Did the Iconic Civil Rights Era Photographs Do More Harm than Good?

Now the stuff of history books, the iconic photographs of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States were once front-page news: snarling dogs, baton-wielding police, high-pressure fire hoses, and more used to keep African-American men, women, and children from realizing the promise of the American dream. White Northerners saw such images and pushed for legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to aid African Americans, bringing to an end that sad chapter of American history. Or so the story goes. In Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography, Martin A. Berger argues that the story in the history books isn’t true. Instead, Berger believes, those images portrayed African-Americans as weak and incapable of saving themselves—a portrayal that continues to prevent true equality and plagues race relations to this day.

“With great consistency,” Berger writes, “white media outlets in the North published photographs throughout the 1960s that reduced the complex social dynamics of the civil rights movement to easily digested narratives, prominent among them white-on-black violence.” African-American media, selecting from the same pool of possible pictures, presented a different narrative, but one that never took hold in the mainstream. The idea that Martin Luther King, Jr. and others were active agents in the pursuit of freedom threatened the white majority. “In order to safely move whites to either tolerate or embrace social and legislative change,” Berger concludes, “the photographs occluded various racial facts, including the agency of blacks in shaping American history and the shared beliefs of reactionary and progressive whites.” The small steps of the sixties towards equality came always on the terms allowed by whites. Such incremental improvements permitted “the unspoken assumptions of whites” about nonwhites to continue and still “keep large numbers of nonwhites from participating equally in society today,” Berger argues controversially. It’s hard to believe that nearly half-century-old images can still hold such power today, but Berger makes a persuasive case.

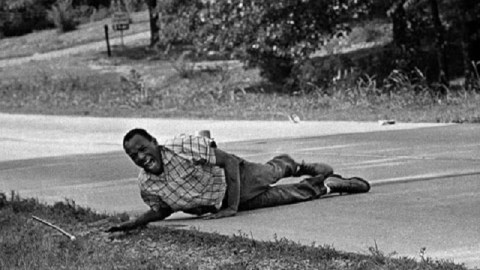

Seeing through Race excels when Berger, Professor and Director of the Visual Studies Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, puts specific images and their use in the media under his microscope. By placing cropped and uncropped versions of a photograph side by side, Berger shows the editorial decisions that, either consciously or unconsciously, depicted African-Americans as less powerful than whites. Berger refuses to condemn such decisions, which may have been done with the good intentions of bringing some improvements to the poor race relations of the day. Such people hoped to present African Americans as “perfect victims with imperfect tactics,” in Berger’s phrase—passive, nonviolent resisters with hearts of gold too naïve (or unintelligent, perhaps) to realize that Gandhi and King were wrong and would only lead them to the grave, unless someone came to their rescue. For example, James Meredith, the first African American to go to the segregated University of Mississippi wasn’t seen standing tall and challenging the system. Instead, Jack Thornell’s photograph of Meredith sprawled on the ground, felled by a shotgun blast while leading a voting rights march, became the iconic view of his story. Vulnerable rather than powerful, Meredith seems to reach out for help—a help that whites were more willing to give to the weak than those strong enough to threaten the status quo.

As a counterforce to this phenomenon, Berger resurrects the “lost” photos of the Civil Rights Movement, such as African-American athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith atop the Olympic medal stand in 1968 flashing the Black Power salute or Huey P. Newton of the Black Panthers sitting kinglike on a African throne while brandishing both a rifle and a spear. Berger breaks the “ugliness” barrier set by the white media by showing graphic photos of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old boy brutally murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman. At the time, Jet and other African-American publications showed the pictures, which Till’s mother wanted the world to see and thus allowed the open casket. Looking upon the face of Till, you come to believe Berger’s argument that certain limits were set in the narrative of the Civil Rights that bore little resemblance to the no holds barred reality.

Reading Berger’s approach reminded me of James Baldwin‘s 1949 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” his aesthetic and moral evisceration of Harriet Beecher Stowe‘s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Whereas Abraham Lincoln once lauded Stowe as “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war,” Baldwin saw not only poor writing in Stowe’s two-dimensional characters, but also a falsity that obscurity real truths about African-Americans and how whites really thought about them. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became “everybody’s protest novel” because it played to white preconceptions about race and rocked the boat gently, if it rocked it at all. Similarly, Berger suggests that the familiar Civil Rights era photos are now “everybody’s protest photography” for a similar kind of false sense of progress they offer.

“Truth [is]… a devotion to the human being, his freedom and fulfillment; freedom which cannot be legislated, fulfillment which cannot be charted,” Baldwin wrote in that essay. “[I]t is not to be confused with a devotion to Humanity which is too easily equated with a devotion to a Cause; and Causes, as we know, are notoriously bloodthirsty.” In Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography, Martin A. Berger thirsts for that same kind of truth—one obscured by the abstract “Humanity” and bloodthirsty “Cause” embedded in the images of that time that have echoed visually to our own. The election of Barack Obama as President simultaneously demonstrated how far America has come and how much further we must go in terms of race relations. Berger’s Seeing through Race looks back at the images of the past to give us a new vision of equality for the future.

[Image:Jack Thornell. James Meredith, wounded by a shotgun blast, sprawled on a highway near Hernando, Mississippi, June 6, 1966.]

[Many thanks to the University of California Press for providing me with a review copy of Martin A. Berger’s Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography.]