Reality Show: Warhol’s Motion Pictures at the MoMA

Long before “The Situation” and his kind entered the zeitgeist, Andy Warhol filmed his own reality show featuring his personal constellation of “Superstars”—artists, musicians, poets, actors, models, and sometimes just people hungry to be in the spotlight who ranged from being Warhol’s friends to mere acquaintances. In Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, currently at the MoMA through March 21, 2011, these wannabes and never weres finally hit the big time in an exhibition that seems almost mundanely modern if it weren’t more than 40 years old. In looking at Warhol’s prescient reality programming, we see the roots of our current obsession with watching other people simply being themselves and with wanting to be watched ourselves.

In late 1962, Warhol found himself obsessing over celebrities in now-iconic silkscreen paintings of figures such as Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley. The recently departed blond bombshell seemed a more obvious choice for veneration than “The Pelvis” at the time, but Warhol recognized early the tragic trajectory of the multimedia star from Tupelo, Mississippi. By repeating the beautiful face of Monroe repeatedly, Warhol diluted its power to entrance and replaced it with a different type of fascination—celebrity born of just being famous rather than of being famous for actually doing something. Spectacle had become the new normal in extreme cases such as that of Marilyn and Elvis. Warhol soon decided to turn the equation around and see if he could take normal and turn it into spectacle.

Using a 16-mm black-and-white Bolex camera incapable of recording sound, Warhol created films with unexciting titles such as Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), and Kiss (1963–64). Sleep consists of over 5 hours of watching poet/performance artist John Giorno snoozing away. In Eat, Robert Indiana munches on a mushroom for 45 minutes. Different couples appear kissing in slow motion in Kiss. In each of these films very little happens, and nothing that we haven’t seen before. Warhol takes reality to the extreme of its lack of uniqueness, except that it’s all caught on film. Warhol’s crowning achievement of nothingness on film may be Empire, eight hours concentrating on the Empire State Building. Empire is the Shoah of Big Apple architecture—a mind-numbing meditation on an immense subject that few can sit through to the end. All of these films appear (in the case of Empire, as special screenings) in the exhibition.

The real reality stars of the exhibition, however, are Warhol’s “Superstars” captured in nearly 500 short films between 1964 and 1966 now known as “Screen Tests” as a nod to the old movie studio practice of shooting actors and actresses in character as a dry run before full-throttle filming began. Warhol shot these “Screen Tests” on a 24 frames per second film but demanded that they be projected at the slower 16 frames per second of the old silent film era. This speed reduction results in a kind of slow-motion awkwardness that makes the figures seem even more vulnerable before the camera. In the early “Screen Tests,” Warhol asked the subjects to remain as still as possible and do nothing. Edie Sedgwick, perhaps Warhol’s greatest star, stares into the lens with a blank beauty in her “Screen Test.” An heiress looking for fame, Sedgwick failed miserably as an actress, fell hopelessly into substance abuse, and died at the age of 28. Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian, and other celebrity heiresses can look to Edie as a kind of godmother, and a cautionary tale. Staring back into Sedgwick’s enormous eyes on a screen mounted on the exhibition wall may be more disconcerting than gazing upon the Warhol’s posthumous faces of Marilyn Monroe. If you visit the MoMA’s exhibition site, you’ll see a selection of new “Screen Tests” created by visitors to the site. The submitters clearly mimic the classic Sedgwick style (as instructed by the guidelines), but you can see that it’s not that much of a stretch for many, a clear sign of our times.

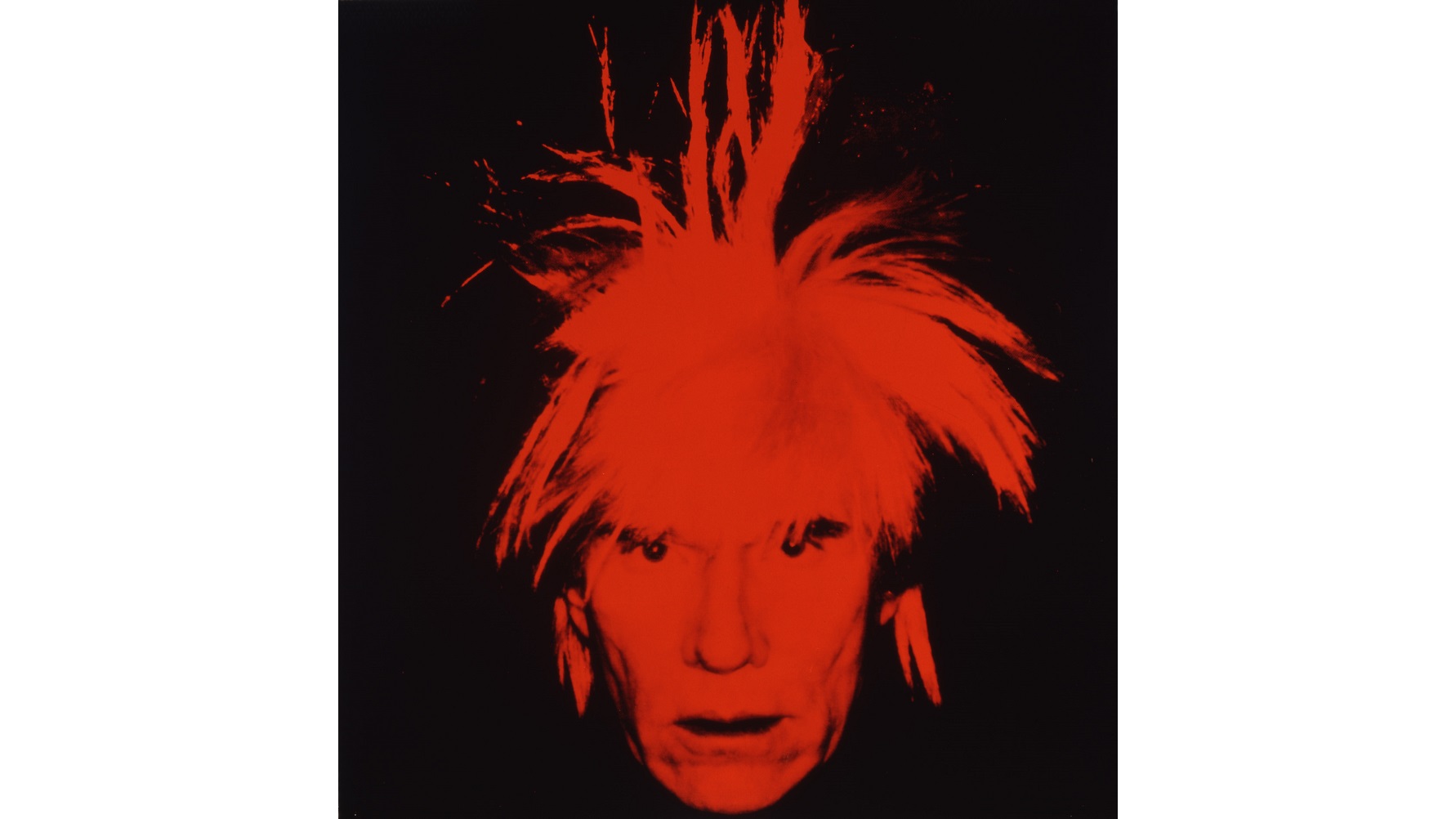

In later “Screen Tests,” Warhol allowed his subjects to move a little and even play to the camera. Unlike Sedgwick, Baby Jane Holzer married into money, but still wanted the Warhol-flavored fame that even money couldn’t buy. In Holzer’s “Screen Test” (a still from which appears above), Baby Jane sensuously brushes her teeth in a form of oral sex as obvious as that focused upon in Warhol’s film Blowjob. The sheer, naked neediness of Holzer to be famous in taking something as, uh, clean as brushing your teeth and turning it into something not suitable for children seems less shocking today in our post-Jersey Shore world, but looking back at this footage should make us reevaluate where we’ve gone.

Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures actually began at the MoMA in 2003 as Andy Warhol: Screen Tests. A year later, the new title caught on as Warhol’s silent films were added to the exhibition as it moved to Berlin. From there, the show has landed in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Buenos Aires, Miami, Moscow, and Prague—making it a kind of Flying Dutchman of the art world, roaming the globe in search of those who will understand. Just as some see the Dutchman as a portent of doom, Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures might be seen as a cautionary tale for a world that’s grown too fond of gazing at its own navel, or the navels of the notorious. Warhol’s prediction of a future in which everyone finds their 15 minutes of fame seems less absurd with each year. In Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures we can look at the past to see a disturbingly clear picture of our present, and future.

[Image: Andy Warhol. Screen Test: Baby Jane Holzer (1964). 16mm film (black and white, silent). 4 min. at 16fps. © 2010 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved. Film still courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum.]

[Many thanks to the MoMA for providing me with the image above and press materials for Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, which runs through March 21, 2011.]