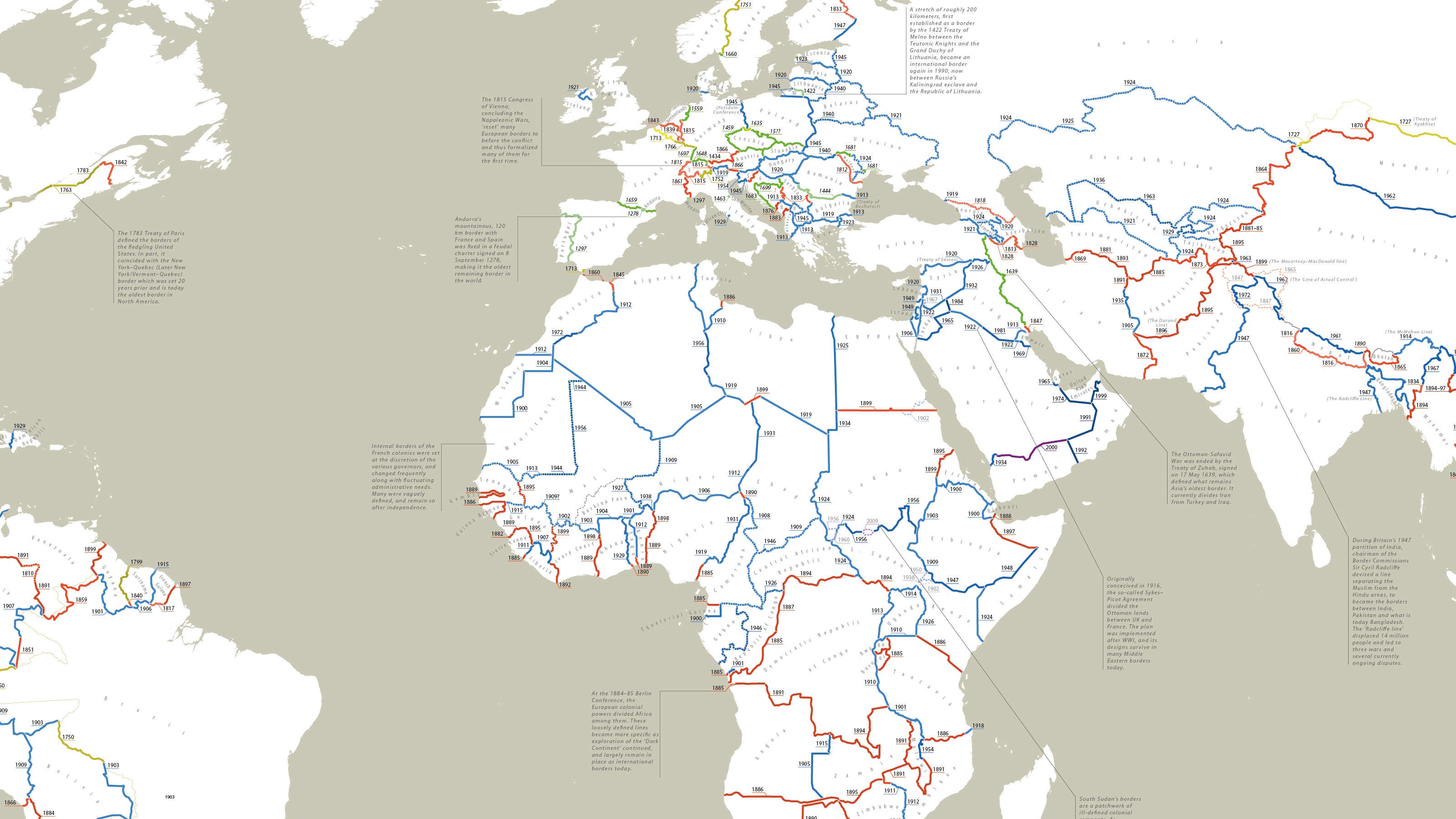

585 – Poitiers All Over Again: Pastry, Islam and Isoglosses

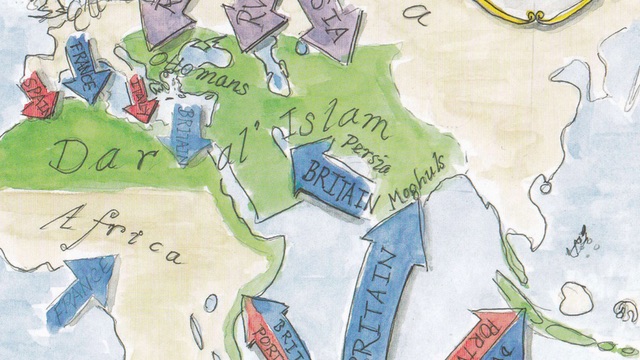

Among the baker’s dozen of legends obscuring the true origin of the croissant, the one repeated most often transports us back to Austria in 1683. Up before dawn, Vienna’s bakers notice the besieging Ottomans [1] preparing a sneak attack. They raise the alarm, and save the city. Their contribution to the Ottomans’ ultimate defeat is immortalised in a crescent-shaped pastry, reminiscent of the half-moon on the Ottoman flag [2].

So is the humble croissant an old symbol of the clash between Islam and Christianity? Perhaps. But you could also argue the reverse. Another origin story [3] tells of the croissant’s invention to celebrate the world’s first major alliance between a Christian and a Muslim power. The alliance was concluded in 1536 by King François I of France (nicknamed au Grand Nez, or ‘Big Nose’) and Suleiman the Magnificent. It held, in some shape and form, until Napoleon’s invasion of Ottoman Egypt in 1798.

The answer may remain elusive, as crescent-shaped pastries have been attested in Austria and France centuries before the first siege of Vienna, or the Franco-Ottoman alliance.

As ancient and mysterious as its origins are, the croissant’s popularity is puzzlingly recent. The earliest known recipe for the modern croissant dates from the first half of the 20th century, when it became a permanent fixture of French cuisine. Its traceable culinary history is only a century older. In the late 1830s, the Austrians August Zang and Ernest Schwarzer opened a Boulangerie viennoise in Paris, selling the sweet bread and puff-pastry products that became known and popular as viennoiseries [4]: croissants, pains aux raisins, brioches, etc. These are typically eaten at breakfast, or as on-the-go snacks.

Now it seems that another member of the viennoiserie family has been drawn into the clash of civilisations. On the 5th of October, a French politician caused a stir when he decried an incident in one of the suburbs where many of the country’s Muslims work:

“I can understand the frustration of some of our compatriots in some quarters [i.e. city areas], where fathers and mothers return home from work to hear that their son had his pain au chocolat taken from him when leaving school by thugs who told him that he couldn’t eat during [the daytime in] ramadan”.

The comment was made by Jean-François Copé at a meeting of the right-wing UMP party at Draguignan. Copé is the opposition party’s parliamentary leader, and candidate for its overall presidency. The latter fact may explain some of his more ‘muscular’ speeches, such as an earlier one attacking so-called ‘anti-white racism’ in France, and the title of his book: Manifeste pour une droite décomplexée [5].

To be a successful politician, this simple mantra will suffice: Find out in which direction the people are marching, and then go march in front of them. Copé would not be the first European politician in recent years to rise to prominence on the back of nativist frustrations with the continent’s rapidly changing demographics.

That his critics denounced his pain au chocolat remark as toxic demagoguery, and a cynical overture to the electorate of the far-right Front National party (which polled 25% in Draguignan during the recent presidential elections), will probably not have bothered Copé – who made sure his remark was reposted on YouTube and Twitter. Even for certain seemngly impalatable political views, there is no such thing as bad publicité [6].

But then a strange thing happened. Copé’s remark did lead to a nationwide debate – with a twist. To the undoubted frustration of those wishing to stir up animosity between religious groups, the debate turned to matters of language. The subject was not Islam versus laïcité [7],but pain au chocolat against chocolatine. For Copé referred to the delicacy – puff pastry around one or two chocolate bars – by its northern name. In the south of France, it’s not pain au chocolat, but chocolatine. But where exactly?

Two web developers in the south-western French town of Poitiers were particularly offended by the pain au chocolat discussion. Surely, the right name for it is chocolatine!

Using a method reminiscent of the French Kissing Map (discussed earlier as #210) Romain Menard and Adrien Van Hamme decided to put the question directly to France’s internet users (or internautes), and then tally up the results, département by département. The result is a homemade, but statistically relevant isogloss map [8] showing the distribution of both variants throughout France.

“Turns out our town Poitiers is on the border, both geographically and lexically, between pain au chocolat and chocolatine“, says Van Hamme.

And the winner is… quite clearly, the pain au chocolat. On 16 October, with just over 18,500 votes counted, the northern variety had garnered 62% of the votes, putting the south-western variety in a sizeable minority, with 38% (however, at the time of writing, the tally is just over 32,000 votes, and pain au chocolat‘s lead has shrunk to 59% versus 41%. This may be due, the accidental pollsters admit, “to over-mobilisation by one side of the argument. In the case of chocolatine, there’s a connection between the term and a regional identity which is missing with pain au chocolat”.

The map quite clearly supports that thesis: even though chocolatine is not unheard of in the rest of France – 7% in the département du Nord prefer the term, as do 11% in central Paris – it is dominant only in the south-west: 97% in Pyrénées-Atlantiques, 73% in Cantal. The department of Pyrénées-Orientales, around Perpignan, is a deep-south exclave of the northern variant (77% vs. 23%).

To spur on the discussion even more, the Poitiers pollsters also include a graph, lifted from Google Books, showing the occurrence of both terms in (French) literature throughout the 20th century. The graph quite clearly shows that chocolatine was the dominant variant, reigning unopposed until the late 1930s, and then swiftly and brutally eclipsed by pain au chocolat.

So chocolatine is not so much a regional variant, as a former ubiquitous term that has found refuge in a region that is safely remote from the national capital. This only intensifies the mystery: what’s so special about the south-west of France?

Well, for one, the region often votes quite distinctly in French national elections [9]. Also, the area vaguely corresponds to the Visigothic kingdom defeated and conquered at Vouillé in 507 by the Merovingians [10].

But – and here we come back to the civilisational clash that Mr Copé so adroitly evoked with his pastry anecdote – the location of Poitiers on the border of the two word variants echoes another time when the city resonated with the clash of two different world views. At Poitiers in 732, a Frankish army under Charles Martel halted the Umayyad march into Europe. As a result of that battle, Muslim influence was limited to the Iberian peninsula, and the foundations were laid for the French state.

Having said that, could the residual influence of the Muslim invaders in the south-west not be responsible for the local preference for chocolatines over pains au chocolat? Perhaps those thugs mentioned in Mr Copé’s anecdote didn’t so much mind the pastry, as the name the victim used to refer to it. Maybe it’s time for a crusade against chocolatines and other words beloved by foreigners and south-westerners. Who knows, this might yet turn into a vote-winner for Mr Copé.

________________

[1] This is the Second Siege of Vienna by the Ottomans. The first one was laid in 1529 by Suleiman the Magnificent, 10th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Although both failed, they had different outcomes for the defeated besieger, not unconnected to their status. Suleiman simply turned his attention to other theatres of war, in the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and elsewhere. The second defeat was incurred not by a Sultan, but by a subordinate Grand Vizier, Kara Mustafa Pasha. He was strangled with a silk cord in Belgrade, his head delivered in a velvet bag to Mehmet IV, the 19th Sultan.

[2] The crescent as a vexillological symbol predates Islam, and was known to the pagan Byzantines, who associated it with the cult of Artemis/Hecate, goddess of the moon. It has been suggested that the Ottomans appropriated the Byzantine crescent and star (perhaps added as a Christian reference, to the Virgin Mary) after their conquest of Constantinople in 1453. However, the crescent had had symbolic significance to the Turks since pagan times too. By centuries-long association with the Ottomans, the crescent now has immediate Islamic associations. Star and crescent remain present on the Turkish flag, and on the flags of many other Islamic countries, from Mauritania to Malaysia, and institutions, such as the Red Crescent, sister organisation to the Red Cross.

[3] Yet another one has the croissant migrate from Vienna to Paris in 1770, as a favourite snack of Marie-Antoinette, the Austrian princess who became France’s last pre-Revolutionary queen (yes, she of “Let them eat cake” infamy. Perhaps because she wanted to have all the croissants for herself).

[4] ‘Stuff from Vienna’. Compare chinoiserie, as in Chinese-style porcelain objects and other artwork with an oriental flourish.

[5] ‘Manifesto For An Uninhibited Right’, with ‘right’ as in ‘political right-wing’.

[6] One criticism of Copé’s remark may prove more crucial than others: this year’s ramadan occurred in August, when schools were closed. So the incident he referred to is at least not recent, and perhaps not real.

[7] This typically French version of secularism denotes a separation of church and state that is so strict that the state is even prohibited from recognising religions per se. Consequently, some critics consider the French state not neutral, but hostile to religion.

[8] An isogloss map shows the geographical boundaries between linguistic features, be they syntactic, semantic or related to pronunciation. Earlier examples discussed on Strange Maps include #500 and #308.

[9] See #108 for a discussion on the 2007 presidential elections, in the first round of which the southwest voted for Ségolène Royal (and Francois Bayrou) rather than Nicolas Sarkozy.

[10] See Norman Davies’ fantastic ‘Vanished Kingdoms‘ for a brief history of Visigothic Tolosa, and a handful of other European states that vanished not just from history, but also from the history books.