Status Anxiety: A Social Scientist’s View of the Art World

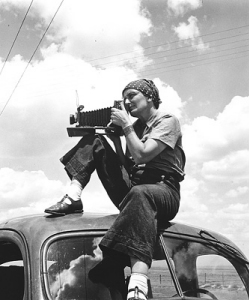

In a recent article in The Australian, Matthew Westwood writes about Canadian social scientist Sarah Thornton, whose book Seven Days in the Art World (cover above) “explores the dynamics of creativity, taste, judgment, status, money, and the search for beauty in life.” In other words, this social scientist argues that contemporary art is not a science, and that judging great art and great artists has always been a cutthroat business in which status rather than talent often reigns supreme. It’s easy to understand these concepts when discussing contemporary art, where status is as freshly bestowed and easily wiped clear as wet paint. But Thornton’s thesis holds value even for the hallowed halls of art history.

“Artists like to give the impression of being egalitarian,” Westwood writes, “but Thornton says they are as obsessed with status as anybody.” Status anxiety stretches back as far as the Ancient Greeks and Romans, who vied among themselves for the title of greatest artist in pseudo-Olympics that crowned winners who would receive the greatest share of patronage. In the Renaissance, powerful rulers lusted for a house artist to glorify them for the ages. Pope Julius II kept both Raphael and Michelangelo close at hand. Michelangelo not only painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for Julius, but also designed “the Warrior Pope’s” sculpture-festooned tomb. Despite their protestations and frequent personality clashes with His Holiness, both Raphael and Michelangelo enjoyed the perks of being the Pope’s house artists and never suffered from the status anxiety that lesser artists, with lesser patrons, felt keenly.

Thornton focuses on the fleeting nature of fame, citing Julian Schnabel as an example of how a darling of the 1980s art world is virtually dead in the twenty-first century (although he continues to make interesting films). Even Andy Warhol languished in relative obscurity until the MoMA bought 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans in 1996, according to Thornton. It wasn’t until “nine years after his death, that [Warhol] really came into his own,” she argues. I’d argue against the idea that Warhol stood as a non-entity during his lifetime considering how long he stretched his 15 minutes of fame (a phrase he coined), but I think Thornton’s point is still valuable.

Big reputations can suck the air out of a room, or even an era of art. Hans Makart dominated late nineteenth century Viennese art. Only specialists know that name today. Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier hogged so much of the Paris Salon mojo that Manet and the Impressionists had to rebel as a last resort just to find a place in the sun. Ross King’s The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism gives the full measure of the Meissonier—Manet matchup, but the ending is given away before the book even begins. We know that Manet et al., the “good guys,” will win in the end. Our hindsight dulls the razor’s edge suspense of the status anxiety they faced and fought against. But Meissonier, as King points out and Thornton would most likely agree with, isn’t a “bad guy” at all. He only wanted what Manet wanted. His only “crime” in our eyes was actually having it. Who today will be the Meissonier of today, unknowingly holding back the progress of art history by being the most popular artist of his time? If I were a betting man, I’d place a wager on Damien Hirst, but that seems like too safe a bet given his already fading starlight in the art world firmament.

So, the next time you wander through a museum, consider the vagaries of fame. Van Gogh died a broken man only to become a posthumous myth first in Germany, which adopted his strangeness of mind first, even before Vincent’s adopted and native lands. So few confirmed Vermeers exist mainly because the eighteenth century essentially forgot him, and the nineteenth century discovered him too late to do much about saving him. Two “givens” such as Van Gogh and Vermeer were once “nobodies,” just a blink away from permanent oblivion. Prestige too often trumps talent for us to naively believe that at least some great artists have slipped away for good. The status anxiety I feel is the anxiousness over those lost artists, who lacked nothing but the right connections, the right timing, and, most sadly, the right, sympathetic audience.