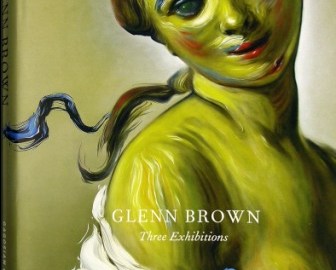

Variety Show: The Art of Glenn Brown

“I tend to think of the exhibitions I do as a loose accumulation of paintings with no single theme—like a variety show,” artist Glenn Brown said in 2007. “A comedy act, a magician, dancing girls, a ventriloquist, and of course a good impressionist make, I think, a reasonable show.” Glenn Brown: Three Exhibitions, a survey of shows from 2004, 2007, and 2009 published by Rizzoli and the Gagosian Gallery, gives you a front row seat at the variety show that is Brown’s art. The cast of characters comes from the collected imagery of art history’s past. But rather than a mere revival show, Brown’s revue is something new. “Brown has likened himself to Dr. Frankenstein,” Rochelle Steiner writes in her essay, “creatively piecing together sections of figures, backgrounds, colour palettes, shadows, and compositions, among other elements—but his approach goes far beyond that of cutting and pasting to create works of art that are without doubt his own.” It’s alive, you’ll scream, as you see the good doctor slice and dice past masters into a modern mastery of his own.

Steiner focuses on this mash-up method of Brown’s. For example, Brown’s Nausea (2008) and The Great Queen Spider (2009) both reference Diego Velazquez’s Portrait of Innocent X “but also lurking is the spirit of Francis Bacon and his Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X,” Steiner observes. “In Brown’s hands,” Steiner continues, “the reproduction of the seventeenth-century image is irreverently turned on its head and distorted, as if the blood has been drained from the pope’s body as part of his conversion into an ethereal winged creature.” Even if you view the inversion as imitative of Georg Baselitz, Steiner praises Brown’s “cropping [of] the head and feet, [through which] he transforms the semitransparent entities into strange mothlike apparitions of undefined size, with a vertebrate structure at the bottom and decorative ‘eyes’ at the top.” Even the twisted mind of Bacon never saw a killer moth in the painting of the malevolent pontiff. Brown goes there, again and again.

For art history buffs, Brown is a veritable buffet. A painting such as 2009’s Star Dust combines Jean-Honore Fragonard and Jeff Koons. A short list of influences (and this is the short list) includes in no chronological or rational order Chaim Soutine, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Gustave Courbet, Arnold Bocklin, Frank Auerbach, Vincent Van Gogh, Willem de Kooning, Salvador Dali, Anthony van Dyck, Rembrandt, Matthias Grunewald, and Arcimboldo. Yet what flows from all those who came before and exudes from Brown’s work as uniquely his own is the sense of life within the paintings. “[W]hat appear as colourful patterns and surface textures emerge as embedded eyes, orifices, and suggestive features that point to alternate realities embedded within and underlying his subjects,” Steiner writes. “A portrait, a figure, a head, or a foot might also be a ghost, a zombie, a planet, a faraway point.” For David Freedberg, whose essay dates from a 2004 show, Brown seems a magician of painting. At first, Brown seems “one of the great exponents of the vigorous stroke, of brilliant impasto, of the thick and decisive line,” yet when standing before the paintings in reality, you see that he paints “with all the care and precision of an old master, everything is perfectly smooth,” Freedberg explains. Just when you think you understand what Brown is doing, you don’t. He eludes our grasp just as his swirling, pulsating figures would slip between our fingers if they existed in our world.

Michael Bracewell, in an essay from 2007, captures the essence of Brown perfectly. “Brown’s paintings are above all performances,” Bracewell realizes, “séance as vaudeville; the clanking of chains as ‘easy listening.’” The substance of the Brownian performance for Bracewell is “accumulated thought at pictorial mulch, as though the pulses and currents of the mind could be seen as corporeal matter.” Francis Bacon once called his mind a “pulverizing machine” for images, and Brown’s mind works much the same way, composting even Bacon along with the rest to produce fertile material for his imagination to sow. Here is a strange and sometimes bitter crop, but one that always leaves you revving up the “pulverizing machine” of your own mind.

Freedberg sees Brown “set[ting] painting free on a new road. It is avowedly not the high road, but there is much to explore along the way.” I beg to differ, unless that “high road” is the road of elitists. Brown allows us all to enter the fray of the performance of painting by upsetting all expectations and churning the whole convoluted mess into something interesting, if not coherent. We walk away from his variety show bewildered, perhaps, but always entertained and wanting more. Glenn Brown: Three Exhibitions, with its combination of fascinating text (Bracewell’s line about “Palest pink and liquid violet abut satanic vermilion—an alarming confection” will whet your appetite) and generously colorful and large-scale reproductions, is your ticket to a sneak peak at what might be the future, via the past, of art.

[Many thanks to Rizzoli and for providing me with a review copy of Glenn Brown: Three Exhibitions and to Gagosian Gallery for providing me with the cover image above.]