God Complex: How Rubens Flipped the Script on Michelangelo

It all started with a happy accident. Coming back to his office one day, curator Christopher Atkins looked at the catalog on his desk upside-down. On the cover was Peter Paul Rubens’ Prometheus Bound, one of the most important Baroque paintings in America. Atkins noticed that, upside down, Rubens’ Prometheus bore a distinct resemblance to Christ in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment (shown side by side above). The more he looked, the more similarities he found. The resulting exhibition, The Wrath of the Gods: Masterpieces by Rubens, Michelangelo, and Titian, examines how Rubens synthesized the imagery and styles not just of Michelangelo and Titian, but also of multiple sources from Northern European art to shape his own distinctive portrayal of gods and the god-like act of creativity. Rubens flipped the script on Michelangelo and turned a new page in art that today’s artists continue to emulate.

Any art argument delving into influences quickly turns into a detective story. The Wrath of the Gods gathers all the key witnesses (except for Michelangelo’s immovable fresco, of course) in one place for the first time ever. Atkins builds a strong visual case by listing the similarities between Rubens’ Prometheus and Michelangelo’s Christ: similar muscular builds, similar titanic scale, similar raised hands, and similar facial hair (Prometheus’ slight scruff versus Michelangelo’s unusually shaven Jesus). For Atkins, the “smoking gun” that breaks the case open are the similarly shaped slits indicating Prometheus’ daily torture and the spear wound from Christ’s Passion on the Cross. Most artists depict the eagle ripping Prometheus’ ever-regenerating liver from a much larger chest wound. For Atkins, Rubens’ choice in wound shape and size indicates that he had Michelangelo’s Christ on his mind.

1532. Michelangelo Buonarroti (Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015). Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Another “smoking gun” of the exhibition’s argument is Michelangelo’s Tityus drawing (shown above). We know that Rubens studied and sketched The Last Judgment while in Rome, but Michelangelo’s drawing of Tityus was also famous by that time thanks to prints and praise by Giorgio vasari in his Lives of the Painters. What Rubens most likely did not know was what appeared on the other side of the drawing. Michelangelo flipped the page and repurposed Tityus’ sprawling pose into the standing pose he used for Christ in The Last Judgment, thus proving that even Michelangelo connected the two figures in his mind. (The exhibition presents this drawing in the round, so you can walk around and see how Michelangelo traced the new figure through the paper.) But whereas Zeus punished Prometheus for giving fire to humanity, he punished Tityus for rape. Amazingly, Michelangelo converted a sinner into the ultimate saint. Typology — the idea that similarities between gods and religious figures connects them in a complex, meaningful way — already existed in Rubens’ time, but Rubens’ riffing off of what Michelangelo’s “god complex” may have started opens up new possibilities to what Joseph Campbell would eventually call “The Hero with a Thousand Faces.”

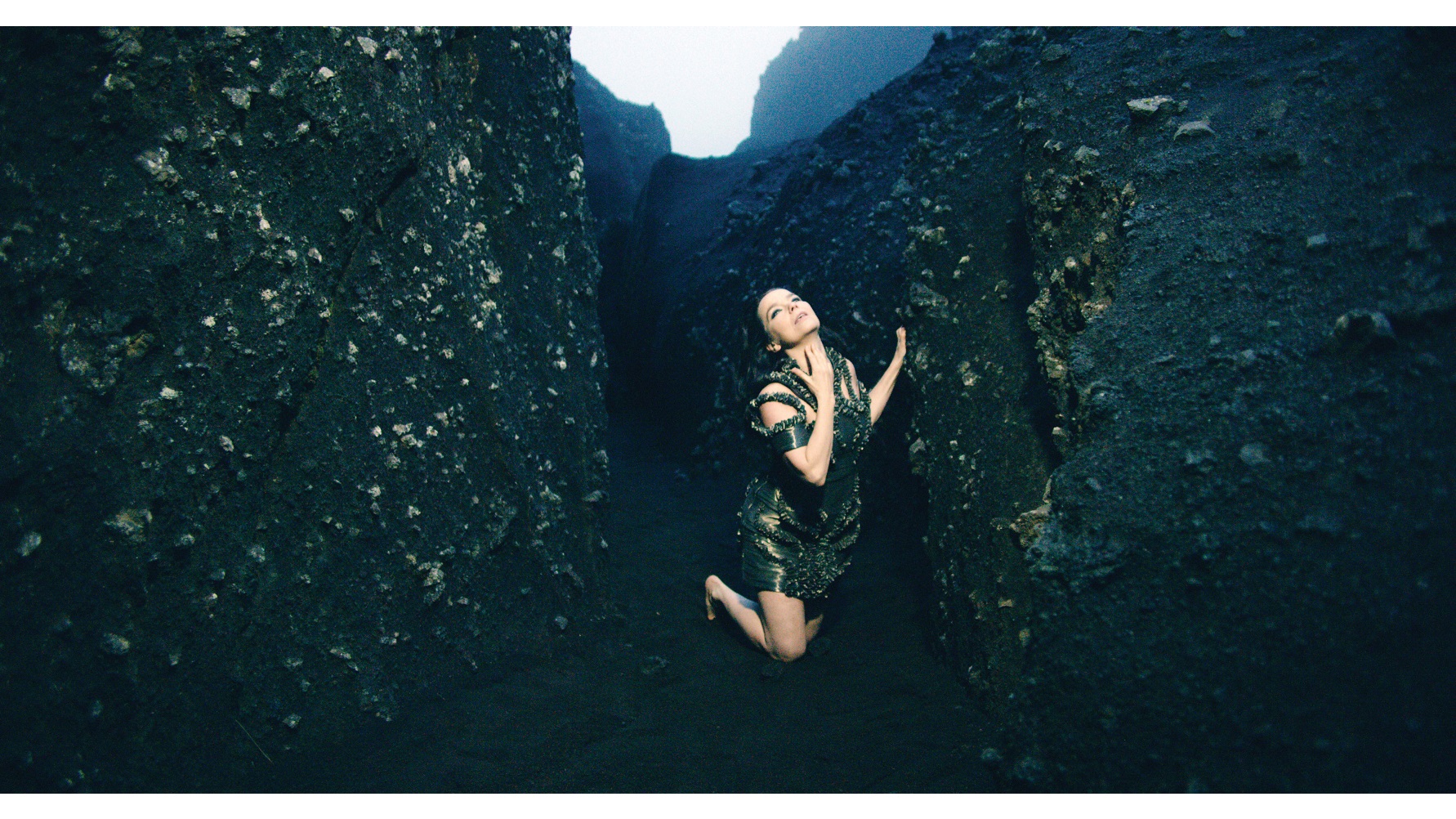

Image:Tityus, 1548‑1549. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (Museo de Nacional del Prado, Madrid). Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Another artist who knew and copied Michelangelo’s drawing was Titian, who painted his own version (shown above) just 16 years later. In the exhibition catalog, Atkins relates how Michelangelo and Titian came to personify “dueling aesthetic ideologies” during the Italian Renaissance that many “cast in … binary terms” of Michelangelo’s Florentian figurative and compositional power versus Titian’s Venetian “color and emotional force.” For Atkins, the marvel of Rubens’ achievement is in his ability to synthesize those two (grossly oversimplified) binaries. Rubens “synthesized diverse elements to arrive at a distinctive artistic voice” to “create the idiom that has come to define much of the Baroque aesthetic.” Rubens managed to look and wrestle with the past, managing not only to not lose himself, but also to actually find himself as never before.

Image: Prometheus Bound, Begun c. 1611‑12, completed by 1618. Peter Paul Rubens and Franz Snyders (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund). Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

And, yet, Rubens’ Prometheus Bound (shown above) tangles not just with Renaissance giants, but also with his contemporaries. Thanks to his role as a diplomat, Rubens traveled far and wide, visiting at least 50 European cities. A map at the start of the exhibition charts Rubens travels as well as the visual library he collected in memory. Atkins points out that Rubens’ dialogue with Michelangelo and Titian took place as part of a larger, multinational discourse. Michelangelo remained “modern” and revolutionary to early 17th century eyes. The sprawling figures of Michelangelo’s works led to a fad where it was literally raining men (Hallelujah) throughout the art world. Such foreshortened, muscled figures provided the perfect opportunity to show off ones skills while also measuring oneself against the masters. Selections from the PMA’s excellent print department drive home just how hard it was raining men, while a plaster cast reproduction of Laocoön and His Sons equally drives home how this visual dialogue went further back than even Michelangelo.

Image: Study for Prometheus, 1612. Franz Snyders (On loan from The British Museum, London: Donated by Count Antoine Seilern). Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This creative collaboration over time and space exists even in the composition of Rubens’ Prometheus Bound. Too often Rubens’ gets all the credit, with the man behind the eagle, Franz Snyders, left out in the cold. (Snyder’s study for the eagle appears above.) “Collaboration between two such masters was common practice in early 17th century Antwerp,” Atkins explains. Atkins likens the Rubens-Snyder team-up to a “duet” that allows the audience to enjoy the best of both worlds. In many ways Rubens and Snyder’s Prometheus Bound serves as a symbol of creativity itself — not a lonely enterprise but a collaboration, whether “standing on the shoulders of giants,” standing beside a partner, or (in this case) both.

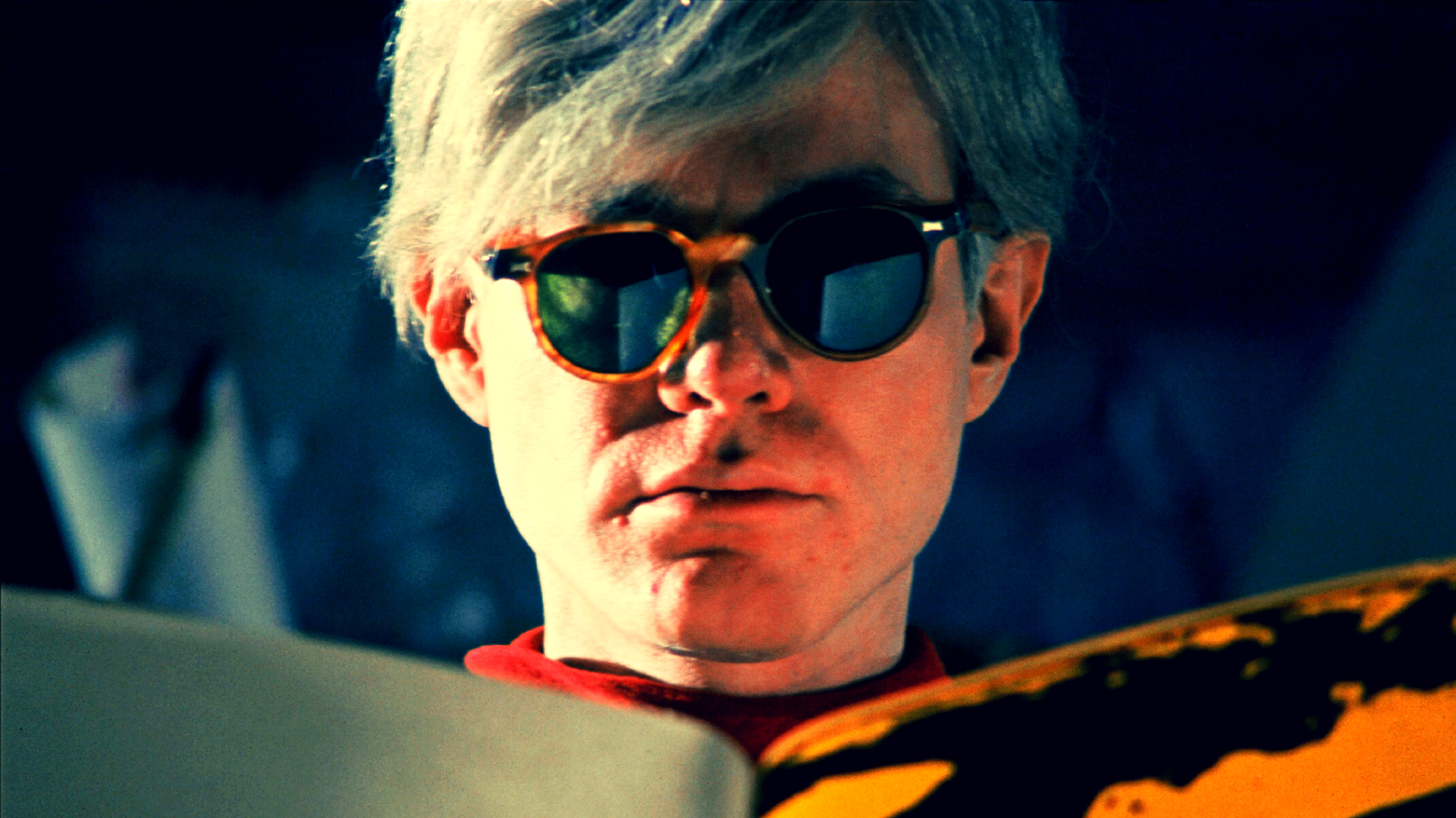

Image: Prometheus Eternal, 2015, Cover image: Bill Sienkiewicz, Comic book developed by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Published by Locust Moon Publishers.

The Wrath of the Gods: Masterpieces by Rubens, Michelangelo, and Titian manages to pull off the miracle of making art come alive with the spirit of its original creativity. I viewed the gallery as a school group listened to the story of the god who risked everything to bring fire to humanity and could see their young eyes and imaginations light up. Sparks fly all over the gallery as you make the visual connections all over again in your mind. Keeping those fires burning is a comic book inspired by the exhibition, Prometheus Eternal, whose title announces that the legend and its meaning will never die. From Bill Sienkiewicz’s evocative cover (shown above) to Andrea Tsurumi’s re-casting of Rubens as Renaissance fanboy to James Comey’s funny “Foie Gras” take on Prometheus’ liver, Prometheus Eternal proves that “the torch has been passed” (a phrase originating in the Prometheus legend) to today. Rubens may have flipped the script on Michelangelo, but the story itself never ends.

[Image at Top of Post: (Left) Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Last Judgment (detail), 1536–1541. Image source:Wikipedia. (Right) Prometheus Bound, Begun c. 1611‑12, completed by 1618. Peter Paul Rubens and Franz Snyders (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund). Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with the images above from, a review copy of the catalog to, a review copy of the comic book Prometheus Eternal about, other press materials for, and a press pass to the exhibition The Wrath of the Gods: Masterpieces by Rubens, Michelangelo, and Titian, which runs through December 6, 2015.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]