Psychology’s 10 greatest case studies – digested

These ten characters have all had a huge influence on psychology and their stories continue to intrigue each new generation of students. What’s particularly fascinating is that many of their stories continue to evolve – new evidence comes to light, or new technologies are brought to bear, changing how the cases are interpreted and understood. What many of these 10 also have in common is that they speak to some of the perennial debates in psychology, about personality and identity, nature and nurture, and the links between mind and body.

Phineas Gage

One day in 1848 in Central Vermont, Phineas Gage was tamping explosives into the ground to prepare the way for a new railway line when he had a terrible accident. The detonation went off prematurely, and his tamping iron shot into his face, through his brain, and out the top of his head.

Remarkably Gage survived, although his friends and family reportedly felt he was changed so profoundly (becoming listless and aggressive) that “he was no longer Gage.” There the story used to rest – a classic example of frontal brain damage affecting personality. However, recent years have seen a drastic reevaluation of Gage’s story in light of new evidence. It’s now believed that he underwent significant rehabilitation and in fact began work as a horse carriage driver in Chile. A simulation of his injuries suggested much of his right frontal cortex was likely spared, and photographic evidence has been unearthed showing a post-accident dapper Gage. Not that you’ll find this revised account in many psychology textbooks: a recent analysis showed that few of them have kept up to date with the new evidence.

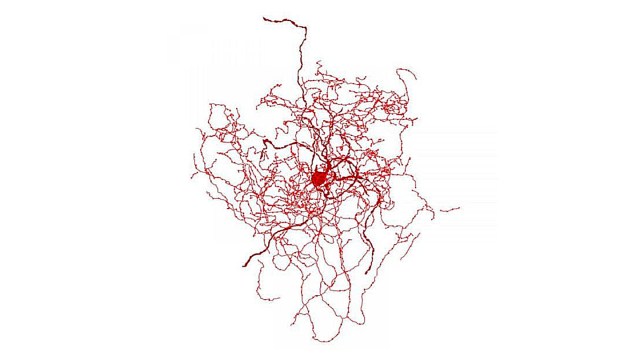

H.M.

Henry Gustav Molaison (known for years as H.M. in the literature to protect his privacy), who died in 2008, developed severe amnesia at age 27 after undergoing brain surgery as a form of treatment for the epilepsy he’d suffered since childhood. He was subsequently the focus of study by over 100 psychologists and neuroscientists and he’s been mentioned in over 12,000 journal articles! Molaison’s surgery involved the removal of large parts of the hippocampus on both sides of his brain and the result was that he was almost entirely unable to store any new information in long-term memory (there were some exceptions – for example, after 1963 he was aware that a US president had been assassinated in Dallas). The extremity of Molaison’s deficits was a surprise to experts of the day because many of them believed that memory was distributed throughout the cerebral cortex. Today, Molaison’s legacy lives on: his brain was carefully sliced and preserved and turned into a 3D digital atlas and his life story is reportedly due to be turned into a feature film based on the book researcher Suzanne Corkin wrote about him: Permanent Present Tense, The Man With No Memory and What He Taught The World.

Victor Leborgne (nickname “Tan”)

The fact that, in most people, language function is served predominantly by the left frontal cortex has today almost become common knowledge, at least among psych students. However, back in the early nineteenth century, the consensus view was that language function (like memory, see entry for H.M.) was distributed through the brain. An eighteenth century patient who helped change that was Victor Leborgne, a Frenchman who was nicknamed “Tan” because that was the only sound he could utter (besides the expletive phrase “sacre nom de Dieu”). In 1861, aged 51, Leborgne was referred to the renowned neurologist Paul Broca, but died soon after. Broca examined Leborgne’s brain and noticed a lesion in his left frontal lobe – a segment of tissue now known as Broca’s area. Given Leborgne’s impaired speech but intact comprehension, Broca concluded that this area of the brain was responsible for speech production and he set about persuading his peers of this fact – now recognised as a key moment in psychology’s history. For decades little was known about Leborgne, besides his important contribution to science. However, in a paper published in 2013, Cezary Domanski at Maria Curie-Sklodowska University in Poland uncovered new biographical details, including the possibility that Leborgne muttered the word “Tan” because his birthplace of Moret, home to several tanneries.

Wild Boy of Aveyron

The “Wild boy of Aveyron” – named Victor by the physician Jean-Marc Itard – was found emerging from Aveyron forest in South West France in 1800, aged 11 or 12, where’s it’s thought he had been living in the wild for several years. For psychologists and philosophers, Victor became a kind of “natural experiment” into the question of nature and nurture. How would he be affected by the lack of human input early in his life? Those who hoped Victor would support the notion of the “noble savage” uncorrupted by modern civilisation were largely disappointed: the boy was dirty and dishevelled, defecated where he stood and apparently motivated largely by hunger. Victor acquired celebrity status after he was transported to Paris and Itard began a mission to teach and socialise the “feral child”. This programme met with mixed success: Victor never learned to speak fluently, but he dressed, learned civil toilet habits, could write a few letters and acquired some very basic language comprehension. Autism expert Uta Frith believes Victor may have been abandoned because he was autistic, but she acknowledges we will never know the truth of his background. Victor’s story inspired the 2004 novel The Wild Boy and was dramatised in the 1970 French film The Wild Child.

Kim Peek

Nicknamed ‘Kim-puter’ by his friends, Peek who died in 2010 aged 58, was the inspiration for Dustin Hoffman’s autistic savant character in the multi-Oscar-winning film Rain Man. Before that movie, which was released in 1988, few people had heard of autism, so Peek via the film can be credited with helping to raise the profile of the condition. Arguably though, the film also helped spread the popular misconception that giftedness is a hallmark of autism (in one notable scene, Hoffman’s character deduces in an instant the precise number of cocktail sticks – 246 – that a waitress drops on the floor). Peek himself was actually a non-autistic savant, born with brain abnormalities including a malformed cerebellum and an absent corpus callosum (the massive bundle of tissue that usually connects the two hemispheres). His savant skills were astonishing and included calendar calculation, as well as an encyclopaedic knowledge of history, literature, classical music, US zip codes and travel routes. It was estimated that he read more than 12,000 books in his life time, all of them committed to flawless memory. Although outgoing and sociable, Peek had coordination problems and struggled with abstract or conceptual thinking.

Anna O.

“Anna O.” is the pseudonym for Bertha Pappenheim, a pioneering German Jewish feminist and social worker who died in 1936 aged 77. As Anna O. she is known as one of the first ever patients to undergo psychoanalysis and her case inspired much of Freud’s thinking on mental illness. Pappenheim first came to the attention of another psychoanalyst, Joseph Breuer, in 1880 when he was called to her house in Vienna where she was lying in bed, almost entirely paralysed. Her other symptoms include hallucinations, personality changes and rambling speech, but doctors could find no physical cause. For 18 months, Breuer visited her almost daily and talked to her about her thoughts and feelings, including her grief for her father, and the more she talked, the more her symptoms seemed to fade – this was apparently one of the first ever instances of psychoanalysis or “the talking cure”, although the degree of Breuer’s success has been disputed and some historians allege that Pappenheim did have an organic illness, such as epilepsy. Although Freud never met Pappenheim, he wrote about her case, including the notion that she had a hysterical pregnancy, although this too is disputed. The latter part of Pappenheim’s life in Germany post 1888 is as remarkable as her time as Anna O. She became a prolific writer and social pioneer, including authoring stories, plays, and translating seminal texts, and she founded social clubs for Jewish women, worked in orphanages and founded the German Federation of Jewish Women.

Kitty Genovese

Sadly, it is not really Kitty Genovese the person who has become one of psychology’s classic case studies, but rather the terrible fate that befell her. In 1964 in New York, Genovese was returning home from her job as a bar maid when she was attacked and eventually murdered by Winston Mosely. What made this tragedy so influential to psychology was that it inspired research into what became known as the Bystander Phenomenon – the now well-established finding that our sense of individual responsibility is diluted by the presence of other people. According to folklore, 38 people watched Genovese’s demise yet not one of them did anything to help, apparently a terrible real life instance of the Bystander Effect. However, the story doesn’t end there because historians have since established the reality was much more complicated – at least two people did try to summon help, and actually there was only one witness the second and fatal attack. While the main principle of the Bystander Effect has stood the test of time, modern psychology’s understanding of the way it works has become a lot more nuanced. For example, there’s evidence that in some situations people are more likely to act when they’re part of a larger group, such as when they and the other group members all belong to the same social category (such as all being women) as the victim.

Little Albert

“Little Albert” was the nickname that the pioneering behaviourist psychologist John Watson gave to an 11-month-old baby, in whom, with his colleague and future wife Rosalind Rayner, he deliberately attempted to instill certain fears through a process of conditioning. The research, which was of dubious scientific quality, was conducted in 1920 and has become notorious for being so unethical (such a procedure would never be given approval in modern university settings). Interest in Little Albert has reignited in recent years as an academic quarrel has erupted over his true identity. A group led by Hall Beck at Appalachian University announced in 2011 that they thought Little Albert was actually Douglas Merritte, the son of a wet nurse at John Hopkins University where Watson and Rayner were based. According to this sad account, Little Albert was neurologically impaired, compounding the unethical nature of the Watson/Rayner research, and he died aged six of hydrocephalus (fluid on the brain). However, this account was challenged by a different group of scholars led by Russell Powell at MacEwan University in 2014. They established that Little Albert was more likely William A Barger (recorded in his medical file as Albert Barger), the son of a different wet nurse. Earlier this year, textbook writer Richard Griggs weighed up all the evidence and concluded that the Barger story is the more credible, which would mean that Little Albert in fact died 2007 aged 87.

Chris Sizemore

Chris Costner Sizemore is one of the most famous patients to be given the controversial diagnosis of multiple personality disorder, known today as dissociative identity disorder. Sizemore’s alter egos apparently included Eve White, Eve Black, Jane and many others. By some accounts, Sizemore expressed these personalities as a coping mechanism in the face of traumas she experienced in childhood, including seeing her mother badly injured and a man sawn in half at a lumber mill. In recent years, Sizemore has described how her alter egos have been combined into one united personality for many decades, but she still sees different aspects of her past as belonging to her different personalities. For example, she has stated that her husband was married to Eve White (not her), and that Eve White is the mother of her first daughter. Her story was turned into a movie in 1957 called The Three Faces of Eve (based on a book of the same name written by her psychiatrists). Joanne Woodward won the best actress Oscar for portraying Sizemore and her various personalities in this film. Sizemore published her autobiography in 1977 called I’m Eve. In 2009, she appeared on the BBC’s Hard Talk interview show.

David Reimer

One of the most famous patients in psychology, Reimer lost his penis in a botched circumcision operation when he was just 8 months old. His parents were subsequently advised by psychologist John Money to raise Reimer as a girl, “Brenda”, and for him to undergo further surgery and hormone treatment to assist his gender reassignment.

Money initially described the experiment (no one had tried anything like this before) as a huge success that appeared to support his belief in the important role of socialisation, rather than innate factors, in children’s gender identity. In fact, the reassignment was seriously problematic and Reimer’s boyishness was never far beneath the surface. When he was aged 14, Reimer was told the truth about his past and set about reversing the gender reassignment process to become male again. He later campaigned against other children with genital injuries being gender reassigned in the way that he had been. His story was turned into the book As Nature Made Him, The Boy Who Was Raised As A Girl by John Colapinto, and he is the subject of two BBC Horizon documentaries. Tragically, Reimer took his own life in 2004, aged just 38.

Christian Jarrett (@Psych_Writer) is Editor of BPS Research Digest

This article was originally published on BPS Research Digest. Read the original article.