Can scientists find the ‘holy grail’ of Alzheimer’s research?

Credit: Adobe Stock

- Alzheimer’s is a neurodegenerative disease that is estimated to affect twice as many Americans by 2050, making it a troubling eventuality for many young adults.

- There’s currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, but clinical trials of immunotherapy approaches show promise.

- Immunotherapies may also alleviate the psychotic symptoms of Alzheimer’s, like agitation, aggression, and paranoia.

It can be hard to conceptualize the total damage caused by Alzheimer’s. The neurodegenerative disease is a leading cause of death in the U.S., killing more than 100,000 people each year. And as Alzheimer’s progresses in the brain it not only erodes memory but also causes troubling symptoms like agitation, paranoia, and aggression.

These burdens fall not only on patients but also on their loved ones, doctors, and caregivers. Economically, the cost of caring for Alzheimer’s patients hit an estimated $305 billion in 2020, according to a report from the Alzheimer’s Association. And that figure doesn’t include an estimated $244 billion in unpaid caregiving provided by family and friends.

The number of Alzheimer’s patients in the U.S. is expected to double by 2050, affecting about 14 million people. That’s one reason why hospitals and health professionals are already working to bolster how they care for the elderly and Alzheimer’s patients. It takes 15 years to develop new treatments, so today’s research needs adequate funding.

“Caring for our older adults is a big responsibility, one that we take great pride in,” said Michael Dowling, president and CEO of Northwell Health. “Our aging population will face health issues, including and especially Alzheimer’s, that will require the right care at the right time. That’s why we have increased our services, including at Glen Cove Hospital, and research at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research.”

… the real suffering comes from the changes that happen in the personality…

While the costs of Alzheimer’s are clear, its exact causes remain frustratingly mysterious. Currently, there’s no cure for the disease, nor treatments that stop its progression.

“Alzheimer’s is this brain problem, and everyone sort of knows what’s probably causing the problem, but nobody’s been able to do anything about it,” said Dr. Jeremy Koppel, a geriatric psychiatrist and co-director of the Litwin-Zucker Alzheimer Research Center.

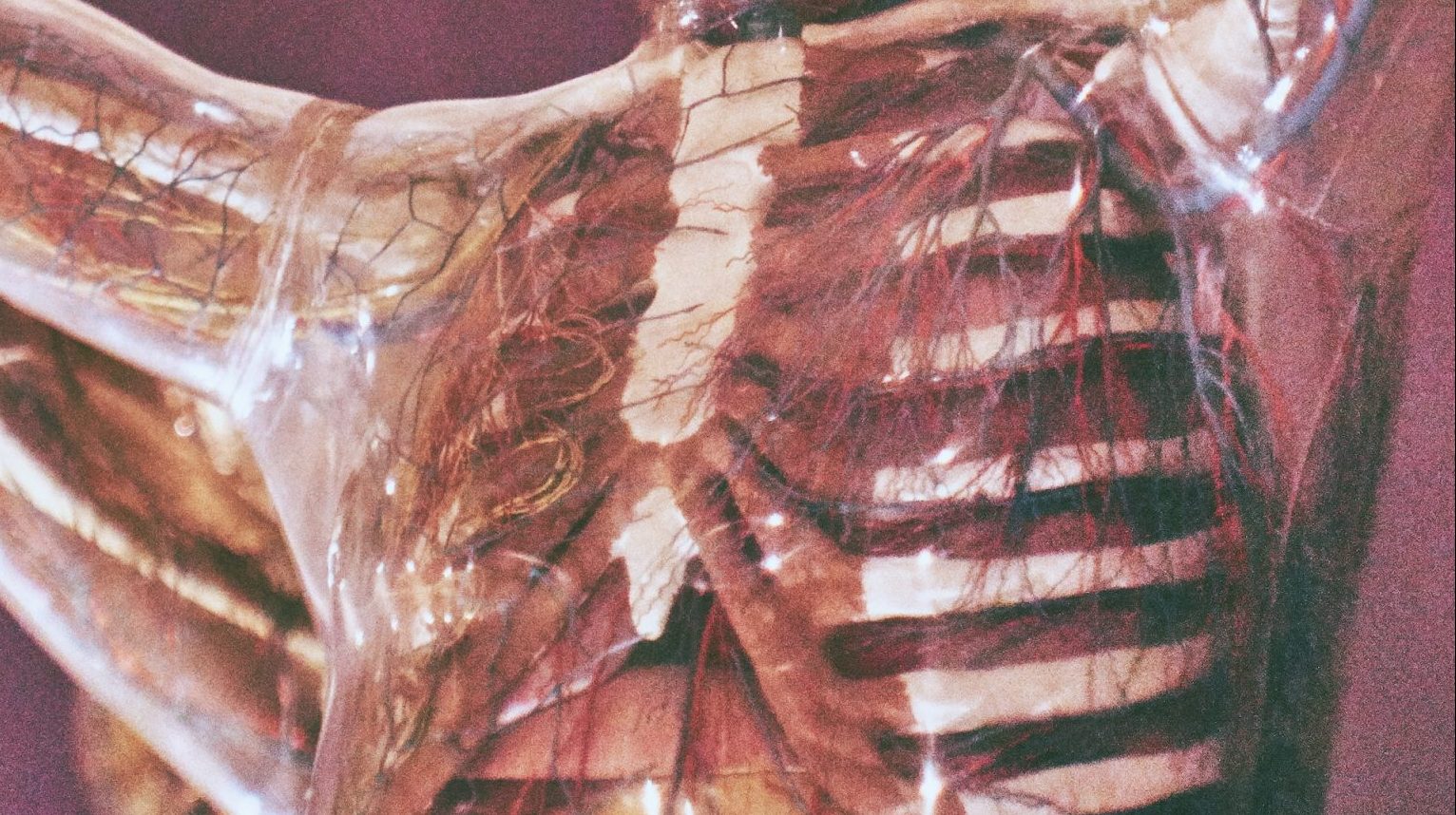

But in recent decades, researchers have zeroed in on likely contributors to the disease. The brains of Alzheimer’s patients reliably show two abnormalities: build-ups of proteins called abnormal tau and beta-amyloid. As these proteins accumulate in the brain, they disrupt healthy communication between neurons. Over time, neurons get injured and die, and brain tissue shrinks.

Still, it’s unclear exactly how these proteins, or other factors such as inflammation, may drive Alzheimer’s.

“We are dealing with very complicated components,” said Dr. Philippe Marambaud, a professor at the Feinstein Institutes and co-director of the Litwin-Zucker Alzheimer Research Center. “The actual culprit is not clearly defined. We know there are three possible culprits [tau, beta-amyloid, inflammation]. They’re working in concert, or maybe in isolation. We don’t know precisely.”

Many Alzheimer’s researchers have spent years developing therapies that target beta-amyloid, which can accumulate to form plaques in the brain. The Alzheimer’s Association writes:

“According to the amyloid hypothesis, these stages of beta-amyloid aggregation disrupt cell-to-cell communication and activate immune cells. These immune cells trigger inflammation. Ultimately, the brain cells are destroyed.”

Unfortunately, clinical trials of therapies that target beta-amyloid haven’t been effective in treating Alzheimer’s.

In brains with Alzheimer’s disease, tau proteins lose their structure and form neurofibrillary tangles that block communication between synapses.Credit: Adobe Stock

At the Feinstein Institutes, Dr. Marambaud and his colleagues have been focusing on the lesser-explored Alzheimer’s component: abnormal tau.

In healthy brains, tau plays several important functions, including stabilizing internal microtubules in neurons. But in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, a process called phosphorylation changes the structure of tau proteins. This blocks synaptic communication.

Dr. Marambaud said there are good reasons to think anti-tau therapies may effectively treat Alzheimer’s.

“The main argument around why [anti-tau therapies] could be more beneficial is that we’ve known for a very long time that tau pathology in the brain of the Alzheimer’s patient correlates much better with the disease progression, and the loss of neuronal material in the brain,” compared to beta-amyloid, Dr. Marambaud said.

“The second strong argument is that there are inherited dementias, called tauopathies, which are caused by mutations in the gene coding for the tau protein. So, there is a direct genetic link between dementia and tau pathology.”

To better understand how this protein interacts with Alzheimer’s, Dr. Marambaud and his colleagues have been developing immunotherapies that target abnormal tau.

Immunotherapies, such as vaccines, typically target infectious diseases. But it’s also possible to use the body’s immune system to prevent or treat some non-infectious diseases. Scientists have recently succeeded in treating certain forms of cancer with immunotherapies, for example.

“We have developed a series of monoclonal antibodies, which are basically the therapeutics that are required when you want to do immunotherapy,” Dr. Marambaud said.

Vaccine revolution: Curing Alzheimer’s from the inside | Lou Reese | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

Currently, Feinstein Institutes researchers are conducting promising ongoing clinical trials with anti-tau antibodies, some of which are in phase III trials under the Food and Drug Administration. Patients receive these therapies intravenously over several hours and would undergo multiple rounds of treatment. It’s similar to chemotherapy.

In the short term, it’s more likely that anti-tau therapies would help to stabilize Alzheimer’s, not cure it.

“Just stabilization of the disease’s progression will save a huge societal, but also financial, burden,” Dr. Marambaud said. “As research progresses, we would improve upon these stabilization approaches to make them more and more efficacious.”

Even if anti-tau therapies don’t prove to be the holy grail of Alzheimer’s treatments, they could potentially alleviate severe behavioral symptoms of the disease, and potentially illuminate some of the mechanisms behind psychosis.

Credit: Getty Images

When most people think of Alzheimer’s, they tend to focus on the erosion of memory. But the darkest effects of the disease are often psychotic symptoms like agitation, aggression and paranoia, according to Dr. Koppel, who, in addition to researching Alzheimer’s, spent decades treating Alzheimer’s patients as a clinician.

“My research focus comes out of 20 years of sitting with Alzheimer’s families and listening to what the primary issue is,” said Dr. Koppel. “It’s never memory. It starts out with memory as a diagnostic issue. But the real suffering comes from the changes that happen in the personality and the belief system that make Alzheimer’s patients” ostracized or even become violent toward their loved ones.

At the Feinstein Institutes, Dr. Koppel’s research focuses on alleviating Alzheimer’s-related psychotic symptoms through anti-tau immunotherapies.

“It’s our hypothesis that abnormal tau proteins in the brain somehow, downstream, impact the way that people think,” Dr. Koppel said. “And the impact that it has is this paranoid, agitated, psychotic phenotype.”

Supporting this hypothesis is research on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative disease that involves the accumulation of abnormal tau. CTE, common among professional football players, also causes psychotic symptoms like agitation, aggression and paranoia.

What’s more, research shows that as Alzheimer’s patients accumulate more abnormal tau in their brains, as measured through cerebrospinal fluid, they exhibit more psychotic symptoms, and are more likely to die sooner than patients with less abnormal tau.

Given these strong connections between psychosis and abnormal tau, Dr. Koppel and his colleagues hope that anti-tau immunotherapies will alleviate psychosis in Alzheimer’s patients, who currently lack safe and effective treatment options and are often given medication that is meant to alleviate psychosis in people with schizophrenia.

“We are giving medications to Alzheimer’s patients that hasten their cognitive decline and lead to bad outcomes, like stroke and sudden death,” Dr. Koppel said. “Nonetheless, the schizophrenia medications do treat some of the psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior related to Alzheimer’s disease, and for many families this is crucial. We just don’t have many options, and we desperately need more.”

Beyond treating Alzheimer’s patients, anti-tau immunotherapies may shed light on other mental illnesses.

“Alzheimer’s may give us a window into what happens in the brain that makes people psychotic,” Dr. Koppel said. “Once you have a biologic treatment for psychosis that gets at an underlying pathophysiology, believe me, you could look at schizophrenia in new ways. Maybe it’s not going to be tau, but it may be a paradigm for treating mental illness.”

Dr. Marambaud said the long-term goal of anti-tau immunotherapies is to prevent Alzheimer’s. But that’s currently impossible because scientists lack the biomarkers and diagnostic tools needed to detect the disease before cognitive symptoms appear. It could take decades before prevention becomes possible, if it ever does.

In the short term, stabilizing Alzheimer’s is a more realistic goal.

“Our hope is that the treatments will be aggressive enough so that we can at least stabilize the disease in patients identified to be already affected by dementia, with cognitive tests that can be done by the clinicians,” Dr. Marambaud said. “And even better, maybe reduce the cognitive impairments.”

Dr. Marambaud said he encourages the public not to lose faith.

“Be patient. It’s a very complicated disease,” he said. “A lot of labs are really committed to making a difference. Congress has also realized that this is a huge priority. In the past five years, [National Institutes of Health] funding has increased tremendously. So the scientific field is working very hard. The politicians are behind us in funding this research. And it’s a complicated disease. But we will make a difference in the years to come.”

In the meantime, the Alzheimer’s Association notes that physical activity and a healthy diet can reduce the chances of developing Alzheimer’s, though more large-scale studies are needed to better understand how these factors interact with the disease.

“Many of these lifestyle changes have been shown to lower the risk of other diseases, like heart disease and diabetes, which have been linked to Alzheimer’s,” the association wrote. “With few drawbacks and plenty of known benefits, healthy lifestyle choices can improve your health and possibly protect your brain.”