Lucky We Don’t Have To Worry About Demons! (Or Do We?)

Historically, most people have worried a lot about demons. In fact, while we are accustomed to think of pre-modern history as an age characterized by belief in God, it may be more apt to think of it as an age characterized by fear of demons. Though people from different times and places obviously differ in a variety of ways, in general people who are not “modern” spend a great deal of time plotting against, warding off, looking out for demons. Modern people like us are spared this cumbersome waste of time and mental energy.

Or are we?

In what follows, I will explore the idea that many modern people – people “like us” – are still encumbered by anxiety about demons. If this is true, what does it say about the implicit assumption that “modernization” necessarily brings “secularization”? And what should we do about the demons?

First, let me try to describe how I imagine the preoccupation with demons in pre-modern life. My description may look most like pre-modern Jewish demonology, since it is Jewish anxiety about “liliths” and other demons that I am most familiar with. But I will mix in other elements as well.

The battle starts at home. You will need a heavy battery of amulets, especially on doorposts and hanging above your children’s beds.

Your body must also be protected. Bracelets with protective charms may be helpful, or a necklace. You might sew parchment with an anti-demon incantation written on it into your shirt.

After praising or speaking fondly of another person be sure to add: “stay away demons!” “No evil eye!” You will also want to steer clear of any place, object, or person that is known to have come into contact with a demon.

This last point is crucial. It is best not to think of demons as individuals. Some may be individuals: you may have a picture in your mind of a red-skinned, horned devil who carries a pitchfork, for instance. But often demons are more like “forces” or “powers.” They are above all contaminating forces that pollute whatever they touch. They are nasty and pervasive contagions that inherently transmit the taint of danger. Demons are impurity, menace, evil personified.

In many societies today, modern and otherwise, certain kinds of people are treated as demons: gays and lesbians, transvestites and transsexuals, blacks, Jews, women, albinos, Muslims, people with physical and mental impairments, poor people, foreigners, overweight people, and many other kinds of people.

Social scientists describe such people as carrying a “stigma.” But I want to play with the idea that “stigma” is just a quintessentially modern reductionistic way of describing the demonic.

If this is so, then it seems most appropriate for us to take a “phenomenological” approach to demonology. That is, we should focus on the fear, disgust, and defenses of those who are haunted by demons, rather than on the demonic per se, or the demonic-in-itself.

Clearly, there is no agreement about who or what are the real demons in our world. I am Jewish and I don’t think of myself as a demon. “Foreigners” is an entirely relative term, and yet foreigners often provoke fear, disgust, and elaborate protective measures meant to avoid contamination. On the other hand, rats are obviously beady-eyed, fury, (a shiver is literally going through my body as I write this), horrible demons, right?

BUT, you might be thinking, there is a big difference between the way modern stigmatizers relate to the stigmatized and the way medieval people related to demons. After all, pre-moderns literally believed in supernatural forces.

Is this right?

I’m not so sure. The pre-modern world, where vigilance against demons was a regular part of everyday life, did not include the natural/supernatural dichotomy that we take for granted. Demons were not “supernatural” forces to be distinguished from “natural” forces like gravity.

In fact, it is worth recalling what John Maynard Keynes once wrote about Isaac Newton [1643-1727], who is often credited with inciting our mechanistic, disenchanted world: “Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind which looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than 10,000 years ago.” Newton’s thinking about gravity did not impede his thinking about alchemy, apocalypse, and other occult matters.

Pre-moderns did not “believe in” demons, so much as they hid from them and fought them. There was an implicit belief involved, of course. But the questions at hand were practical (“how do we defend ourselves?”), not epistemological (“how do we know that demons actually exist?”).

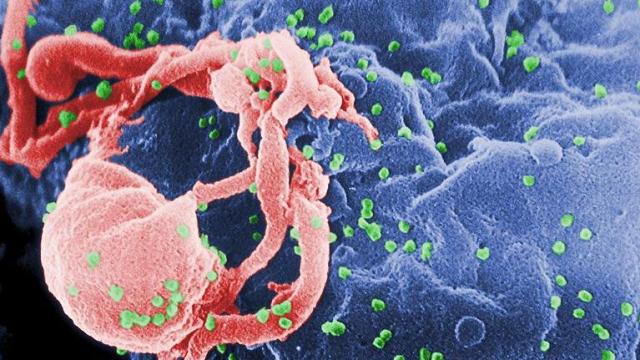

Similarly, most of us fear diseases and take precautions in order to avoid catching them. It would be weird to talk about this by saying: “people like us believe in diseases.” It’s true. We do assume that diseases exist, even though few of us have the training in biology and pathology to explain what diseases actually are. Overwhelmingly, though, our way of relating to disease is practical, not epistemological.

Plenty of people today relate to others practically as demons. When a demon is near we stiffen and become cautious. They are gross, disgusting – “I don’t have anything against them, I just don’t want them anywhere near me.” We don’t let them near our children. We don’t go into their neighborhoods. We don’t want them to touch our food. We don’t want them to marry into our families.

If modernization entails secularization, and secularization entails “disenchantment,” and disenchantment means that people no longer live in fear of demons, then perhaps we are not quite as “modern” as we think we are. Or, maybe, the words “modern” and “secular” are merely ways of describing, among other things, a transformation but not a debunking of the demonic.

This would be unfortunate from a moral point of view: no person deserves to be treated like a demon.

But maybe we can take solace from a surprising source. Notice that the horror genre is a staple of popular entertainment precisely at a time when vampires, zombies, and other monsters are not generally feared in everyday life (we generally assume that they do not actually exist).

Horror fiction is a way of confronting what is “unnatural” and “frightening” that is ultimately playful. Comedy also allows us to confront playfully what might otherwise induce anxiety.* Maybe the popularity of comedy that plays with stereotypes and stigma – think of the stand-up comedy of Sarah Silverman, or perhaps even the television show Glee – indicates that the demonization of “kinds of people” is losing plausibility.

If so, I wonder where the newer demons now lurk.

*I was introduced to the idea that horror and comedy might share something in common reading the work of philosopher Noël Carroll. I have not represented his view here. See: Noël Carroll, “Horror and Humor,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 57, No. 2, Aesthetics and Popular Culture (Spring, 1999), 145-160.