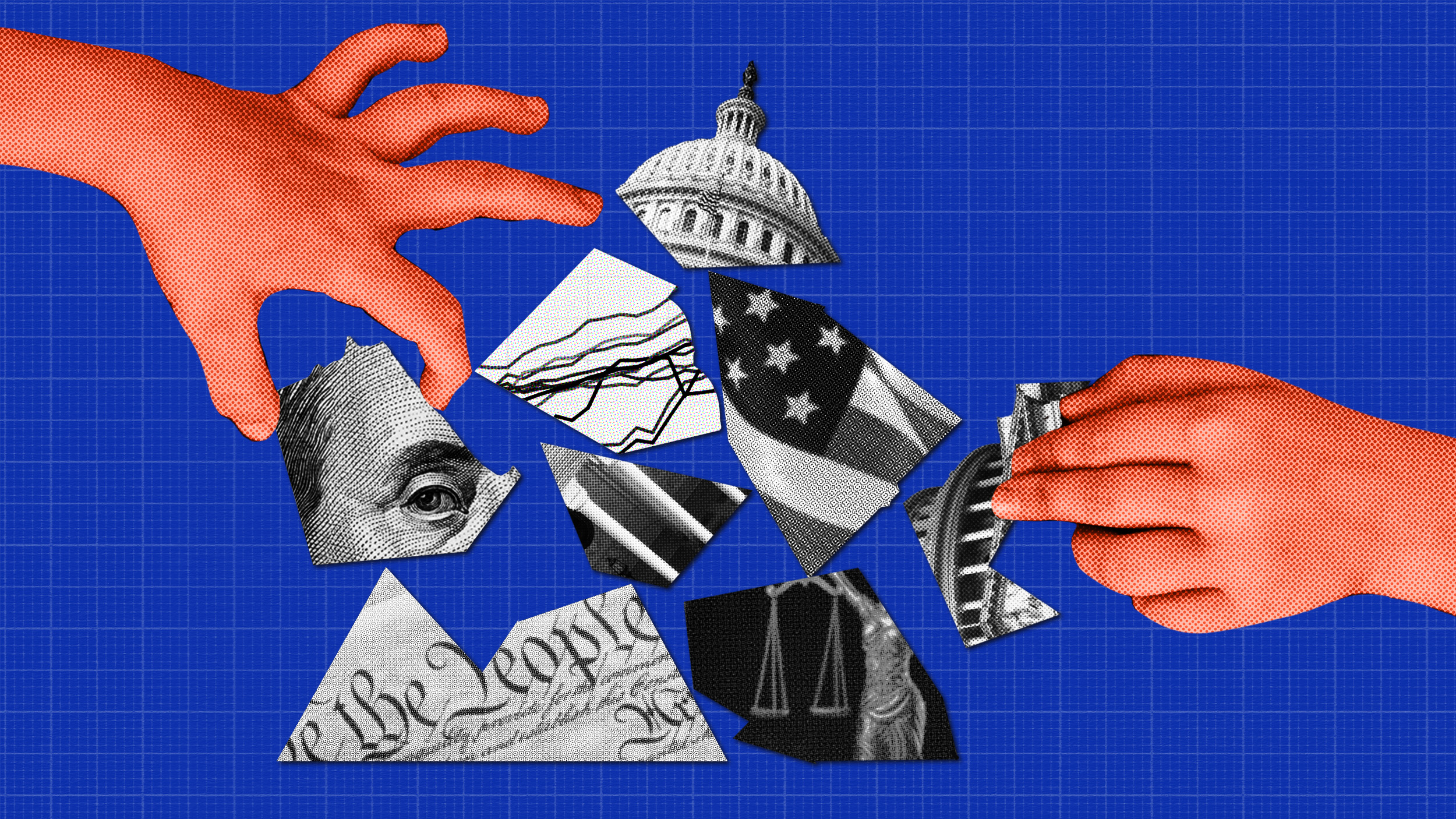

Could the Tea Party Movement Go Global?

What does the Tea Party Movement in the U.S. have in common with the right-wing backlash against immigrants in Europe? Bard College professor Ian Buruma says they are both part of “a general anxiety caused by globalization, by the influence of international corporations, of super-national organizations and so on. People feel that they’re in a world where they’ve lost their grip on who they are, where they belong. They don’t know who represents them anymore and so on. And this has led often to defensive reactions and often hostile reactions, partly against the political elites that are blamed for this state of affairs, that are blamed for these anxieties, but also against the alien elements.”

In his Big Think interview, Buruma talks at length about the cultural issues posed by immigration in Europe—and the growing right-wing backlash that is rising up in many countries against it. He says that it is possible that Muslim immigrants in Europe might create political parties to ensure their rights, but notes that “there is no such thing as an Islamic community. They are very divided. They come from very different cultures. There is a schism between the Shiites and the Sunnis and so on, so it is difficult for Muslims to make a common political cause.”

Buruma doesn’t think that the division between church and state in the U.S. is going to crumble anytime soon, but he notes that the country has always been challenged by conservative Christians who accuse secular lawmakers of being in cahoots with the devil. By the same token, many in the modern world see religion as a challenge to libralism and democracy. “In Europe people thought that this was a problem that had been successfully licked. But Islam is now seen as a challenge,” he says. “The mobilization of the religious right in the United States is seen as a challenge and there have been acts of religious-inspired violence in places like Japan.”

If the noted French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville were to see modern-day America, Buruma says, he’d likely be “shocked,” because some of his most pessimistic predictions have come true. Buruma notes that de Tocqueville was “frightened of the possible consequences” of democracy and “thought it could lead to tremendous vulgarity”—and imagines the philosopher wouldn’t approve of the tone of many of the less-than-high-minded public figures and politicians who lead us.