Saving Grace: Seeing Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic” Anew at the PMA

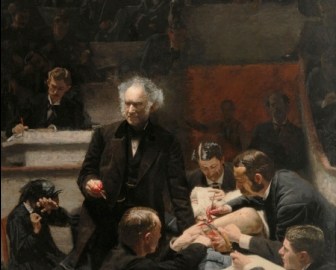

“[The painting is] one of the most powerful, horrible and yet fascinating pictures that has been painted anywhere in this century,” wrote the New York Tribune in 1879 of then 31-year-old Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic. “But the more one praises it, the more one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to look at it. For not to look at it is impossible.” Eakins’ masterpiece suffered the indignity of a jury’s rejection at the 1876 Centennial in his native Philadelphia, but in An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing The Gross Clinic Anew at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, that injustice is posthumously corrected by bringing back Eakins’ original artistic intentions after nearly a century of conservationist interventions. The savage grace of The Gross Clinic returns in the PMA’s saving efforts to restore Eakins’ sense of tone and atmosphere. How this iconic image of the brutal ballet of science and art fell into a twisted tango of aesthetic missteps over time serves as a cautionary tale as well as a hopeful one in its new restoration.

Eakins the young artist and Samuel Gross, the “Emperor of American Surgery,” crossed paths just as the artist took his first steps toward fame and the surgeon stood at the height of his renown. Hounded by Eakins to pose for more studies for the painting, Gross reportedly said, “Eakins, I wish you were dead.” The Gross Clinic gave Dr. Gross artistic immortality that outpaced his medical accomplishments, while launching Eakins into the ranks of American art fame, and infamy. Love it or hate it, as the New York Tribune said of the painting, you can’t take your eyes off of it. The jury of the 1876 Centennial art exhibition hated it, relegating the painting to the medical section, far from the eyes of the general public.

As Dr. Kathleen Foster, the curator of the exhibition, explained, this is a “remedial Centennial” for Eakins. Set among dark walls and red drapery in the PMA’s gallery space, The Gross Clinic finally enjoys the salon-type setting it was denied so long ago. Reunited with Eakins’ Portrait of Dr. Benjamin H. Rand, which the jury did accept for the Centennial, and with Eakins’ other “clinical” masterpiece, The Agnew Clinic, The Gross Clinic finally takes its rightful place. It’s a wonderful birthday present for the artist, who would have been 166 years old on the day on which the exhibit opens.

But even more important than the restoration of place is the restoration of tone and color of The Gross Clinic. Eakins’ painted The Gross Clinic during a time when low toned painting with dark, restrained color was in vogue. He would paint brilliant color underneath and then subdue it with dark varnishes to realize the overall effect he hoped for. In fact, in Eakins’ day, brilliant color was seen as vulgar. Alas, during the twentieth century, that vulgar color became all the rage. When early conservators rediscovered the brilliant colors beneath Eakins’ varnishes, they made the aesthetic choice to bring those colors out. In the process, they wrecked the balance of tones and often even the modeling of Eakins’ original work. Even the protestations of Eakins’ widow, Susan, fell on deaf ears.

The exhibition (and especially the wonderful accompanying video at the end of the gallery) focuses on how those aesthetic choices were made and how conservators today unmade them through meticulous detective work to determine exactly what the painting looked like in Eakins’ day and just how it changed over the years. To their credit, the PMA’s conservators refused to pass harsh judgment on their predecessors, knowing that each era makes its own aesthetic rules and they, too, may one day be judged.

For anyone who loves The Gross Clinic or Eakins, An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing The Gross Clinic Anew is a must see. As a native Philadelphian, I’ve seen the painting countless times, but I found myself nearly knocked over by the freshness and vitality that had been so long obscured. This is truly a masterpiece restored. From the actual scalpel used by Dr. Gross to “case studies” of other paintings by Eakins restored to his original intent, the PMA surrounds this newly polished jewel with the perfect setting. Perhaps the most encouraging and hopeful message to take from this exhibition is that museums can sometimes work magic and turn back the hands of time. Saving these moments of timeless grace—even the blood-covered grace of The Gross Clinic—fromthe whims of the past brings us closer to the living artists even more. Perhaps Eakins’ will show up for his birthday party after all. But don’t expect him to blow out all 166 candles.

[Image: Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), 1875. (Post-conservation, 2010). Thomas Eakins, American, 1844 -1916. Oil on canvas, 8 feet x 6 feet 6 inches (243.8 x 198.1 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of the Alumni Association to Jefferson Medical College in 1878 and purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007 with the generous support of more than 3,500 donors, 2007.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the image above and inviting me to the press preview for An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing The Gross Clinic Anew, which runs through January 9, 2011.]