Cheever’s Facebook

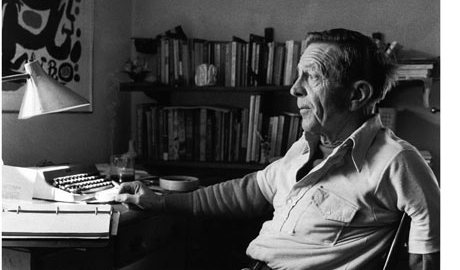

Edmund White’s eloquent consideration of Cheever in the new New York Review of Books remembers the late author’s connections with Chekhov, his love/hate relationship with Catcher in the Rye, and his short story, “The Enormous Radio,” in which one woman is brought to despair via an excess of information from her neighbors.

White writes:

Again and again Cheever nests one story into another. One of his first successful stories, “The Enormous Radio,” is about a young wife in New York who listens to a new radio all day that, strangely enough, is tuned in not to broadcasts but to the conversations going on in the adjoining apartments. When her husband comes home one day she’s a wreck. She sobs:

‘They’re all worried about money. Mrs. Hutchinson’s mother is dying of cancer in Florida and they don’t have enough money to send her to the Mayo Clinic. At least, Mr. Hutchinson says they don’t have enough money. And some woman in this building is having an affair with the handyman—with that hideous handyman. It’s too disgusting. And Mrs. Melville has heart trouble and Mr. Hendricks is going to lose his job in April and Mrs. Hendricks is horrid about the whole thing and that girl who plays the “Missouri Waltz” is a whore, a common whore, and the elevator man has tuberculosis and Mr. Osborn has been beating Mrs. Osborn.’

The consoling husband has the radio removed—other people’s stories may be gripping but they can also have such a sad cumulative effect that they make one’s own life impossible to live.

Isn’t this us, now? What is Facebook other than the magic radio, tuning us in “accidentally” to The Lives of Others, and leaving us feeling the addictive, quick euphoria of new information? Will we hang on to it, or will we ultimately beg our lovers to dismantle the machinery, leaving us free—not only to remember life without the constant hum and rush of detail but, moreover, life in which we grow by using our own imaginations.

White’s last words on Cheever reinforce the latter’s charms as explicitly sensual:

The vitality and fantasy of Cheever’s writing, even when he is at his most serious, stand in complete contrast to the despair and loneliness and boredom of his life. What was it that allowed him to transform all this dullness into art? My own answer may sound trivializing but I would say it was his knack for writing seductively about the world of the senses—its colors and associations, its sexiness and its smells (above all, its smells!), not to mention its suave beauty, at once transitory and eternal in a way that Wallace Stevens understood in that paradoxical line of “Peter Quince at the Clavier”: “The body dies; the body’s beauty lives.

The is the opposite of the banality of gossip; this is the rare incandescence of prose.