A leader’s guide to the chaotic reality of leadership

- Successful leaders can seem like they have it all figured out.

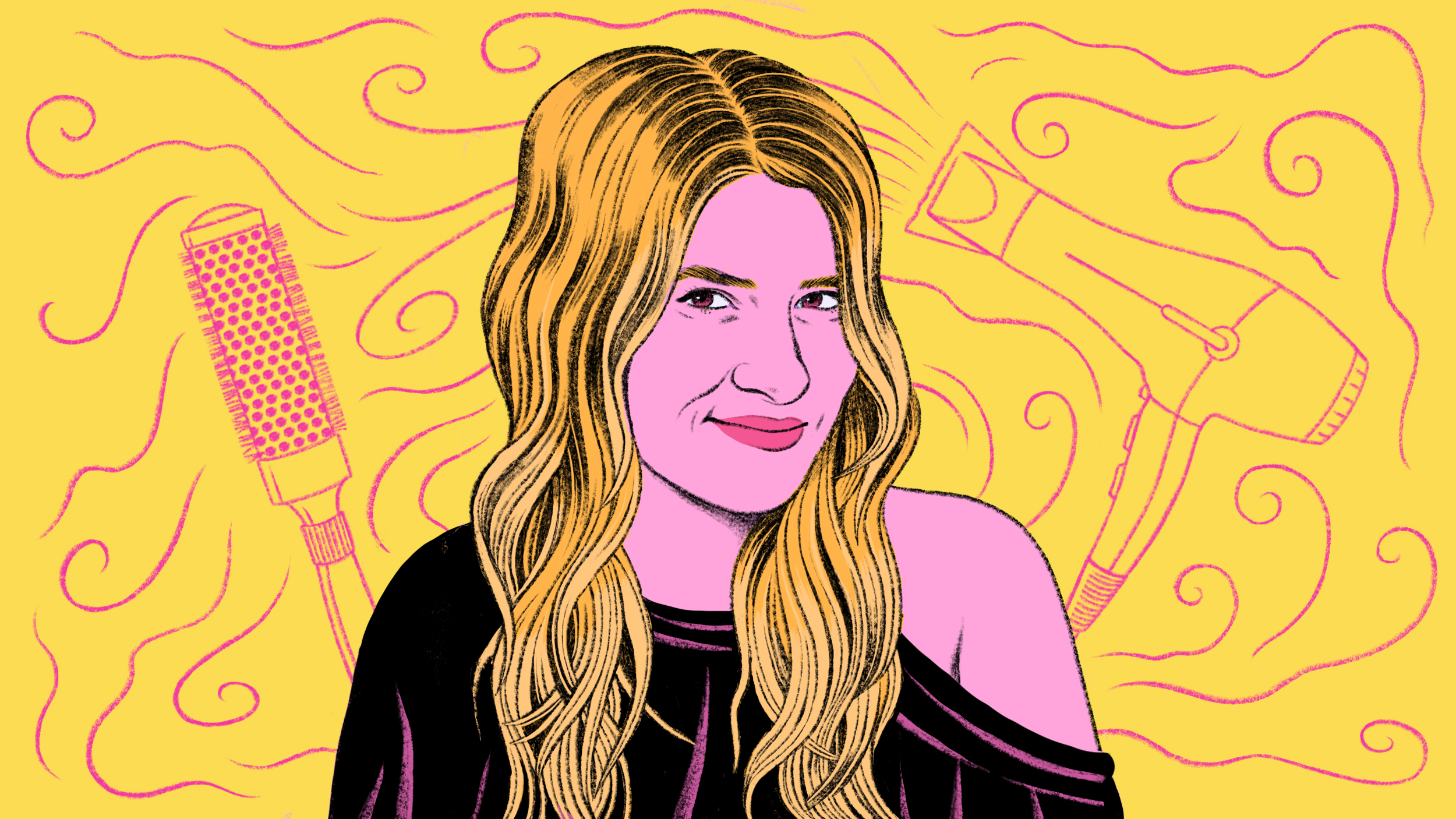

- Alli Webb, co-founder of Drybar, says that leadership is messy and we should learn to embrace that.

- She recommends that up-and-coming leaders lean into impostor syndrome, recognize that balance is an illusion, and don’t be afraid of mixing work and personal life.

Up-and-coming leaders often look to role models for guidance. The stories of established business people can offer assurance during troubling times and strategies for the innumerable challenges any leader must face. Sometimes, though, the image of success can obscure the truth of leadership and create misleading takeaways.

Consider, for instance, those leaders who seem to have all the answers all the time. They move from triumph to triumph effortlessly. They command the stage with their presence, light up the room with their charm, and always have a witty retort at the ready. Heck, they don’t even seem to have bad hair days!

The misleading takeaway their well-manicured image imparts: They’ve got their sh*t together. Why can’t you manage yours?

Of course, such perfection is a far cry from reality. It is the result of careful editing, well-rehearsed speeches, and biographies written as saintly gospel (to the exclusion of the unsightly truth). That truth being that leadership is messy. It’s difficult. It’s unwieldy, and even the best outcomes are anything but perfect.

Alli Webb, co-founder of Drybar, knows this truth all too well. As chronicled in her recent memoir, The Messy Truth, she struggled on the path to building a $255 million business. Her mental health suffered, her personal life could be disorderly, and she was plagued with self-doubt.

After looking back on her journey, Webb offers a less neat, but far more real, lesson to leaders: Embrace the mess. Big Think recently sat down with her to discuss how to do just that.

1. Keep your lightbulb ideas bright

Many successful businesses have been kick-started in a founder’s garage, but Drybar arguably had even humbler beginnings: the trunk of Webb’s car.

In the late aughts, Webb began a mobile business called Straight at Home. Driven by her lifelong “love affair with hair,” she would travel to clients’ houses and provide at-home blowout services. As the business grew, it soon became apparent that the demand exceeded a one-woman operation. What if, Webb thought, she started a brick-and-mortar salon that exclusively offered blowouts?

That thought was the lightbulb idea that led to Drybar, but two things helped keep the idea bright for her as she took the initial steps to build it.

First, the idea energized her and those she shared it with. Her husband at the time thought it showed promise. Her brother, Michael Landau, thought so too and even agreed to become a co-founder. “Everybody I talked to about the idea loved it so much. That gave me confidence,” she says.

Now, Webb is quick to note that not everybody needs to love your idea for it to be great. Some people will be enthused, others won’t. That’s the nature of new ideas. Rather, it’s that early support can help you overcome the difficult steps of taking an idea from thought to reality.

Second, the idea doesn’t have to be extravagant to be great. In fact, Webb recommends starting small.

Her initial plan wasn’t to build a $255 million business. All she wanted was enough clients to support a blowout salon in LA. That’s it. But by starting small, she kept the challenge manageable, learned important lessons early, and offered herself room to grow along the way.

2. Welcome impostor syndrome

Drybar didn’t stay a one-salon business for long, though, and Webb soon began to struggle — not only with the challenges of managing the business but also with the recognition her success brought.

For instance, she would often earn spots on top business or influencer lists alongside the names of people she greatly admired. She felt embarrassed and unworthy of the honor. In other words, she felt like an impostor. But while most people would seek a way to overcome their impostor syndrome, Webb leaned in and discovered its value.

“You’re an imposter in this role or situation … and that’s awesome! You’re embarking on something that you haven’t done before.”

Alli Webb

“I realized that all imposter syndrome is is not feeling like you should be where you are, right? You’re an imposter in this role or situation or whatever it is,” Webb explains. “And that’s awesome! You’re embarking on something that you haven’t done before. That’s amazing.”

Recognizing this helped Webb reframe her mindset. She realized that the physical sensations her impostor syndrome manifested — the sweat, the racing heart, the fast breathing — were the same feelings she felt when excited. Anxiety and excitement became “two sides of the same emotional coin.” So rather than let those sensations overwhelm her, they came to be a source of motivation and drive instead.

“You’re nervous, but you also think you’re going to be great at [this new thing]. That’s the beauty of impostor syndrome,” Webb says. She adds that by adopting this frame of mind, “you won’t be an impostor for long.”

3. Recognize the illusion of balance

As Drybar grew, things got busier, and the daily to-do felt like trying to hit multiple moving targets with a single arrow. Be a good mom, a good wife, and a good business owner. Take care of yourself, your team, and your family. Look good but also feel good while making all that good look effortless.

Except the targets never align, and that elusive work-life balance remained, well, elusive. Over time, Webb realized: “Trying to be all of these things in perfect balance, it just doesn’t exist. Not for me anyway, and I don’t know that it does for anybody I’ve met.”

Webb’s advice is to let go of balance and learn to calibrate based on the day. Some days, she could show up for her kids — make them dinner, help them with their homework, and enjoy some hangout time. Other times, she had to work out of town or prepare for a speaking event, and she couldn’t do those at-home things well.

Ultimately, today’s concept of balance “is an unattainable expectation that we put on ourselves” and one we’d do better setting aside for more realistic expectations.

4. Mix work with your personal life

One mistake Webb admits to making at Drybar is being too guarded. She didn’t open up about her personal challenges and kept everything bottled up rather than reaching out to colleagues and coworkers.

She took to heart the age-old ethos to keep work and personal life separate, and she paid the price. When conflicts arose, she didn’t know how to effectively deal with the people involved. She also became avoidant when open dialogue was necessary.

“I think it is probably an age thing, of experiencing so much life and its many ups and downs, and the people who have impacted my life. I’ve just come to realize that we take ourselves and our sh*t wherever we go,” Webb says.

“One of the best things you can do [as a leader] is help other people become great.”

Alli Webb

Today, Webb has learned from those experiences and can confide in her colleagues when she needs someone to listen (and vice versa). That said, Webb warns, there is a line between being open and authentic, and oversharing. You can be honest and give high-level details without bringing drama into the workspace.

“I think the more you know about your people, it’s just better karma in life. It’s also better business. It’s like, ‘Oh, we’re all connected here and really care.’ That changes the dynamic of any situation,” Webb says.

5. Let your team light up your ideas

Like many leaders, Webb could be overprotective of her idea. She worried that one gaff, one mistake, one slip-up, one bad decision, and the whole business would go bust. As such, she wanted to be involved in every decision and make sure everything was done right.

With the gift of hindsight, she realizes: “I made tons of bad calls, and the business was fine ultimately. My advice would be to listen to people and learn because I can tell you the pain of gripping something too tightly. It is not going to serve you or anybody else in the long run.”

It took time — years Webb admits — but she came to recognize that she needed to allow other people the same privilege of making mistakes and learning from them. She also realized that she had built a team of smart, talented people who were passionate about the business. That allowed her to step back, trust them, and see what they could accomplish.

“One of the best things you can do [as a leader] is help other people become great,” Webb says.

6. Don’t sweep your mess under the rug

Webb’s final takeaway is that perfection is not synonymous with success. You don’t have to have all the answers. You can stumble and steer through setbacks. You can learn lessons and lean on that team of people you have around you.

That vulnerability isn’t a sign of weakness; it’s a sign of being a person who is trying their best. And that, in turn, empowers the people around you to try their best.

“It’s such bullsh*t,” Webb said. “I didn’t know a lot of things. I pretended to have the answers, but I wouldn’t do that again. It’s okay to say, ‘Yeah, I don’t really know. What do you think? Let’s go figure it out together!’ That’s such a more empowering stance as a leader that I really embrace now.”