How World War I Changed Pablo Picasso

As a citizen of neutral Spain, artist Pablo Picasso didn’t fight in World War I. He did, however, watch his French friends go off to war and spent the war years in Paris. Already a prominent modernist artist, Picasso stood outside of mainstream society, but couldn’t escape the influence of his adopted country torn by war. How World War I changed Pablo Picasso and his art is the subject of the exhibition Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change, which runs at the Barnes Foundation through May 9, 2016. Even for an artist who continually shifted styles, Picasso’s Great War experience radically changed him and pointed the way to everything that followed.

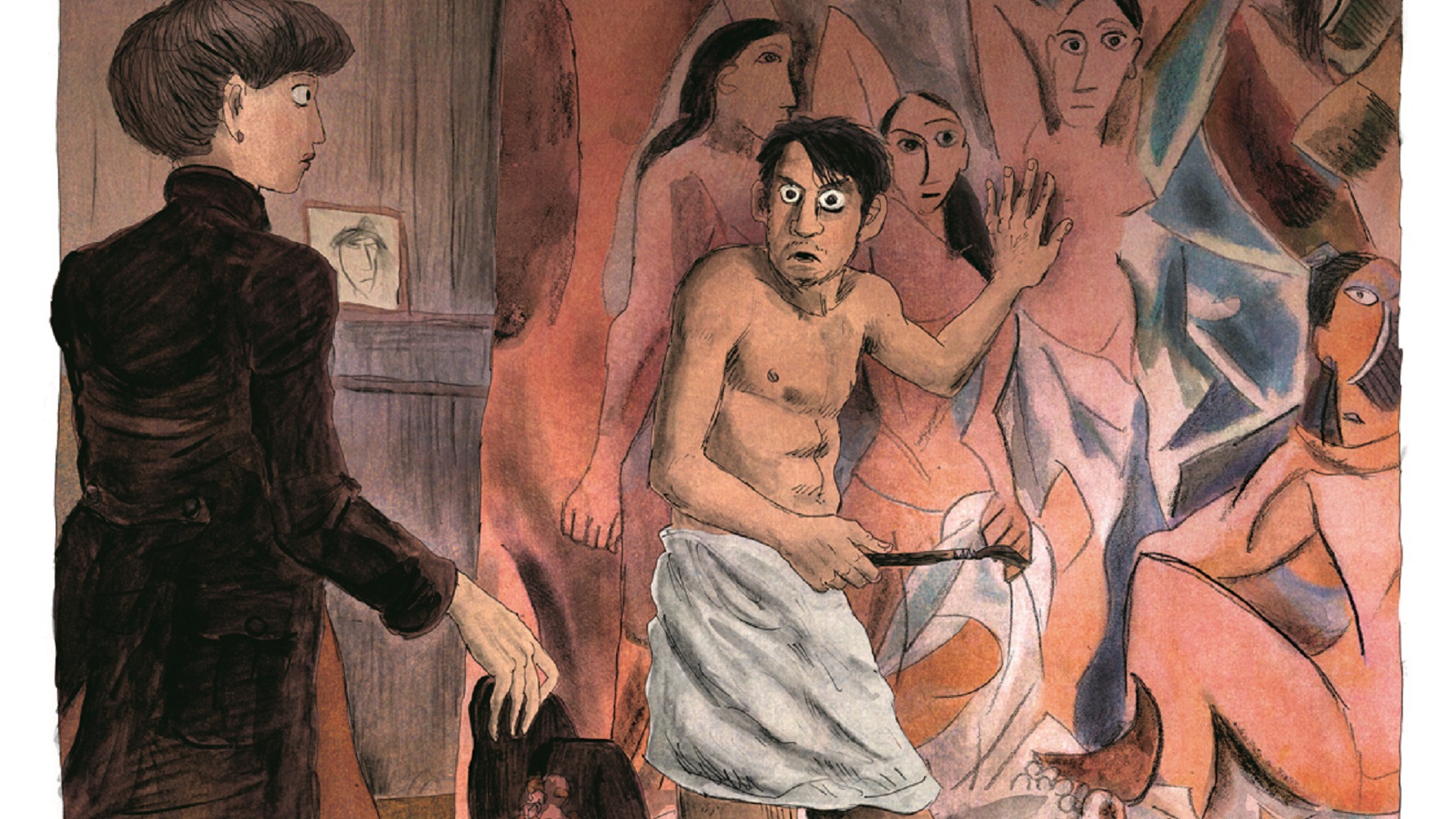

When the geopolitical dominoes fell after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, Picasso’s name was synonymous with modern art, specifically Cubism. Works such as Still Life with Compote and Glass (shown above) not only proved Picasso’s Cubist bona fides, but also demonstrated his continual experimentation, as seen in the almost pointillist dots on the playing cards in the painting. Ever resistant to labels, Picasso continually pushed the envelope creatively, experimenting his way from one style to the next. Picasso’s push accelerated as the Parisian homefront around him began associating Cubism and other modern movements with the enemy. “Disparagingly referred to as ‘bôche,’ Cubism was identified with the German enemy and perceived as unpatriotic,” curator Simonetta Fraquelli writes in the catalogue. (A short film in the gallery wonderfully captures the wartime hysteria that swept Cubism up in its wake.) Even if he never saw the battlefield, Picasso still needed to battle misperceptions of his art.

Picasso, the arch-modernist, therefore shocked fellow artists in 1914 with a naturalistic, neo-classically French drawing of his friend Max Jacob, one of his few French friends not pulled away by the war. How could you make Cubist and naturalistic images at the same time? Drawings such as that by Picasso of his future wife Olga (shown above) felt like a slap in the face of modern art, a turning back of the aesthetic clock. Rather than a “repudiation,” however, Fraquelli argues that “the two artistic styles—Cubism and Neoclassicism—are not antithetical; on the contrary, each informs the other,” sometimes even happening simultaneously in some works by Picasso.

Such radical coexistence appears in Picasso’s Studies (shown above), in which Cubism and Neoclassicism appear literally on the same canvas, compartmentalized for the moment, but standing in fascinating juxtaposition to one another. Picasso frames miniature cubist still lifes about a realistic woman’s head, hands, and a couple dancing on the beach. Despite the visual boundaries, the styles spill out onto one another—the Cubism verging closer on naturalism while the naturalism metamorphosizes into something almost inhuman in its monumentality. “Picasso was intent on defining a strategy by which he could retain the compositional structure of Cubism while introducing elements of naturalistic representation,” Fraquelli believes. Whenever anyone wanted to label Picasso as a Cubist, a Neoclassicist, a Patriot, or a Traitor, he looked for a new way out.

To look forward, Picasso looked back—both far back and more recently. The great magpie of modern art, Picasso turned his long-time love of the Neoclassical Ingres and blended it with his newfound respect for the more recent work of Renoir. Possibly another portrait of Olga, Seated Woman (shown above) takes elements of Ingres’ classical mode and grafts them onto the joyous fleshiness of Renoir. As the exhibition points out, many see post-war works such as Seated Woman as a calming call for a “return to order,” but the catalogue chooses to echo critic T.J. Clark’s view of Seated Woman as “the best means [Picasso] has, in 1920, to make the body materialize again” after the disintegrating forces of Cubism (and, possibly, the war).

Pivotal moments in Picasso’s wartime development, personal life, and the exhibition all center on his involvement in the ballet Parade. A room full of candid snapshots recreates the fun-filled day of August 12, 1916 when Jean Cocteau, on leave from driving a Red Cross ambulance for France, asked Picasso to design sets and costumes for a ballet starring Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company dancing to poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s libretto and Erik Satie’s music. “Much of the energy generated by [Parade] derived from the way Picasso played Cubist elements against figurative ones, especially the contrast between the lyrical classicism of the safety curtain and the violent modernism of the set behind,” Fraquelli writes. Picasso’s Cubist costumes, including that for the Chinese Conjuror (shown above), literally brought Cubism to figurative life on the stage. Seeing recreations of the giant costumes loom over you and watching performances of Parade in the exhibition, you get a sense of the collaborative energy of the piece and Picasso’s desire to get involved.

Parade rejuvenated not only Picasso’s search for stylistic resolution, but also his love life when he met (and later married) ballerina Olga Khokhlova (shown above). In his catalogue essay, Kenneth E. Silver credits Cocteau as “a specialist in binaries like these [found in Parade], and of invoking and unhinging them in especially provocative ways.” Picasso found Parade provocative in a good way, but the public, unfortunately, generally didn’t. Cocteau’s dream of uniting the old form of ballet with the new forms of modern art failed to appeal to a public, Fraquelli suggests, “long[ing] for the escapist entertainment of classical dance, not a foray into contemporary life and popular culture.” Accounts of the uproar vary, but in the worst, only Apollinaire, in uniform and sporting a bandaged head wound, could save the angry mob from throttling the cast and crew. Parade’s failure illustrates the mood of the time as well as the high stakes of the stylistic games Picasso was playing.

Picasso continued to oscillate between styles, not schizophrenically, but in a single-minded search to expand his horizons while escape all boundaries. The exhibition offers the 1918 Pierrot (shown above, left) and the 1924 Harlequin Musician (shown above, right) as perfect examples of Picasso’s ability to shift gears and consolidate approaches continually. The only constant is Picasso’s constant searching for a new method, a new approach to representing the world and the people in it. Pierrot is more realistic, but his sadness “recalls the unsettling and enigmatic ‘realism’ of Giorgio de Chirico’s early metaphysical paintings,” Fraquelli points out. On the other hand, the allegedly cold, analytical Cubist Harlequin explodes with color and joy, perhaps the realistic picture of a man deliriously in love. Picasso forces us to ask which is the more “real” picture.

What is the “real” picture of Picasso? Is it the postwar self-portrait he drew (shown above), mingling Neoclassical realism with the strong line he would go on to simplify into stirringly childlike power to touch the emotions? Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change fills in more details of the “real” picture of Picasso, especially for those who know him best as the creator of Guernica, the most powerful artistic peace statement of whole war-torn 20th century. Just as the First served as a prelude and catalyst for the Second World War, Picasso’s artistic response to World War I shaped and inspired much of his response to World War II, when his native Spain lost its neutrality and joined in the carnage. A small but tightly focused show, Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change argues by the end that all Picasso wanted was freedom from all ideologies, all dogmas, all limiting labels—the freedom to be and to find out what being entails, a freedom critics and wars so often curtail.