Elizabeth And Hazel Story Humanizes Little Rock Nine Icon

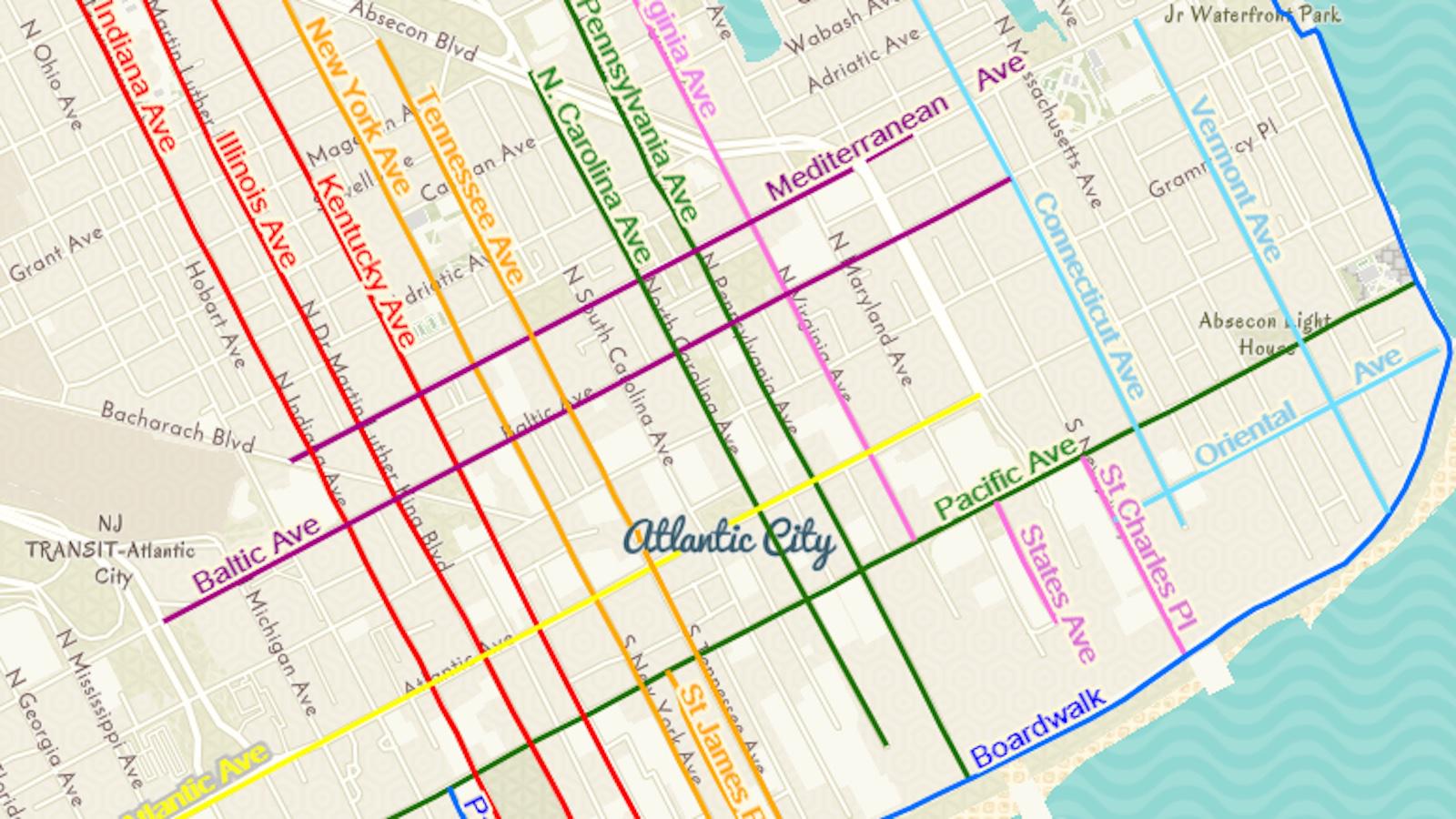

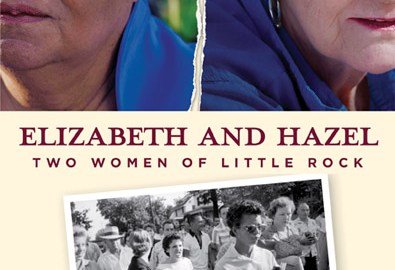

“Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate!” The black and white picture from the fifties of a teenaged white girl yelling racial epithets at a young black coed who marches through an angry white mob to desegregate a Deep South high school in 1957 is world famous.

“I walked South on Park Street toward 14th Street until I got in front of the school. I walked across the street and started to go up on the sidewalk. About 12 members of the National Guard stood in front of the school along the sidewalk on the West side of Park Street. As I stepped from the street to go toward the sidewalk the National Guardsmen stood in front of me and would not let me pass them.

They held their rifles in front of them but did not point them at me. I tried once to walk around them and as I did they moved to the side in front of me and would not let me pass. They did not say anything to me and I did not say anything. I then walked back across Park Street to the East side and walked South again to the corner of 16th and Park Streets where I sat down on a bench.

I want to say there were white people all along the East side of Park Street as I walked along, and they moved along with me as I walked. Some of them followed me closely also.”

Not much was known about Elizabeth Eckford, a member of the Little Rock Nine, as the pioneering African American students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas came to be known. Even less was known about Hazel Bryan, the young white girl who personified to the rest of the world all that was wrong with the South. Elizabeth And Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock by David Margolick attempts to fill in the blanks and tell us what has happened to these two women through the years.

After giving the reader a sense of the different worlds Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan inhabited in segregated Little Rock, Margolick’s account uses the familiar elements of this story—Brown vs. Board of Education, Daisy Bates, Central High, and the arrival of the 101st Airborne Division—as a springboard into the rest of the lives of these two women after the famous photograph is snapped by photographer Will Counts.

Elizabeth and Hazel humanizes the civil rights movement by chronicling the life of a key figure in the school desegregation fight. There is a trace of the style Margolick uses in his Vanity Fair articles in the first few chapters that do not fit the tone of the subject, but once he gets going in earnest, he does a pretty good job of letting the story tell itself. After wandering through several colleges and enduring a stint in the Army, Elizabeth Eckford has a tough time for the next three decades, raising two boys on her own while battling psychological demons.

The psychological horror of Elizabeth Eckford’s experiences at Central High, and her subsequent inability to cope with many of the challenges that come with trying to fit into the machinations of a modern day society shaped not only her life, but the lives of her children. Hazel Bryan, who recognizes herself in the famous photo soon after it is first published, gets married young and becomes Hazel Bryan Massery, a farmer’s wife. Over the years the Massery family prospers and Hazel’s attitudes change, leading her to see her fellow African American citizens in a different light.

Where this book really shines, and why I think you should read it, is when Margolick chronicles the reconnection of Elizabeth and Hazel in their later years and their on again, off again relationship. With a minimum of moralizing, Margolick shows the reader why racial reconciliation is more difficult in practice than in theory, especially for those who lived through some of the worst moments in our racial history.

What do African Americans have to give up, even today, in order to gain the ability to be seen as a normal, average, standard issue American? Do we have to participate in the denial, the way some Little Rock Nine members chronicled in the book seem to have done, to help white Americans retain a sense of psychological wholesomeness? Do we have to contradict those heinous wrongs some of us have seen with our own eyes and those bloody wounds some of us have bound with our own hands to allow white America to preserve its sense of righteousness?

I don’t think David Margolick discovered any definitive answers to these kinds of questions in Elizabeth and Hazel, but I certainly thank him for trying.