Why Government Agencies Are So Infamously Lame and Why Some of Them are Getting Better

What’s the Big Idea?

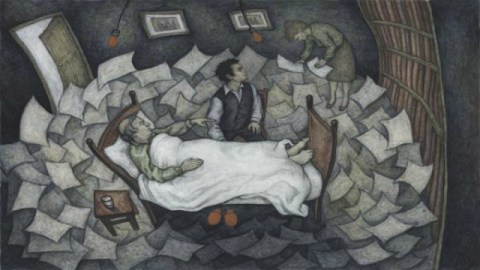

In Kafka’s appropriately unfinished novel The Castle, the protagonist – K. – spends the whole book trying to gain access to the castle that governs a village to which he’s been summoned by a bureaucratic error. He never gets beyond a petty official called “the Council Chairman.” The book is a black comedy of obfuscation, its painful realities so familiar to us that we’ve turned Kafka’s name into an adjective to describe the feeling we’ve all experienced – at the DMV, the passport agency, the Social Security office – that we’re powerless in the hands of omnipotent yet completely dysfunctional government processes.

Why haven’t government agencies changed much since 1922, when Kafka started writing The Castle? According to Tino Cuéllar, who has served in both the Obama and Clinton administration and is the Co-Director of Stanford’s center for International Cooperation and Security, it’s because they’ve got a lot on their plate. People, he says, often erroneously compare government agencies to private corporations and, not surprisingly, find them wanting in efficiency and productivity.

The big difference is that private companies have the luxury of focusing on a few, specific factors – product quality, customer service, and the like. Government agencies like the FDA, on the other hand, have to factor in the daily concerns of thousands of stakeholders, and plan for contingencies that could affect millions.

Mariano-Florentino “Tino” Cuéllar on hopeful signs of improvement in the FDA and Homeland Security

Even in a perfectly designed government agency, if such a thing could exist, the review processes necessary to avoid disastrous errors would be elaborate and time-consuming. That said, Cuéllar argues that agencies can – and some do – improve significantly by focusing on and refining their approaches to professional competence, promotion, internal culture, and effective channels for public input.

Cuéllar cites as an example the FDA’s new regulatory science initiative. Faced with cutbacks and pressure for quicker drug approval processes, the FDA is developing more efficient approval processes that don’t compromise on safety standards. The Department of Homeland Security is learning, too, he says – the public backlash against post 9-11 wiretapping and other infringements of civil liberties has led the agency to develop a “civil rights and civil liberties impact assessment” – a measure based on the idea of environmental impact assessment and designed to help DHS minimize the negative impact of its programs on citizens.

What’s the Significance?

Cross-pollination of successful ideas – between government agencies and between the public and private sector – is responsible for many of the improvements Cuéllar has observed. He argues that although the challenges they face are enormous, agencies can improve by focusing intensely on the factors they can control, and borrowing the best ideas from elsewhere. A policy of openness to outside influences – to smart ideas, wherever they occur – can act as an antidote to the kind of claustrophobic, insulated, self-referential government culture whose inability and unwillingness to learn from its own mistakes Kafka skewered so accurately almost a century ago.

Follow Jason Gots (@jgots) on Twitter

Image credit: Anastacia Kaschte