Study Warns of Boomerang Effects in Climate Change Campaigns

Climate change campaigns in the United States that focus on the risks to people in foreign countries or even other regions of the U.S. are likely to inadvertently increase polarization among Americans rather than build consensus and support for policy action. In contrast, locally focused campaigns that highlight the risks to fellow residents of a state or a city are less likely to activate strong partisan differences.

Those are the conclusions of a forthcoming study published online this week at Communication Research. The study is co-authored by Sol Hart, a faculty colleague in the School of Communication at American University and by my brother Erik Nisbet, a professor at Ohio State University. A PDF of the study is posted at the Climate Shift Project web site where Hart and Nisbet serve as faculty fellows.

The study investigates the general problem of boomerang effects in climate change campaigns and advocacy. A boomerang effect occurs when a message is strategically constructed with a specific intent but produces a result that is the opposite of that intent. Previous studies, for example, indicate that the use of dire messages warning of climate catastrophe may unintentionally trigger disbelief, skepticism, and/or decreased concern among audiences.

Hart and Nisbet were curious to examine other features of climate change campaigns that might backfire. In particular, they wanted to understand how those portrayed as suffering from the impacts of climate change might trigger differential perceptions among Republicans and Democrats, shaping support for policy action.

Motivated Reasoning and Social Identification

As political communication researchers have closely tracked, both Democrats and Republicans tend to engage in strong forms of motivated reasoning, selectively seeking out and interpreting information across issues in a way that reinforces existing political views and that is in line with their ideology.

Hart and Nisbet expected that this tendency to engage in motivated reasoning would interact with the additional natural tendency to rely on social closeness or sameness as a short cut in making sense of a policy problem.

Research shows that individuals are more likely to support action on a problem when those threatened or at risk are perceived as more socially similar. Conversely, when those affected are perceived as more socially distant, support for action is likely to be less.

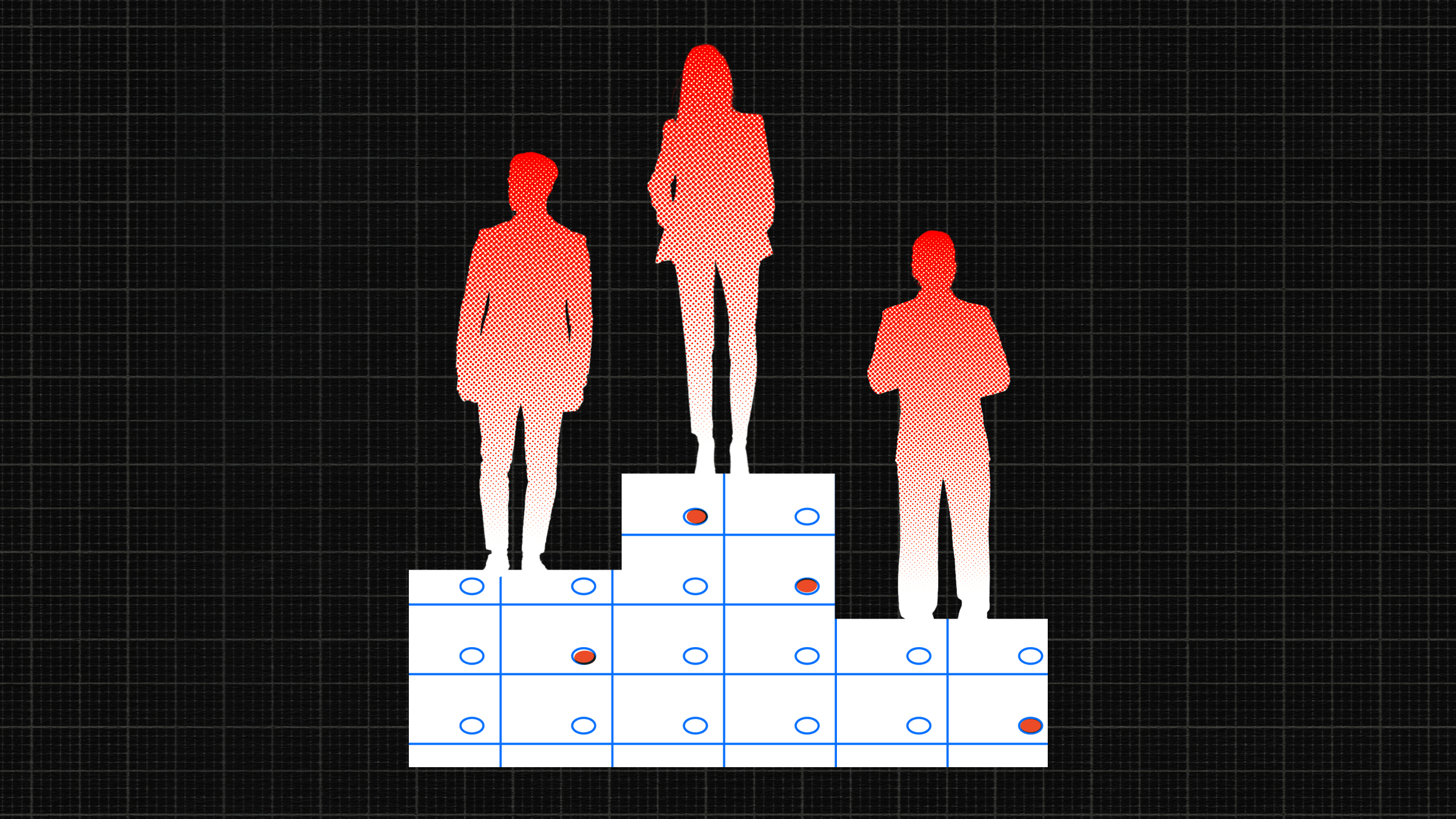

The schematic below summarizes Hart and Nisbet’s expectations relative to how motivated reasoning and perceived social distance might combine to shape the effects of climate change campaigns.

In designing their study, they expected that if presented with information about the risks of climate change to people living in other countries or states, Republicans would be less likely to identify with these victims than Democrats. They reasoned that Republicans’ existing doubts about climate change would serve to filter their concern and empathy while Democrats’ higher levels of concern would boost identification with the portrayed victims.

In the causal chain shaping perceptions, the differential level of identification with those threatened by the problem would in turn shape support for policy action. The stronger the identification with the portrayed victims, the greater the support for action.

But how would Republicans react to climate change messages that focused on the risks to people in their own state and communities? The answer to that question potentially points to a path forward in communicating about climate change.

Research Design

To examine this process, Hart and Nisbet conducted experiments involving 240 residents of central New York. In the two experimental conditions, participants read a simulated news story about climate change. No story was read in the one control condition.

The two simulated new stories were designed to be “nonpolitical” as they did not contain any explicit political partisan cues and focused on the potential health impacts of climate change. The stories discussed the potential for climate change to increase the likelihood that diseases such as West Nile virus will infect farmers and other individuals who spend a lot of time working outdoors. The news stories were generated explicitly for the experiment but were based on facts reported by the Associated Press. The story included pictures and names of eight farmers who were potentially at risk.

The two experimental conditions varied by manipulating the identity of the potential victims by low and high social distance. This was done by altering the story’s headline, body text, and victim’s names while keeping the victim photos in each story constant in order to guard against different facial expressions or other individual cues. In the high social distance condition, the potential victims were located either in the state of Georgia or the country France. In the low social distance condition, the potential victims of climate change were described as being located in upstate New York.

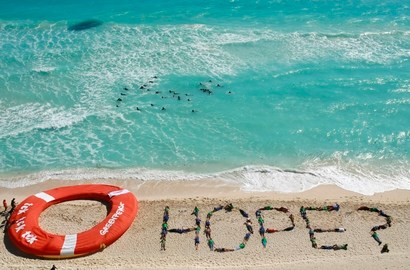

Here’s the high social distance condition, focusing on farmers in France:

Here’s the experimental condition for low social distance, focusing on the threat to farmers in upstate New York.

Measures

Social identification was measured by asking participants how much they agreed with the following statements with scores aggregated into a combined index:

Support for government action on climate was measured by asking participants how much they agreed with the following statements with scores aggregated into an index:

In their analysis, Hart and Nisbet also included survey item measures that controlled for general belief in man-made climate change, climate change knowledge, general science literacy, gender, age, and level of education. A standard measure was used to sort respondents by partisanship.

Results and Implications

Regardless of message condition — whether victims were portrayed as living in France/Georgia or New York — Democrats given their political identity and existing levels of concern over climate change were likely to identify with the affected farmers. In contrast, both Republicans and Independents indicated low social identification with the farmers as portrayed in the French/Georgia socially distant condition.

Moreover, as an outcome of differences in perceived social affinity, Republicans presented with information about the risks to French/Georgian farmers were were more likely to oppose policy action than their Republican counterparts in the control condition or in the upstate New York condition.

The importance of climate change campaigns and how subtle and not-so-subtle features might interact with the background of different audiences was underscored by another key finding of the analysis: After controls, neither knowledge specific to climate change or general science literacy was significantly related to support for policy action.

The study also points to a strategy supported by other recent research. In this work, when information about the risks of climate change are localized, connected closely to values such as public health, and communicated in terms of co-benefits to the community, these campaign efforts are likely to be more successful at transcending ideological differences and building support for action.

From the conclusion to the Hart and Nisbet study:

This study demonstrates the importance of deepening our understanding of how audience predispositions may interact with the characteristics of informational science messages. In this case, embedded social identity cues interacted with political orientations to amplify public polarization on the controversial science issue, climate change. Furthermore, neither factual knowledge about global warming nor general scientific knowledge was associated for support for climate mitigation policies. These findings demonstrate the important role motivated reasoning plays in the interpretation and application of messages discussing scientific issues and calls into question the traditional deficit model of science communication.

Analysis 1, which focused on the interaction between party affiliation and social identification may influence policy support, demonstrated that compared with offering no message(the control group), climate change messages, especially those talking about impacts on socially distant groups, are likely to amplify polarization about the issue. Probing of the role of identification with victims of climate change through the moderated-mediation model in Analysis 2 found that both H1 and H2 were supported: the effect of message exposure on identification with victims was contingent on political partisanship (H1) and identification with victims influenced policy support (H2).

The results indicate that message exposure activated motivated reasoning in participants, which increased polarization between Democrats and Republicans in policy preferences by causing polarization in identification with victims of climate change. Among Democrats, exposure to messages that contained either low or high social distance cues increased support for climate mitigation. At the same time, support for climate mitigation among Republican participants exposed to messages with low social distance cues were unmoved in their support for climate mitigation compared with control while exposure to messages with high social distance cues resulted in decreased support among Republicans for climate mitigation policy….

…these findings have important implications for science communicators and our understanding of how media coverage of climate change is likely to influence public opinion. As previously mentioned, Mutz (2008) asserts that exposure to media messages,regardless of the source, about contentious issues such as climate change is likely to activate political predispositions and increase political polarization about the issue due to the activation of biased information processes among audiences. Our study’s findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that political polarization increases significantly after message exposure (Hamilton, 2011; Hamilton & Keim, 2009; Hamilton et al.,2010; see Figure 2).

Furthermore, as climate change is a global phenomena, news stories often highlight the impact that climate change is having and will likely have in the future on different parts of the world. While media messages are often created with an informational, rather than persuasive intent, our results suggest that broad public exposure to news stories discussing the impacts of climate change on other groups outside the United States (e.g., Chhibber & Schild, 2009; Mydans, 2009) is likely to amplify the partisan divide on climate mitigation policies as motivated reasoning drives political polarization in identification with those affected by climate change….

…In addition, this study suggests that when creating general messages for the public, science communicators and environmental organizations can lower the risk of creating a boomerang effect among conservative segments of the population by focusing on local effects and including implications for local areas when discussing the impact that climate change may be having on distant populations. The adoption of this practice is uncertain, as generating localized coverage requires additional resources by newspapers or advocacy organizations to conduct area-specific research and to limit coverage to the area of impact. Failure to adopt this recommendation, however, is likely to deepen the gap between Republicans and Democrats on climate change…

Citation:

Hart, P., & Nisbet, E. (2011). Boomerang Effects in Science Communication: How Motivated Reasoning and Identity Cues Amplify Opinion Polarization About Climate Mitigation Policies Communication Research DOI: 10.1177/0093650211416646

Abstract:

The deficit-model of science communication assumes increased communication about science issues will move public consensus toward scientific consensus. However, in the case of climate change, public polarization about the issue has increased in recent years,not diminished. In this study, we draw from theories of motivated reasoning, social identity,and persuasion to examine how science-based messages may increase public polarization on controversial science issues such as climate change. Exposing 240 adults to simulated news stories about possible climate change health impacts on different groups, we found the influence of identification with potential victims was contingent on participants’ political partisanship. This partisanship increased the degree of political polarization on support for climate mitigation policies and resulted in a boomerang effect among Republican participants. Implications for understanding the role of motivated reasoning within the context of science communication are discussed.

See Also:

Communicating About Climate Risks While Avoiding Dire Messaging

Al Gore Seeks to Re-energize His Base with The Climate Reality Project

Peak Oil Perceptions: How Americans View the Risks of a Major Spike in Oil Prices

Study: Re-Framing Climate Change as a Public Health Issue

Report on Conveying the Public Health Implications of Climate Change