos, the Kalakuta Republic, championed African pride wherever his music, Afrobeat, brought him.

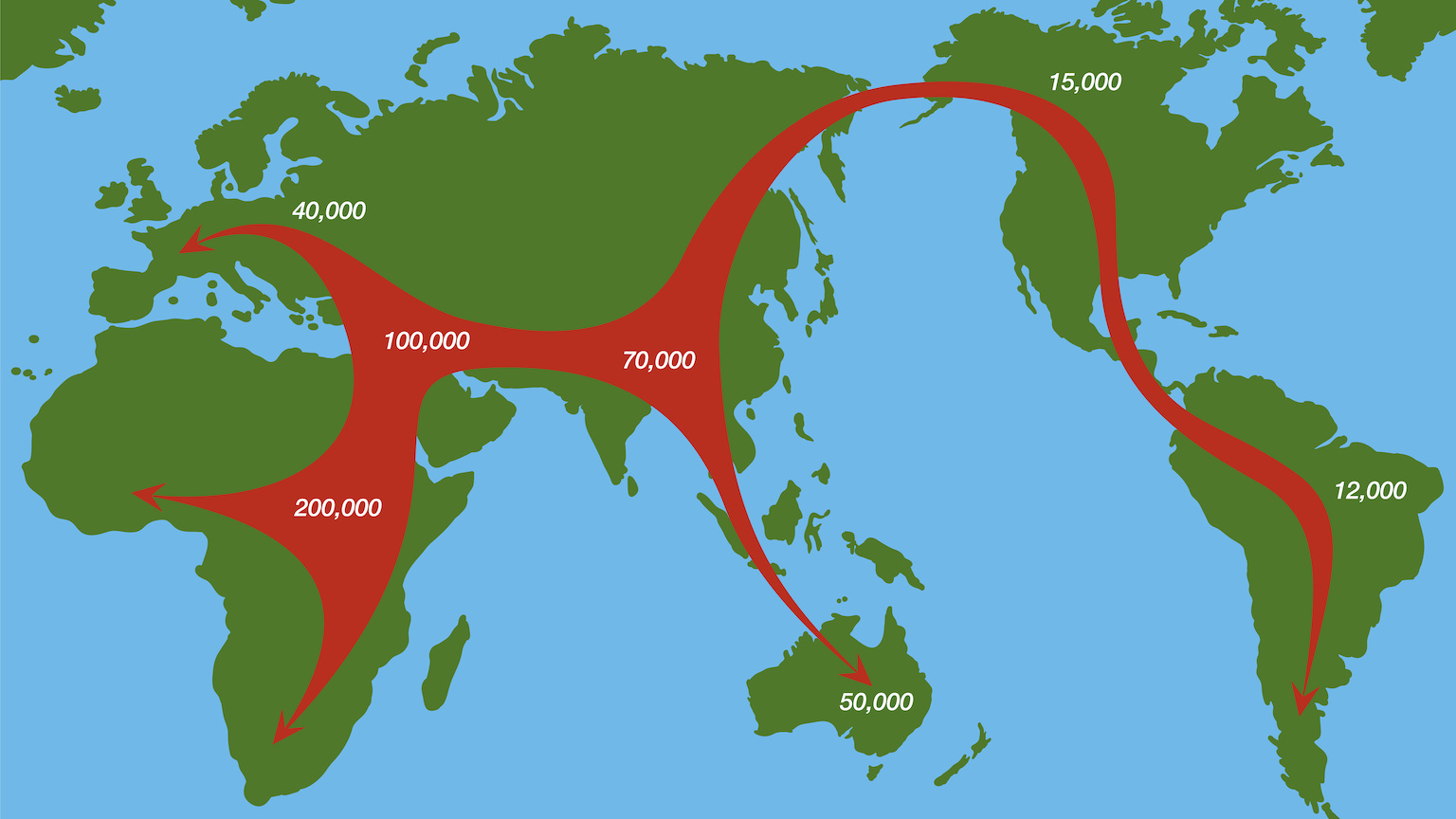

While it remains true that Africa holds the remains of the first members of our species, just where that location resides is under dispute. For decades archaeologists have pointed to East Africa, but recent research contests the single-origin theory:

This continental-wide view would help reconcile contradictory interpretations of early Homo sapiens fossils varying greatly in shape, scattered from South Africa (Florisbad) to Ethiopia (Omo Kibish) to Morocco (Jebel Irhoud).

While it might not sound like that much territory, we must remember the popular world map we grew up with in school is fabricated; Africa is larger than the entirety of North America. If judging by land mass, we should take Fela’s advice that it is the center of the planet. Here’s one perspective on its size:

The single-origin myth, as historian Yuval Noah Harari points out, has never been clear-cut. It’s not like there was a single generational gap between “Southern Apes” (Australopithecus) and Homo sapiens. Along the way, there was Homo neanderthalensis, which we all know about, as well as the East Asian Homo erectus, Homo soloensis in Indonesia, Homo floresiensis on the island of Flores, the Siberian Homo denisova, and two others in East Africa, Homo rudolfensis and Homo ergaster. The Guardian article linked to above cites another two (Homo naledi and Homo heidelbergensis) co-existing with our forebears in Africa just over 200,000 years ago. What happened to all of these genetically unique cousins? Well, as Harari notes, we likely killed them.

And so the cradle of civilization is more like a caravan. The paper, published in the journal, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, suspects that humans as we know them evolved independently across the continent at different times, divided by ecological boundaries that would have made it rare that they ever chanced upon the others.

Rare, but not impossible. Contact with other civilizations was fluid, marked by long gaps. These groups were likely to come upon one another when the climate allowed, though they then dispersed again, notes the paper’s lead researcher, Dr. Eleanor Scerri, an archaeologist at Oxford University:

These barriers created migration and contact opportunities for groups that may previously have been separated, and later fluctuation might have meant populations that mixed for a short while became isolated again.

The researchers used a multidisciplinary approach to this study because, as they write, evolution is complex. Stumbling upon one human skull that happens to be older than another doesn’t necessarily mean the oldest wins bragging rights for an origin myth. This means that the rise of culture, one of our unique traits among the animals, could also have been dispersed and risen independently, which forces us to confront interesting questions about the onset of our particular brand of consciousness.

As Harari writes, we likely created the single-origin myth both out of convenience and to hide the violence inherent in our ancestral past. What history or biology teacher wants to tell their students that we won the battle of the species not by domesticating cattle and dogs and implementing widespread agriculture, but by murdering, interbreeding, and likely eating those closest to us?

History is never that easy a discipline. This fascinating new research will help us to rewrite archeology, anthropology, and evolutionary biology books once again. Still, the researchers haven’t proven Fela wrong. He knew who was first.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Facebook and Twitter.