3D printing might save your life one day. It’s transforming medicine and health care.

Northwell Health

- Medical professionals are currently using 3D printers to create prosthetics and patient-specific organ models that doctors can use to prepare for surgery.

- Eventually, scientists hope to print patient-specific organs that can be transplanted safely into the human body.

- Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health care provider, is pioneering 3D printing in medicine in three key ways.

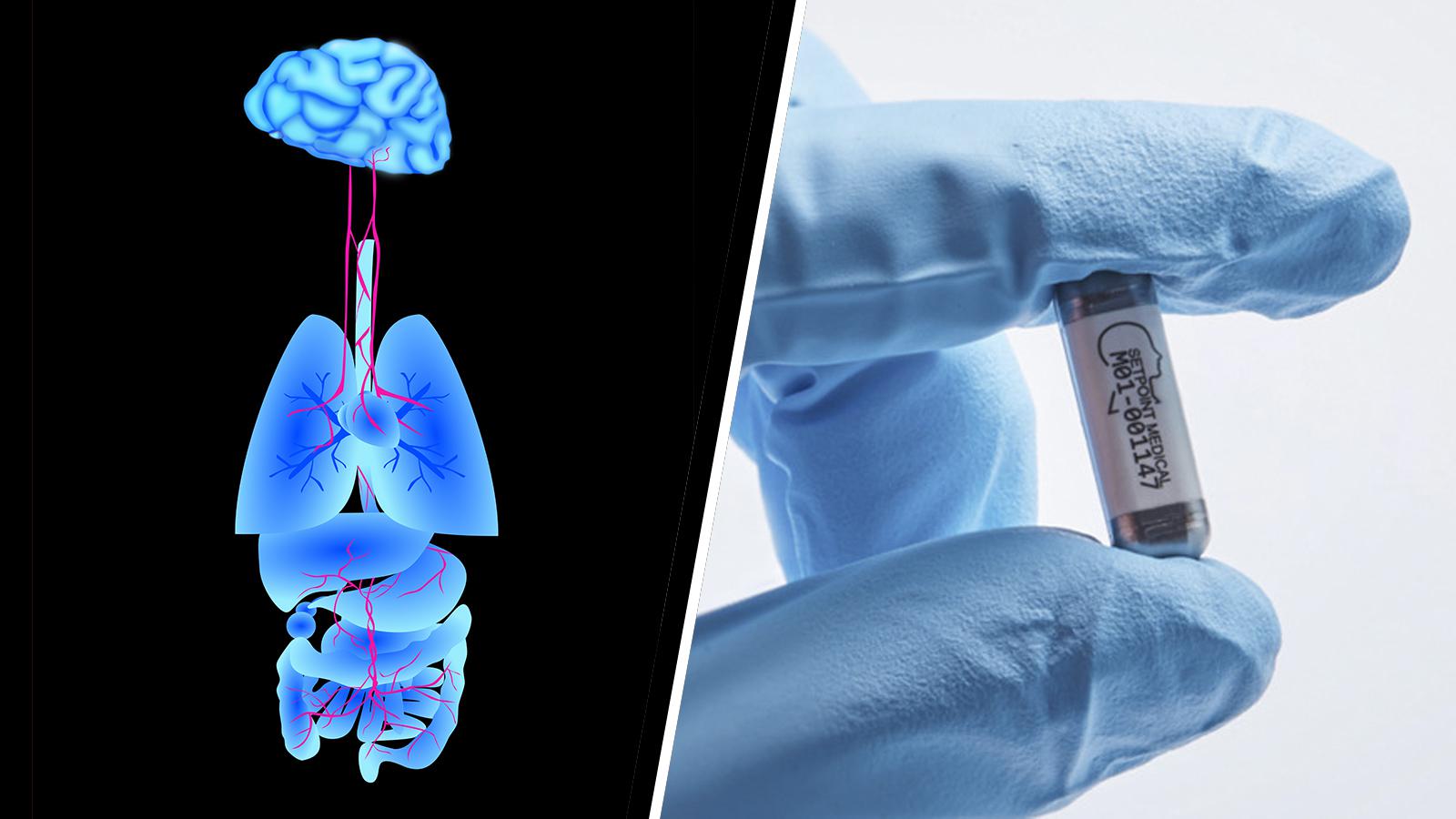

Imagine that a health emergency strikes and you need an organ transplant – say, a heart. You get your name on a transplant list, but you find out there’s a waiting period of six months. Tens of thousands of people find themselves in this dire situation every year. But 3D printing has the potential to change that forever.

The technology could usher in a future where transplantable organs can be printed not only cheaply, but also to the exact anatomical specifications of each individual patient.

What other innovations could 3D printing bring to medicine and health care? The sky is the limit, according to Dr. Todd Goldstein, a researcher with the corporate venturing arm of Northwell Health, New York State’s largest health care provider and an industry leader in 3D-printing research and development.

“It comes down to what people can think up and dream up what they want to use 3D printing for,” Goldstein says. “Ideally, you would hope that 50 years from now you’d have on-demand, 3D printing of organs.”

While that’s still on the horizon for researchers, 3D printing is already improving lives by revolutionizing medicine in three key areas.

3D printers can take images from MRI, PET, sonography or other technologies and convert them into life-size, three-dimensional models of patients’ organs. These models serve as hands-on visualization tools that help surgeons plan the best approaches for complex procedures.

They also allow doctors to customize patient-specific models prior to surgery. For example, Northwell employs 3D printing in several clinical applications:

- Tumor resection models clearly highlight the tumor and surrounding tissue

- Orthopedic models are useful for pre-surgery measuring and medical device adjustments

- Vascular models identify malformations in organs, tumors, sliced chambers, blood flow, valves, muscle tissue, and calcifications

- Dentistry oral implants and appliances can be created in just one day, significantly reducing wait periods for Northwell dentists and their patients

Using realistic models not only delivers better health results but also shortens operating times. That gives patients less time under anesthesia, and hospitals potential savings of millions of dollars over just a few years.

Being able to visualize procedures before they occur also helps to comfort patients and their families. Take, for instance, the case of Barnaby Goberdhan, a man who discovered that his young son, Isaiah, had an aggressive tumor in his palate. Goberdhan met with Neha A. Patel, MD, a pediatric otolaryngologist at Cohen Children’s Medical Center, a Northwell Health hospital, to discuss the procedure and learn about it with help from a 3D-printed model.

“Having a 3D printed depiction of my son was really helpful when talking with the doctor about his surgery,” said Mr. Goberdhan. “The doctor was able to do more than talk me through what they were going to do – Dr. Patel showed me. There is almost nothing more frightening and stressful than having your child go through surgery. There were several options Dr. Patel walked us through for the best way to preserve Isaiah’s teeth and prevent additional cuts within his mouth. I wanted all of my questions answered so I could be less fearful and more prepared to talk my son through what he was about to face. I wanted Isaiah to feel prepared. With the 3D model, we both felt more at ease.”

For years, 3D printing surgical models was prohibitively expensive. Now, more affordable systems such as Formlabs’ Form Cell give more hospitals across the country access to the technology in order to produce realistic, patient-specific models, usually within one day.

Credit: Northwell Health

While 3D-printed organs are a long way in the future, today’s technology is well suited for manufacturing prosthetics. 3D-printed prosthetics are often remarkably more affordable and personalized than their traditional counterparts. That’s a big deal for many families, especially those with children who outgrow prosthetics and are forced to buy new ones.

One recent breakthrough in 3D-printed prosthetics came when Dan Lasko, a former Marine who lost the lower part of his left leg in Afghanistan, wanted the ability to swim with his prosthetic leg. Wearing prosthetics in water has been possible for years, but they typically slow swimmers down. No device had been able to go seamlessly from land to water or to help propel its wearer through the water.

To fix that, Northwell Health recently funded a project that developed The Fin – the world’s first truly amphibious prosthetic. With The Fin, Lasko and his family can go straight into the pool from the locker room – or the diving board.

THE RETURN | NORTHWELL HEALTHyoutu.be

“I got back in the pool with my two young sons and for the first time was able to dive into the pool with them,” Lasko said.

3D-printed prosthetics will help improve the daily lives of the nearly 2 million Americans who’ve lost a limb. That’s promising because the increasing prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is expected to greatly increase the number of amputees in the U.S., according to a study published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

For years, 3D printers have manufactured various products: phone cases, toys, and even operational guns. To produce these objects, the machines heat a raw material, typically plastic, and build the object layer-by-layer according to a particular design.

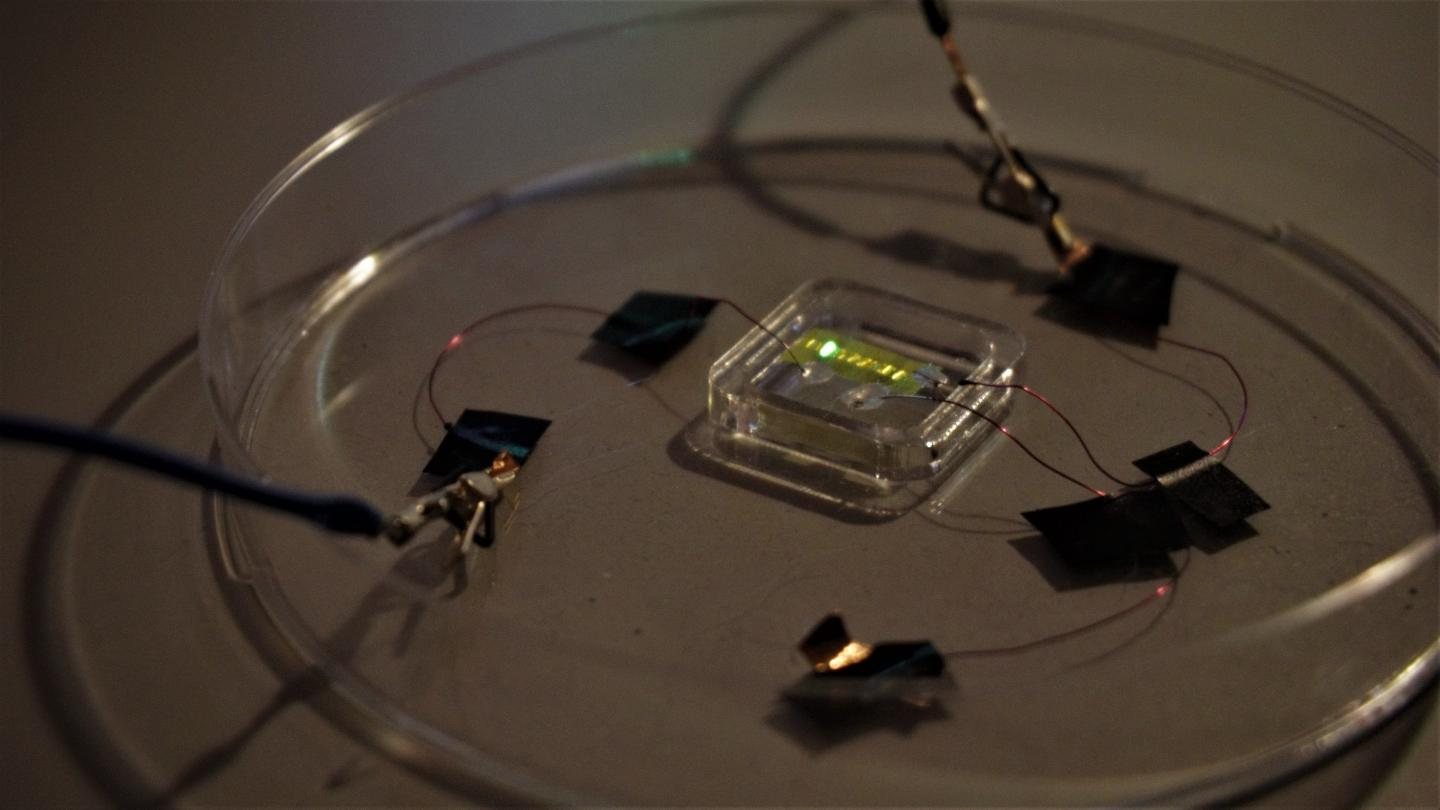

3D bioprinting, a young field developed by researchers with Northwell Health, may someday perform the same process but instead with living cells in a raw material called bioink.

Daniel A. Grande, director at the Orthopedic Research Laboratory in the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, an arm of Northwell Health, said he and his team first pursued 3D bioprinting by modifying 3D printers so they’d accept living cells.

“My initial concept of 3D printing was early studies that looked at modifying ink-jet printers, where we incorporate a bioink that includes cells within a delivery vehicle,” Grande says. “That hydrogel can then be polymerized, or hardened, upon heat or UV-light stimulation, so that we can actually make a complex structure, three-dimensionally, that incorporates living cells. The hardened hydro-gel is then able to keep the cells alive and viable. It’s also biocompatible, so it can be safely implanted in humans.”

It’s a promising enterprise, and it can radically change how we experience medical care.

“3D bioprinting’s potential is almost limitless and has the potential to replace many different parts of the human body,” says Michael Dowling, president and CEO at Northwell Health, and author of Health Care Reboot. “Researchers envision a future with 3D printers in every emergency room, where doctors are able to print emergency implants of organs and bones on demand and revolutionize the way medicine is practiced.”

Dr. Todd Goldstein explains more about 3D bioprinting below:

3D Bioprinting (60 sec)youtu.be