Predator Nation Author Says Crime Pays Very Well On Wall Street

The first thing that came to mind when I finished Predator Nation, the book by Charles Ferguson that explains how Wall Street’s elite brazenly commit financial crimes out in the open, is that nothing he wrote about is a secret. The Know Nothing movement has succeeded in getting the American public to cheer for the very same “heroes” in Wall Street investment houses while they are in the act of pissing away hundreds upon hundreds of billions of the public’s pension fund and investor dollars. Mr. Ferguson’s book had me at the phrase “corporate criminals, public corruption, and the hijacking of America” that is emblazoned across the book’s fire engine red book cover. Some of his more inspired invective reminded me of my own blog posts that enthusiastically attempted to indict the financial services sector for ignoring the law.

In an unintended bit of irony, Mr. Ferguson wonders, as he laments that today’s mega banks are too big to succeed, “how JP Morgan Chase will fare once Jamie Dimon retires.” We may soon find out. In Chapter Six I had to smile as I read the following paragraph:

“It is no exaggeration to say that since the 1980’s, much of the American (and global) financial sector has become criminalized, creating an industry that tolerates or even encourages systemic fraud. The behavior that caused the mortgage bubble and financial crisis was a natural outcome and continuation of this pattern, rather than some kind of economic accident.”

Charles Ferguson, Predator Nation

If you were a blogger back in 2008, your blog posts wrote themselves, because you were so outraged at what the mainstream media wouldn’t say about what was happening on Wall Street. You laughed at the way the words “non-reviewable” jumped out at you from the one page directive Hank Paulson wrote to detail to Congress how he was going to oversee and manage the 700 billion dollars he requested to bailout the Wall Street banks. You howled when it was disclosed that the very same money center banks had access to trillions from the Fed that made 700 billion look like chump change. Ferguson’s book brought it all back in vivid, living color and easy to read language that was specific without being overly pedantic.

Most of us don’t want the details, though. We want the synopsis. We want the Cliff’s Notes version. We want the soundbite that we can digest while we are flipping channels during an NBA Finals commercial break. For most things that we form opinions about in life, you can get by with that approach. Moral righteousness alone is often enough to validate your position, even if you have no understanding of the actual mechanics underpinning a controversial situation.

But to even voice an opinion on this, you have got to be able to grasp the importance of a few key financial and legal details in a way that allows you to understand how this alternate universe of high finance has completely upended the “positive outcome equals good, negative outcome equals bad” mantra we use to gauge whether or not the impetus behind much of the decision making in the manufacture of derivatives is to be labeled “good” or “bad.”

One of the main themes in Ferguson’s book deals with the reluctance of Wall Street to accept regulations, even though they have proved over and over since the S&L crisis that they are dyed-in-the-wool repeat offenders. Ferguson contends that “there are five principal drivers of catastrophic risk in modern unregulated finance. They are volatility, leverage, structural concentration, systemic interdependence and toxic incentives.” The section of the book that was news to me chronicled in great detail exactly how well known economists like Laura Tyson and Martin Feldstein make millions by selling the imprimatur of their academic veneer to Wall Street banks who want to bolster their arguments for less regulations.

In an otherwise solid effort that seems calibrated towards the vast majority of the American population whose financial instrument IQ’s are in the single digits, it is hard to tell whether Ferguson deliberately left out any mention of the Gaussian copula function formula devised by David X. Li which made all of the triple A ratings for the bond pools holding subprime mortgages possible.

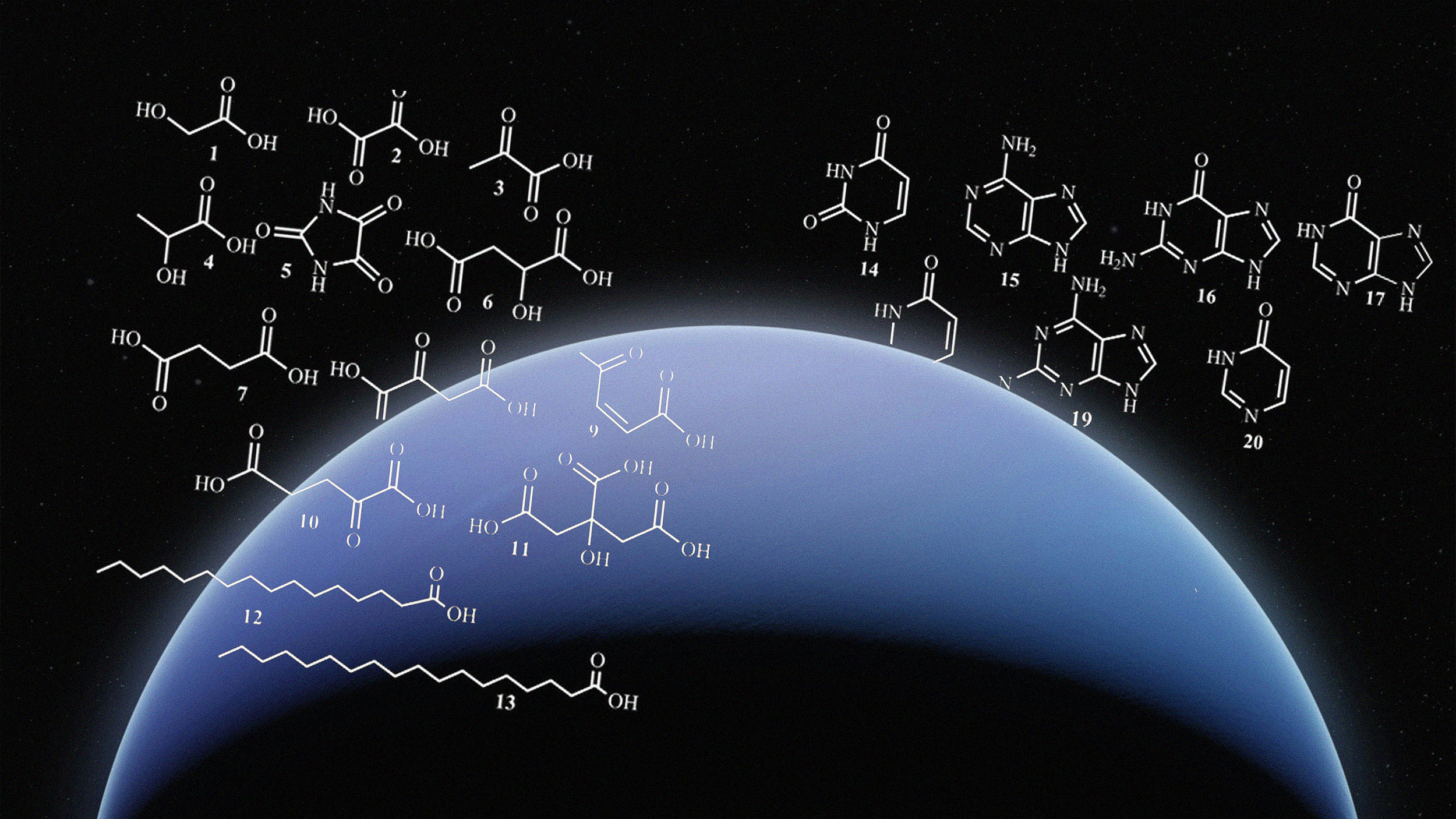

When the price of a credit default swap goes up, that indicates that default risk has risen. Li’s breakthrough was that instead of waiting to assemble enough historical data about actual defaults, which are rare in the real world, he used historical prices from the CDS market. It’s hard to build a historical model to predict Alice’s or Britney’s behavior, but anybody could see whether the price of credit default swaps on Britney tended to move in the same direction as that on Alice. If it did, then there was a strong correlation between Alice’s and Britney’s default risks, as priced by the market.

Li wrote a model that used price rather than real-world default data as a shortcut (making an implicit assumption that financial markets in general, and CDS markets in particular, can price default risk correctly). It was a brilliant simplification of an intractable problem. And Li didn’t just radically dumb down the difficulty of working out correlations; he decided not to even bother trying to map and calculate all the nearly infinite relationships between the various loans that made up a pool. What happens when the number of pool members increases or when you mix negative correlations with positive ones? Never mind all that, he said. The only thing that matters is the final correlation number—one clean, simple, all-sufficient figure that sums up everything.

The effect on the securitization market was electric. Armed with Li’s formula, Wall Street’s quants saw a new world of possibilities. And the first thing they did was start creating a huge number of brand-new triple-A securities.

Using Li’s copula approach meant that ratings agencies like Moody’s—or anybody wanting to model the risk of a tranche—no longer needed to puzzle over the underlying securities. All they needed was that correlation number, and out would come a rating telling them how safe or risky the tranche was.

Recipe for Disaster: The Formula That Killed Wall Street

What makes the book and the documentary preceding it, Inside Job, so unique is Mr. Ferguson’s background. He is not an outsider looking in, as most of us in the blogosphere were, but someone who has been associated at a high level with the industry professionally for years, an insider with enough clout to get the dean of Columbia Business School and a former Federal Reserve governor to talk to him on camera about the dark side of Wall Street in his documentary. Maybe this publication will get more folks from the financial sector who are tired of living a lie to come forward and stand with the Charles Fergusons and the Simon Johnsons of the world.