Junk Man: Revolution, Complicity, and Art

In Death of the Liberal Class, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Chris Hedges argues that liberals have “conceded too much to the power elite.” In other words, traditional liberal institutions such as education, religion, labor, and the arts have stopped challenging corporate powers and, instead, joined them. It’s a powerful and often depressing argument, especially when Hedges probes fields usually condemned for their “liberal” and “revolutionary” tendencies, such as art. Hedges raises the old question of what is art in a different way, asking if art is creative expressions that free the mind, what do we call creative works that support the status quo? Junk, Hedges would most likely answer, giving some surprising examples of famous “junk men” in American art.

Hedges juxtaposes two exhibitions he saw at the MoMA—the 2009-2010 special exhibition Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity and the museum’s permanent collection of American post-war art. Whereas the German Bauhaus pieces embodied “an artistic movement that was… integrated into social democracy and sought to eradicate the barriers between craftspeople and artists,” Hedges writes, the American art was “a dreary example of flat, sterile, and self-referential junk.” Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism—the three main movements of American Art in the second half of the 20th century—all served as apolitical eye candy feeding the interests of the rich.

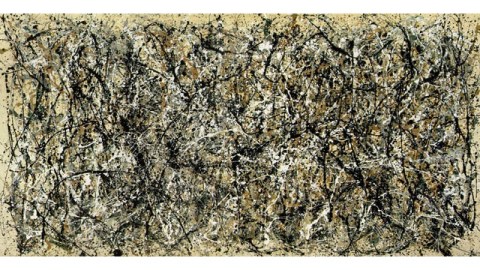

Although he began with revolutionary ideals, Jackson Pollock began painting “for the man” when works such as One: Number 31, 1950 (from 1950; shown above) started raking in the dough. “Museums and their arrogant curators appointed themselves as the arbiters of high culture,” Hedges accuses in his typical pull-no-punches style. “These liberal institutions ruthlessly filtered out artistic expression that confronted or exposed the darker side of the power elite.” Mesmerized by the trappings of success, Pollock (and Andy Warhol and the Minimalists after him) bought into the hedonistic, feel-good culture that Hedges claims serves as the opiate of the masses dealt by the powerful to keep the powerless in line. Pollock converted from antagonism to complicity faster than the car he drove to his fatal end.

What made Hedges argument ring even louder in my head was the revolution circling the globe right now. If democracy comes to those countries, can capitalism and corporate control be far behind? Artists in these countries are capturing the revolutionary spirit in their chosen medium, but will that spirit be squashed when those artists hit the big time? Now that the Jasmine Revolution seems to have reached China, will artists such as Ai Weiwei stand with the rebels or the power? Ai once went into exile for his actions, but more recently acted as consultant on the Beijing National Stadium (aka, the “Bird’s Nest”) for the 2008 Olympics, the Chinese government’s public relations push for the 21st century. The Political Pop and Cynical Realism movements in contemporary Chinese art have taken previously apolitical genres and made them politically relevant. But will Yue Minjun—painter of the famous smiling faces masking the pain of anonymity under government repression—be smiling for a different reason once fame and fortune take hold? It remains to be seen if these artists can remain revolutionaries once the establishment embraces them. The Faustian bargain taken by Pollock and others will be offered again and again, with the ultimate price being the social value of the art itself.