Can Lee Miller Ever Be More than Man Ray’s Muse?

“I don’t have students,” Man Ray allegedly told Lee Miller when she finally tracked the Surrealist down in a Parisian bar after he eluded her visit to his front door looking for tutelage. Miller became Man Ray’s student, then his lover, then his muse, and, eventually, as Man Ray/Lee Miller, Partners in Surrealism, a new exhibit at the Peabody Essex Museum, argues, his equal partner. A victim of her own beauty (her husband, artist Roland Penrose, compared meeting Lee for the first time to being “struck by lightning”), Miller continues to toil under the label of “muse” that diminishes her own artistry. This exhibition lifts that label and strikes you with the lightning bolt of realization that Miller and Man Ray developed a deep, profound relationship on multiple levels—artistic, emotional, and philosophical—that we’re still trying to understand.

“For the Surrealists,… objects were more than raw, often vernacular materials to be played with or artworks in and of themselves” Lynda Roscoe Hartigan writes in the exhibition catalog, “they were also material evidence of the artist’s culture—his or her milieu of thought processes and creativity.” Lee Miller knew what it was to be an object and to use objects in this way. Man Ray and other artists, including even Picasso, objectified Miller for her beauty at the same time that Lee herself used photographs to assert her individuality and independence. For Man Ray, for whom “people and objects held equal weight for him as ‘things’”, Hartigan believes, “Lee Miller was the exception, her presence and absence a catalyst of poignantly obsessive proportions.”

Man Ray’s magnificent obsession drove him to include Miller in his life and his art, but also drove his impulse to keep her in his control. “When it came to women’s rights, the Surrealists talked a good game, but failed to deliver on their promises,” Phillip Prodger, curator of photography at the Peabody Essex Museum, points out in the catalog. Although the Surrealists professed a disdain for all social conventions, when it came to sexual freedom, they saved that freedom for themselves and forbade it for their “muses.” Miller’s promiscuity (with Jean Cocteau and others) maddened Man Ray. Despite that sexual tension, however, Miller and Man Ray achieved a partnership of equality when it came to art. In many instances, Prodger argues, “the two were experimenting with the same idea, and authorship appears to have fallen to whoever happened to be operating the camera at the time of exposure.” True partners, Lee and Man cared more about the art than about who got credit, resulting in a muddle that still plagues Miller’s reputation today.

Despite an increasing number of exhibitions of Lee Miller’s art (spearheaded by her son, Anthony Penrose, who contributes a heartfelt memorial to his mother in the catalog), Miller remains Man Ray’s muse. “Considering her fierce antipathy to the chauvinism of her day,” Prodger considers, “it is surprising that she continues to be described in such a belittling fashion.” Miller left Man Ray in 1932 precisely to escape the “muse” trap. Yet, the label lingers on. Works such as Man Ray’s A l’heure de l’observatoire–les amoureux (in English, Observatory Time–The Lovers; shown above) capture the nature of this captivity of Miller’s reputation. Man Ray claimed that he worked on the painting for an hour or two each morning while still in his pajamas for two years, a story that, even if false, at least indicates the obsessive nature of the image. In the painting, Miller’s disembodied lips levitate over a landscape punctuated by the Montmartre observatory Man Ray could see from his studio. Even when not physically present, Miller’s psychological presence continued to hover over Man Ray’s art—the muse who paradoxically refused to stay and to leave.

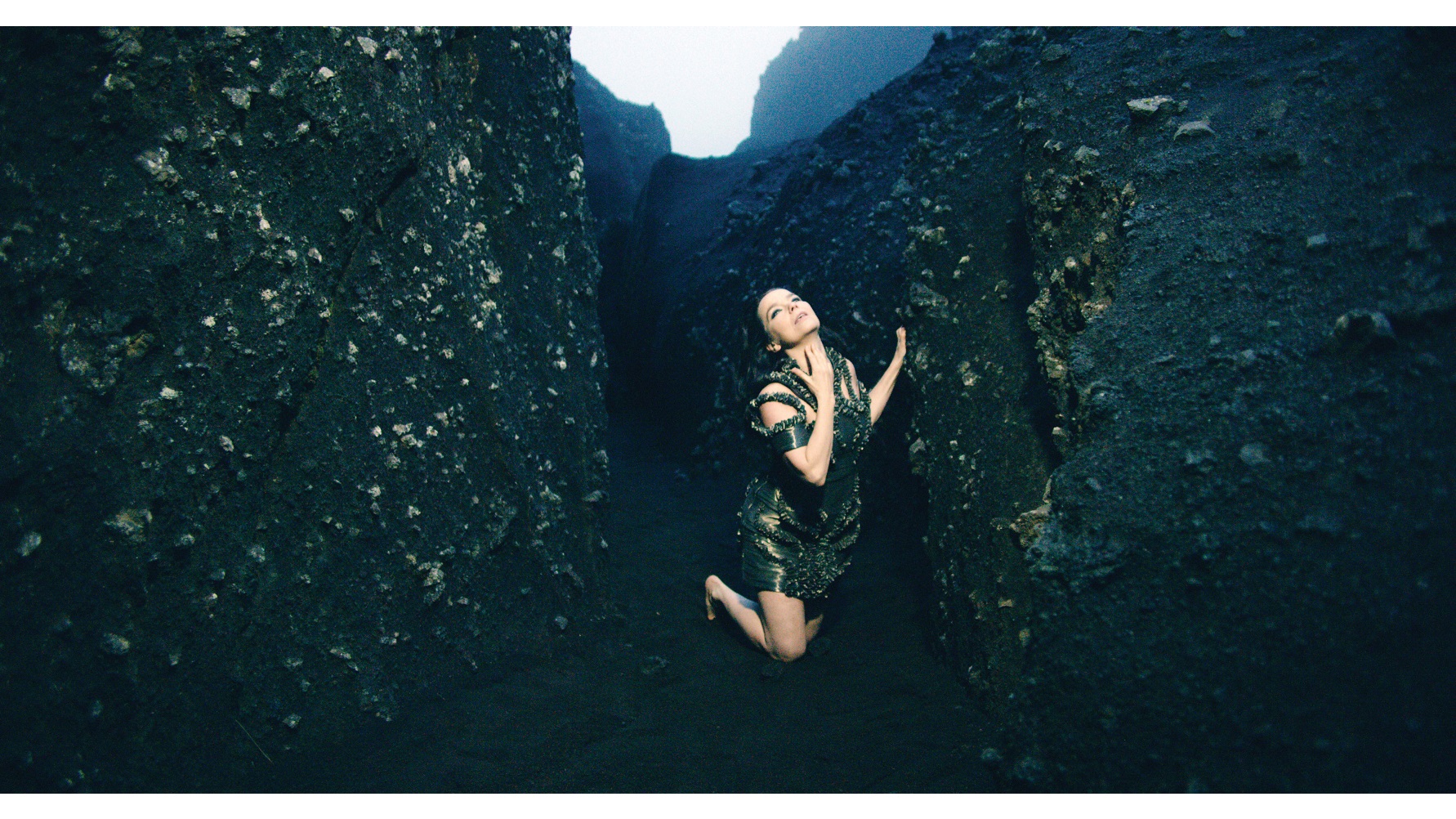

Prodger compiles a remarkable analysis of the differences between the photography of Miller and Man Ray that helps define the partnership as mutual rather than “muse”-ual. Whereas Man Ray’s nude photography of Lee showed her as “sensual, vulnerable, and alluring,” Prodger writes, Miller’s nude self-portraits portray her as “formidable: her muscles have definition, determination is written on her face, and her spine is stiffened. Seen through her own lens, Miller is a bold, feminist hero.” The objectified Miller transformed herself into an object that fought back, defying sexist labels using the very same genre conventions that men used to limit her.

Rather than paint Man Ray as a villain, however, the exhibition strives to keep the unique relationship between him and Miller true to real life. Miller’s troubled childhood, followed by her wartime experiences (including seeing the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps in person), scarred her psyche to the point that she essentially stopped working as an artist by 1953. Roland Penrose and Lee purchased works by Man Ray when he struggled financially, and he later reciprocated with artistic gifts he hoped would solace Lee’s troubled soul. Anthony Penrose’s piece captures the lasting affection and respect between the two former lovers and artistic experimenters. In 1974, two years before his own death, Man Ray created a “consoler” for Lee from a wooden cigar box to which he had added a fish-eye lens placed in a drilled peephole. “I think what Man meant,” Anthony offers, “was that if she didn’t like what she saw in her life, peeping through the lens of his Consoler might give her troubles a different perspective and help her get through them.”

Man Ray/Lee Miller, Partners in Surrealism acts as a consoler for those who continue to suffer under sexist labels as artists. It is a lens through which we can look at the art of Man Ray and Lee Miller and see not a master and muse but two modern art masters working together and challenging one another to greater and greater creativity. Alas, Man Ray’s desire for a “muse” overpowered his desire for a colleague until it was too late to keep Miller the artist, if not Miller the lover, in his life. When the women artists of today don’t like what they see in their life, they should look to Man Ray/Lee Miller, Partners in Surrealism and trust that things are changing for the better.

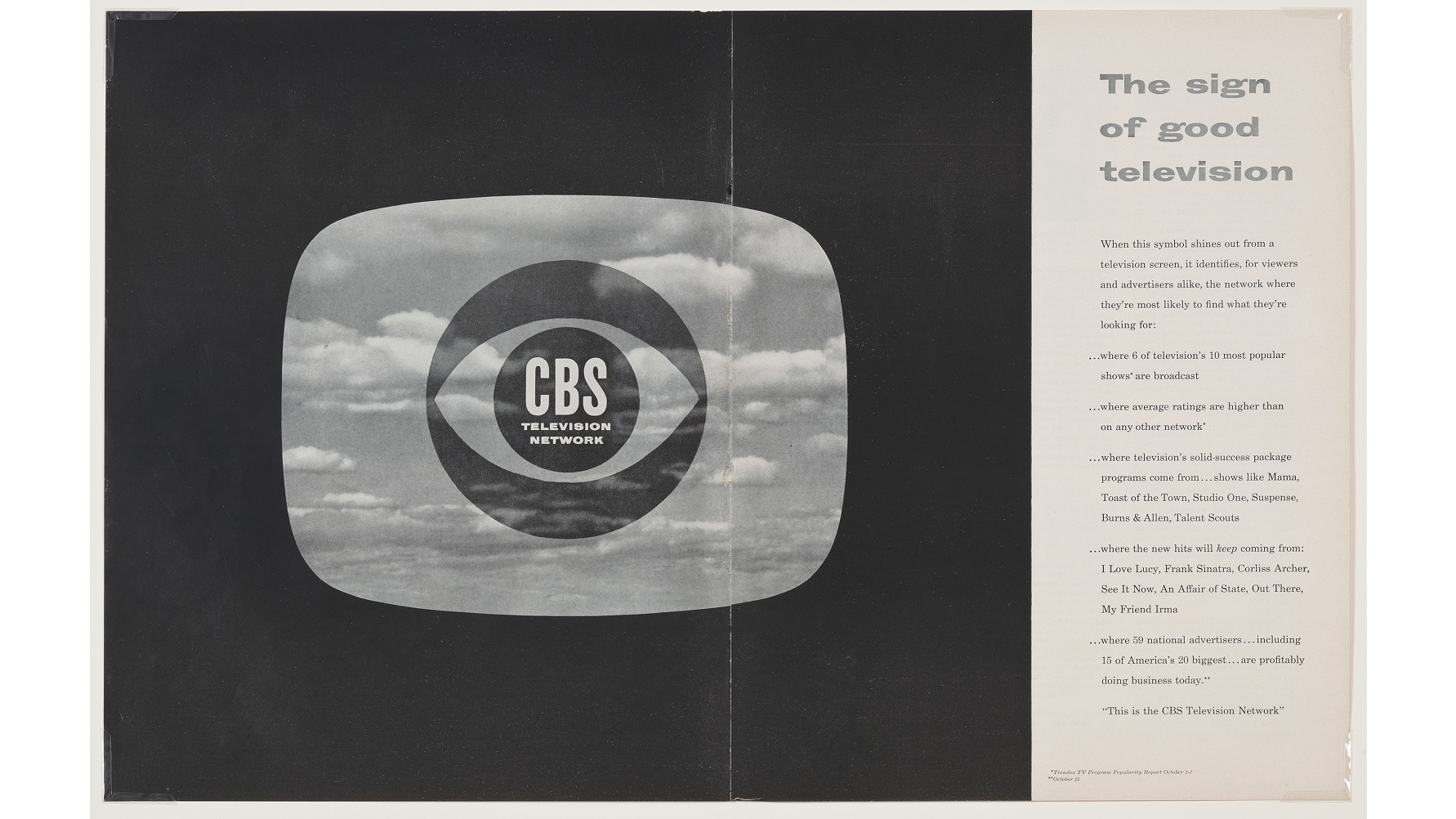

[Image:Man Ray (1890–1976); A l’heure de l’observatoire–les amoureux (Observatory Time–The Lovers), 1964, after a canvas of c.1931; Color photograph; 19 5/8 x 48 3/4 in. (50 x 124 cm); The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; © 2011 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris/ Photo © The Israel Museum by Avshalom Avital.]

[Many thanks to the Peabody Essex Museum for providing me with a review copy of the catalog and other press materials related to Man Ray/Lee Miller, Partners in Surrealism, which runs through December 4, 2011.]