How I Met Your Mother

I can’t think of any artist who suffered as much in his life as Arshile Gorky. Fleeing the ethnic cleansing of Armenians by Turkish troops, he watched his mother starve to death in 1919 surrounded by fellow refugees. Upon coming to America, he shed his birth name of Vosdanig Adoian and remade himself as Arshile Gorky, taking the same last name as his hero, the Russian writer Maxim Gorky, who had supported the Armenian cause.

After years of success as an artist, the stretch from 1946 through 1948 became a sheer hell—a studio fire, rectal cancer, his wife’s infidelity, a car accident resulting in a broken neck and paralyzed painting arm—ceased only by his suicide. The Tate Modern’s exhibition Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective brings the pain, of course, but also the triumph of a man who never truly left his mother country while bringing modernism to his new one.

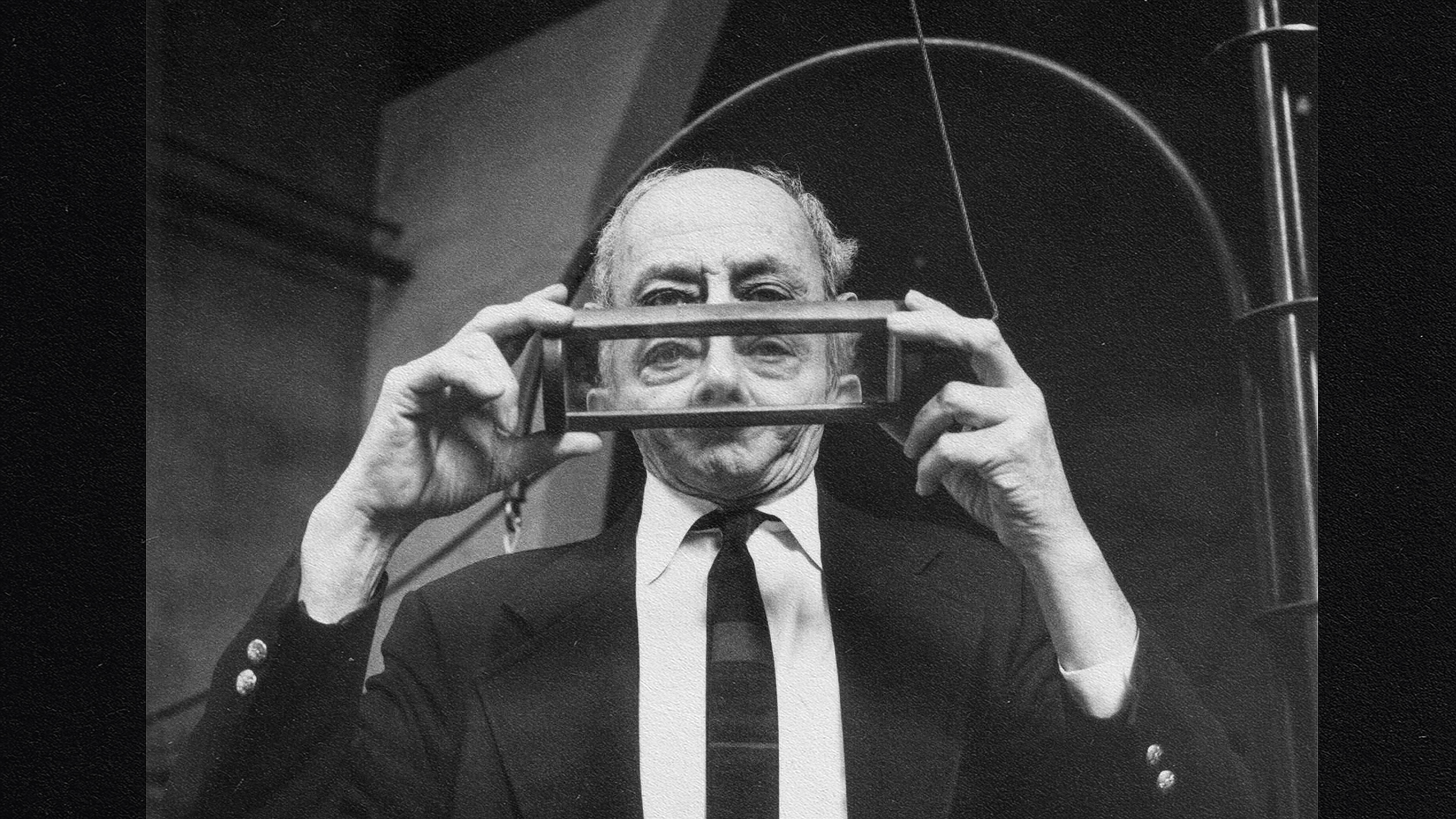

Gorky’s The Artist and His Mother seems an odd choice at first glance for a retrospective of an artist known best for his proto-Abstract Expressionist and –Surrealist work. But, as Kim Servart Theriault writes in the masterful catalogue, “Gorky’s predicament as an immigrant and the trajectory of his development as an artist were quintessentially modern and indicative of an American experience that critics such as Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg would codify in the 1950s.” The magpie of modernism, Gorky took a little bit from everyone, including Picasso, whose classical phase influenced Gorky’s resurrection of his mother in paint. Working from a cherished photograph of himself and his mother before their travails, Gorky made a realistic work in a modernist vein. As Jody Patterson writes in her essay, “[M]odernist strategies were deemed to be the only ones appropriate to a realist engagement with the contemporary world.” When you live in a world of unreasoning cruelty, Surrealism and other modern “isms” seem the logical choice.

In the context of “New Deal” WPA murals Gorky painted in 1935 through 1937, Patterson sees a much more politically engaged Gorky than previously suspected. “Within a public and highly visible federal commission,” Patterson believes, Gorky “managed to execute a cycle of murals that engaged modernist forms in a sophisticated reconception of realism, while also, albeit subtly, expressing his solidarity with fellow artists on the left.” Still leery of political pogroms, Gorky kept his politics on the down low while paradoxically painting them on a large scale—hidden in plain sight. The apolitical artist of the past gives way in this exhibition to a passionate prophet railing against injustice, but quietly.

Gorky, however, never allowed politics to overpower his passion for art. “[T]hrough a patient and sustained study of the history of art through reproductions in magazines and books and repeated trips to museums and galleries in New York and other East Coast Cities,” writes Michael R. Taylor, Gorky “voraciously absorbed the techniques of the painters he discovered,” perhaps foremost among them, Cezanne. At the Cezanne and Beyond exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art last year, Taylor counted Gorky among Cezanne’s children, calling Gorky’s works in the exhibition an amuse bouche for this retrospective, which appeared at the PMA before the Tate Modern. Just as Gorky feasted at the buffet of art history, visitors to the exhibition can sample from the bounty of styles Gorky tasted and digested before moving on to the next thing that caught his eye.

Gorky the insatiable student evolved into Gorky the mesmerizing teacher. Gorky’s “encyclopedic understanding of the history of Western painting, from Paolo Uccello to Cezanne,” Taylor writes, “far surpassed that of his better-educated peers in the fledgling American avant-garde.” At the New School of Design, Gorky counted Mark Rothko among his students, but countless other artists took from Gorky’s storehouse of knowledge to find their own way. This retrospective proves that Arshile Gorky still has much left to teach us about the uses of modernism. Sadly, ethnic cleansing remains alive and well in our day, a century after Gorky lost his mother to Turkish cruelty. Gorky’s art reminds us of that tragic past and continues to point towards a future free of the madness that makes surrealism seem sane.

[Image: Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, 1926-36, 152.4 x 127 cm. Oil on canvas. Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, USA). © Arshile Gorky Estate.]

[Many thanks to Yale University Press for providing me with a review copy of the catalogue to and to the Tate Modern for the image above from the exhibition, Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, running until May 9, 2010.]