Mistaken Identity

How do you tell a Rembrandt from a non-Rembrandt? Even the experts have been stumped, and they’ve been stumped for centuries since Rembrandt himself passed away. Drawings by Rembrandt and His Pupils: Telling the Difference, an exhibition at The J. Paul Getty Museum through February 28, 2010, tries to untangle the web of confusion spun in many ways by the very teaching practices Rembrandt himself used when passing on his wisdom to the next generation of artists.

Rembrandt opened up his atelier to students beginning in the late 1620s and continued to do so until his death in 1669. We know of fifty pupils from those four decades, but certainly many more have been lost to history. Rembrandt followed the standard curriculum for art studies of the time for the most part—copying from casts of classical statues, drawing from live models, and even excursions outside the studio to draw from nature. Thanks to the standards of the time and Rembrandt’s forceful personality and drawing technique, these students often mastered a Rembrandt-esque style. “Imatatio was not considered a sign of insufficient imagination,” Holm Bevers explains in his essay from the exhibition catalogue, “but was rather seen as proof of an artist’s comprehensive knowledge and acculturation. Artists were expected to compete with famous predecessors and to attempt to surpass them.” Rembrandt himself copied Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper as a student, measuring his developing skills against those of giants from the past.

Some pupils who perfected the Rembrandt-esque style best became the master’s assistants, often to make copies of real Rembrandt paintings for additional sales. Rembrandt kept many student drawings as instructional materials, often setting them into albums alongside his own works. And so began the confusion. When Rembrandt died in 1669, he left behind only twenty drawings bearing his signature. Those albums of his and his pupils’ drawings were found and all labeled “Rembrandt” when put up for sale. The subsequent deaths of pupils and the discovery of their unsigned Rembrandt-esque drawings, which were also labeled as “Rembrants” for the marketplace, added to the confusion. Today, several thousand Rembrandt/Rembrandt-esque drawings survive from the seventeenth century. This exhibition traces the long struggle to separate master from student work while also showing just how Rembrandt not only taught his students but also the special qualities that remained beyond their reach.

As Peter Schatborn and William W. Robinson relate in their catalogue essay, the idea of art connoisseurship begins with this Rembrandt puzzle in the eighteenth century. The long-held approach to judging a genuine Rembrandt, aside from trusting the expert’s eye, was to take the work in question, compare it to the few signed works by Rembrandt or those directly connected to his paintings or prints and look for similarities both in technique and style. Modern scholars have delved even more deeply by studying the works of Rembrandt’s known pupils, including Samuel van Hoogstraten, Nicolaes Maes, Willem Drost, Carel Fabritius, and Ferdinand Bol. Rembrandt remains the star of the show, but this exhibition shines a light on the talents of many artists known mostly to specialists.

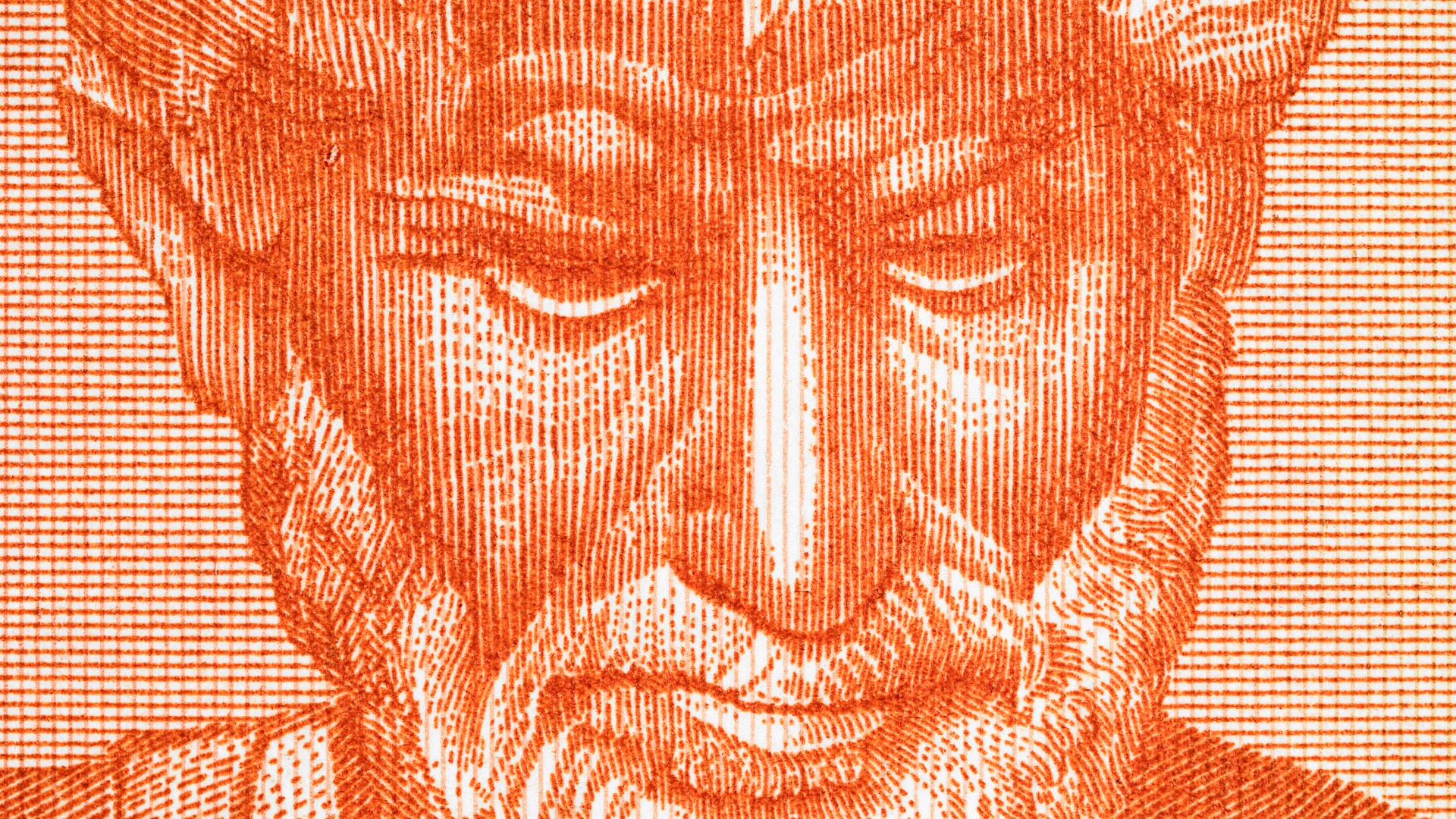

In this show, drawings by Rembrandt are placed side-by-side with similar works by students. The resemblances can be uncanny, but the differences are there for those who look closely enough. Some differences are clear, such as the same model drawn from a different angle as Rembrandt and the student worked simultaneously from different parts of the room. Other differences take a sharper eye, such as versions of Christ as a Gardener Appearing to Mary Magdalene by Rembrandt (pictured) and Ferdinand Bol. The scene alludes to a passage in John 20:8-18 right after the Resurrection when Mary Magdalene mistakes the risen Christ for a simple gardener. When Christ corrects the mistaken identity, Mary reaches out to touch him. “Noli me tangere,” Christ responds as he recoils, “Do not touch me.” Similarly, Bol cannot touch the special qualities Rembrandt brings to the scene. In Rembrandt’s version, Christ’s “taut profile, the hand gesturing as he speaks, and the precise placement of the feet” all “lend Christ an imposing presence” versus the “nonchalant pose” in Bol’s version, Schatborn writes. Of course, Rembrandt encouraged his students to create variations on his themes and not slavishly copy him, but they often fell short of that spark of divinity Rembrandt could call upon in his art. You can teach technique, but you can’t teach talent, is the overarching theme of the show.

Rembrandt had a distinct advantage as the teacher, but even his best students never managed to close the gap. Few ever have. After viewing Drawings by Rembrandt and His Pupils: Telling the Difference you may still not be able to tell the difference yourself, but you will come away with a greater appreciation of just how different, and great, Rembrandt remains.

[Image: Rembrandt, Dutch, 1606–1669. Christ as a Gardener Appearing to Mary Magdalene, about 1640. Pen and brown ink, corrections with white gouache, indented for transfer. 15.4 x 14.6 cm (6 1/16 x 5 3/4 in.) Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. De Bruijn–Van der Leeuw, 1949; EX.2009.1.62. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum.]

[Many thanks to The J. Paul Getty Museum for providing me with the image above and a review copy of the catalogue Drawings by Rembrandt and His Pupils: Telling the Difference.]