The Neuroscience of Creativity and Insight

What’s the Big Idea?

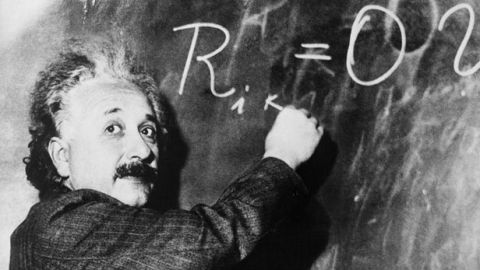

The Internet has a terrible habit of misquoting Einstein on energy and creativity until he sounds like he’s the author of The Secret, not the theory of relativity. Here’s something he actually did say. Describing the effect of music on his inner life, he told a friend: “When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come close to the conclusion that the gift of imagination has meant more to me than any talent for absorbing absolute knowledge.” At times, he explained, “I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.”

Today, what Einstein believed intuitively – that insight was essential to scientific discovery and to the arts – can be observed methodically in the lab. Thanks to the invention of fMRI imaging, neuroscientists are capable of peering into a living, thinking brain in a way that their predecessors never dreamed of, with the potential to test long-standing ideas about how we arrive at novel solutions.

Eric Kandel is a pioneer in the field who worked alongside Harry Grundfest in the very first NYC-based laboratory devoted to the study of the brain. In 2000, he was awarded a Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine for showing that memory is encoded in the neural circuits of the brain. Kandel believes that we’re on the verge of reaching an understanding of the nature of creativity that is more than anecdotal.

Watch our live interview with Eric Kandel, which originally aired 3/22/2012:

“There are a group of people who have studied aspects of creativity,” he says. “And they found that when people do it in a sort of creative way, the ah-ha phenomenon, there is a particular area in the right side of the brain that lights up. And they show this not only with imaging, but also with electrophysiological recording.”

The ah-ha phenomenon or Eureka effect is the well-documented flash of insight that occurs when, after much thought, a solution seems to suddenly just come to you. A recent paper by G. Jones of the Centre for Psychological Research in Health and Cognition, describes the two major theories of cognitive insight:

Insight in problem solving occurs when the problem solver fails to see how to solve a problem and then–“aha!”–there is a sudden realization how to solve it… The representational change theory (e.g., G. Knoblich, S. Ohlsson, & G. E. Rainey, 2001) proposes that insight occurs through relaxing self-imposed constraints on a problem and by decomposing chunked items in the problem. The progress monitoring theory (e.g., J. N. MacGregor, T. C. Ormerod, & E. P. Chronicle, 2001) proposes that insight is only sought once it becomes apparent that the distance to the goal is unachievable in the moves remaining.

What’s the Significance?

In the genre of study Kandel is referring to, researchers use fMRI to measure neural activity in participants solving a visuospatial creativity problem involving divergent thinking. The result? Creativity is not something that can be pinpointed to one specific region of the brain, but creative tasks do seem to engage the right side of the brain in particular.

The study of right-brain creativity stems all the way back to the work of John Hughlings Jackson, a nineteenth century physician whose work at the National Hospital for the Paralyzed and Epileptic in London laid the groundwork for the modern practice of bedside neurology.

Influenced by Darwin’s theories, Hughlings Jackson believed that the self was a function of the brain which had evolved along with the human species. (He was, by at least by his own estimation, the first person to use the word “self” in medical literature.) He discounted the idea “that there exists a centre of the nervous system that acts as a metaphysical interpreter, standing outside of sensory and motor function,” and aimed instead to locate the mind in the physical body, and to understand its mechanics.

Based on his clinical observations, Hughlings Jackson theorized that the left hemisphere is especially involved in language, logical processes, calculation, mathematics, and rational thinking, while the right hemisphere is involved in musicality and synthesis, an aspect of creativity.

Evidently, Hughlings Jackson was right, says Kandel. (Both men fall squarely on the side of reductionism, an epistemological worldview which claims that methods and properties in one domain of science can be explained by another). “The sing-song in my language comes from the right hemisphere, the grammar and the articulation comes from my left hemisphere.”

Hughlings Jackson also believed that in typical brains, the two hemispheres inhibit one another, but brain damage occasionally changes that relationship. “So,” Kandel explains, “if you have lesions of the left hemisphere that remove the inhibitory constraint on the right hemisphere, [it] frees up certain processes.” Surprisingly, Hughlings Jackson found that children that developed an aphasia or language difficulty late in life sometimes also developed a musicality that they didn’t have before.

More recently, researchers analyzing frontotemporal dementia have found that when the dementia is expressed solely on the left side, patients being to show creativity that they’ve never had before. People who develop this type of dementia, which is related to Alzheimer’s, have been known to take up painting for the first time in their lives, or to start experimenting with the use of new colors and forms, if they have been painters.

“This is quite unusual,” says Kandel. “It’s conceivable that as we get deeper and deeper insights into the mind, artists will get ideas about how combinations of stimuli effect, for example, emotional states that will allow them to depict those emotional states better.”

He elaborates, “It’s amazing we know anything about creativity, but this is certainly – we are heading into an era in which one can really get very, very good insights into… the kinds of situations that lead to increased creativity, you know, is group think productive? Does it lead to great – greater creativity or does it inhibit individual creativity? Lots of these questions are being explored, both from a social psychological and from a biological point of view.”