Ask Ethan: Why do galaxies still collide in the expanding Universe?

- On the largest of cosmic scales, the Universe is expanding: with individual objects, like galaxies, being driven apart from one another due to the expansion of the space between them.

- Even with dark energy, though, which drives objects in the Universe apart at ever-increasing speeds, galaxies continue to collide and merge, even this late in cosmic history.

- Why is this the case? How do galaxies continue to merge and collide, even as the expanding Universe drives everything apart? It all depends on if you grow massive enough fast enough.

Here in our Universe, an astrophysical phenomenon continues to occur that seems paradoxical. The Universe is expanding, and the expansion itself is accelerating due to dark energy, causing distant objects to recede from one another at ever-increasing rates. When we look at galaxies, we see this directly: the farther away they are from us, the faster they recede from our perspective. Moreover, because of dark energy, if we watch any individual galaxy recede from us over time, we’ll find that it speeds up in its recession: exactly what we mean when we say that the Universe’s expansion is accelerating.

And yet, all across the Universe, both nearby and far away, galaxies — the very objects that should all be receding mutually away from one another — are seen interacting: merging, colliding, and cannibalizing one another. How are these two seemingly contradictory things both consistently true? How can the Universe be expanding, with galaxies receding away from one another, while galaxies are also finding each other, colliding and merging, simultaneously? That’s what Tom Peacock wants to know, writing in to ask:

“If the universe is expanding like a balloon, or a baking muffin with raisins in it (raisins being galaxies), then how is it possible for galaxies to collide?”

It’s a very deep question, and to answer it, we have to understand how gravity works within the expanding Universe. Let’s dive in!

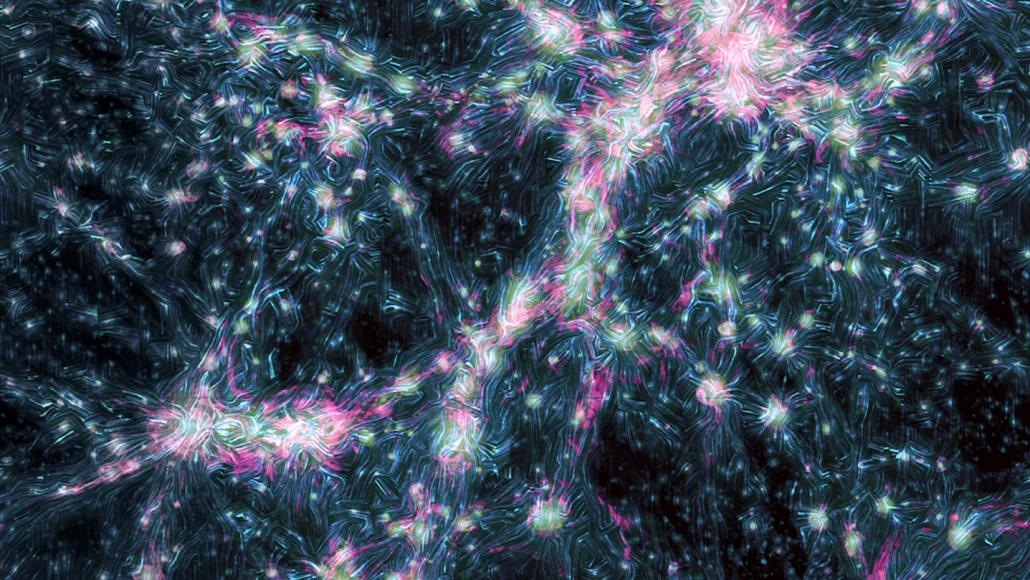

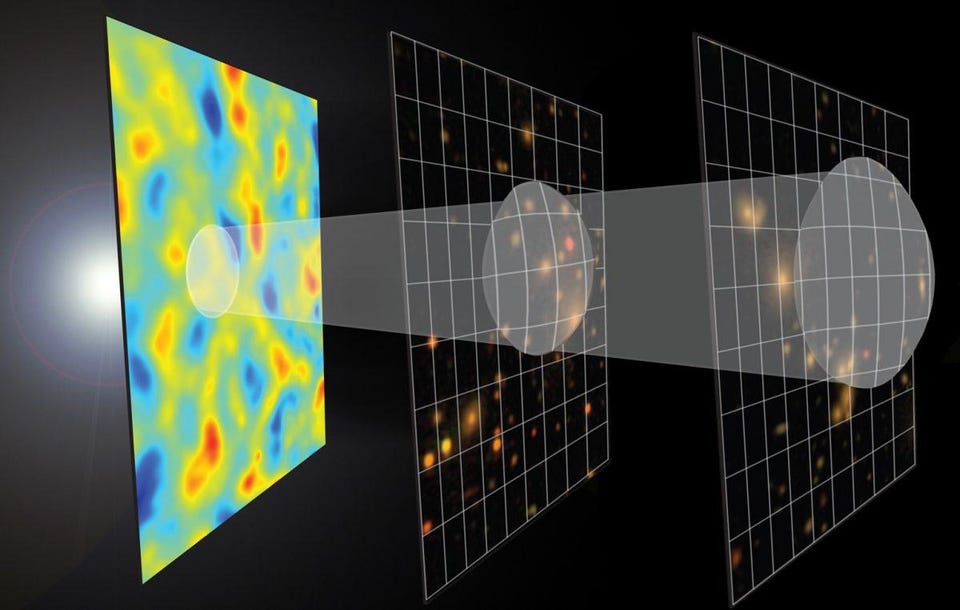

Take a look at the image above.

Do you recognize what it might be?

Believe it or not, it’s the result of a large-scale simulation that models how the Universe evolved over the past 13.8 billion years of cosmic history. Beginning with a set of initial, seed density fluctuations at only the 1-part-in-30,000 level, atop an otherwise uniform background, this is the cosmic web that results. There are filaments that extend for more than a billion light-years in length, intersecting at various nexuses, where they connect, and with giant bubbles of emptiness, or cosmic voids, permeating the regions between them.

Perhaps the most striking property of this image is the following.

On small cosmic scales, or scales smaller than around 1.4 billion light-years, the Universe is incredibly non-uniform. There are regions with practically nothing in them: completely void-dominated. There are regions with one or more large filaments passing through them: regions rich in galaxies. And there are regions where multiple filaments interconnect: regions where galaxies “fall in” to a galaxy group or cluster, some of which contain thousands of Milky Way size galaxies and quadrillions of Suns worth of matter.

But on large cosmic scales, particularly if you look at scales that aren’t just a few billion but tens of billions of light-years in size, the Universe is incredibly uniform: what cosmologists call isotropic and homogeneous. Those two fancy-sounding words just mean that the Universe is the same in all directions (i.e., it doesn’t matter which orientation you look in; the Universe looks the same) and the same in all locations (i.e., it doesn’t matter whether you’re here or anyplace else; the Universe looks the same).

There’s a reason for this: the entire Universe, as well as every part of the Universe, is involved in a great cosmic race. On one hand you have the overall expansion of the Universe, which has been going on ever since our Universe-as-we-know-it began with the hot Big Bang. (And yes, it was expanding even before that, but that’s a story for a different time.) On the other hand, you have the force of gravity, which works to attract all forms of matter-and-energy toward one another.

Who wins the race?

The answer is that it doesn’t just depend on which impetus is stronger: expansion or gravitation. It also depends on how much time has elapsed, because even though our Universe is enormous at present, the speed of gravity is finite and limited; it’s “only” equal to the speed of light.

This is incredibly important for understanding how the Universe evolves. Try to imagine the Universe as it was near the very start of the hot Big Bang, if you dare. The Universe, because it’s expanding and cooling today, must have been much smaller, denser, and hotter in its very earliest stages. (It also was expanding much more rapidly than it is at present, but that’s a little less important for now.) The Universe wasn’t “born” perfectly uniform, but rather arose from an earlier period known as cosmic inflation, which seeded the Universe, on all scales, with density imperfections.

- Some regions are born overdense, with approximately (for a typical overdensity) 0.003% more matter-and-energy in them than the average region.

- Some regions are born with the average density, having only the typical amount of matter-and-energy within them that an average region possesses.

- And some regions are born underdense, with approximately (for a typical underdensity) 0.003% less matter-and-energy in them than an average region of space.

Sure, you’ll very rarely get a large overdensity or underdensity, where they might have as much as 0.01% more-or-less matter-and-energy than average, but overall, everything is still very uniform. A key thing to keep in mind, however, is that these overdense and underdense regions are found on all cosmic scales, from small, microscopic scales to meter-sized scales to light-year-sized scales to scales of thousands, millions, or billions of light years, or even potentially greater distance scales.

Now, the Universe — born with these specific properties — begins to expand, cool, and gravitate. But what is it that happens on each of the cosmic scales?

- On the smallest of scales, gravity can begin influencing the environment around it, because enough time has elapsed for the gravitational signal to propagate over the required distance, even as the Universe expands.

- On larger scales, however, gravity cannot begin influencing that larger-scale environment just yet, as the Universe requires more time for any gravitational signal to traverse those larger distances, taking into account the expansion of the Universe.

What defines the boundary between a scale that’s small enough for gravity to “be felt” and a scale that’s too large for a gravitational signal to reach, given the finite age of the Universe?

It’s the properties of the expanding Universe itself: the expansion rate, the various types of matter-and-energy present within it, and the amount of time that’s passed since the start of the hot Big Bang. All of this together allows us to define what we call a cosmic horizon: or the limitingly large scale over which a gravitational signal (or any signal moving at the speed of light) could have traversed in the amount of cosmic time that’s elapsed.

Early on in cosmic history, for about the first 380,000 years after the hot Big Bang, it’s too hot and dense for neutral atoms to stably form. For every proton or electron in the Universe, there are more than one billion photons left over from the Big Bang, meaning that the Universe has to cool to below a temperature of around 3000 K (about half the temperature of the surface of the Sun) before neutral atoms can form without immediately being blasted apart again. During this time, it isn’t just “gravitation vs. expansion,” but the additional pressure from photons, coupled with interactions between photons and electrons, produce oscillations on small scales: where gravitation gets resisted by radiation pressure.

This leads to a more complex spectrum of density fluctuations: one that peaks (i.e., has the largest density fluctuations) on angular scales of about one degree, which corresponds to length scales of about 800 million light-years (because the Universe expands) today. Then, when the Universe becomes electrically neutral, the following steps occur.

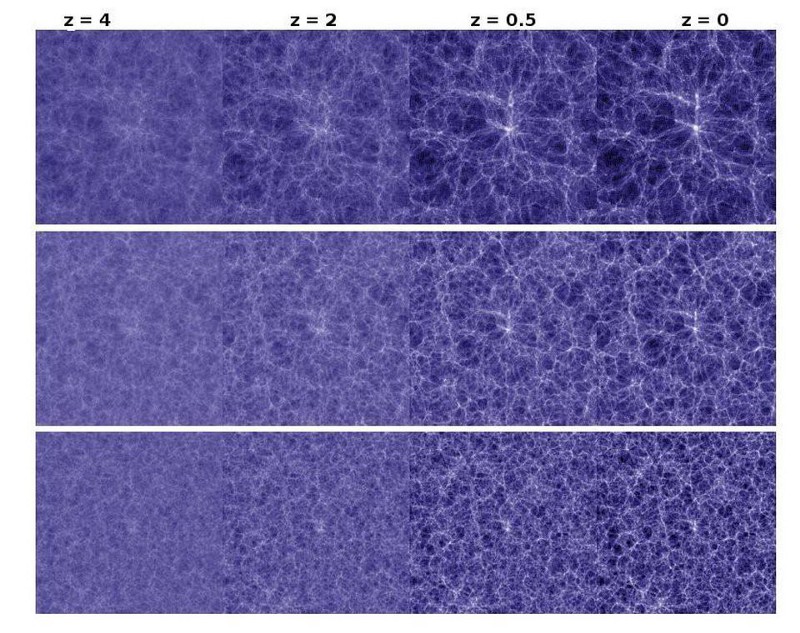

- On scales smaller than the cosmic horizon, gravitational growth occurs, where overdense regions draw matter into them and underdense regions give up their matter to their denser surroundings.

- On scales greater than the cosmic horizon, gravitational growth doesn’t occur until the cosmic horizon overtakes them, meaning that growth doesn’t occur on those larger scales.

- And then, when gravitational growth does begin, it proceeds at a particular rate: growing in magnitude in a way that depends on how large the initial overdensity is.

These initial seed overdensities — the ones that were so small at around 0.003% above average to begin with — will grow and grow until they reach a critical point: about 68% denser than average. This takes a long time:

- tens of millions of years for the scales of star clusters,

- hundreds of millions of years for the scales of large galaxies,

- and billions of years for the largest galaxy clusters.

However, once that critical threshold for an overdensity is reached, gravitational growth and collapse happens rather quickly: in a runaway process that cannot be stopped in the conventional race between gravitation and expansion.

But we have more than just masses that gravitate in a Universe that expands; we also have dark energy in our Universe! Initially unimportant from a cosmic perspective, dark energy has the unique property that even as the Universe expands, its density doesn’t drop. While radiation and matter both get less dense, overall, as the Universe expands, dark energy’s density remains constant, which means that about 6 billion years ago, or 7.8-ish billion years after the Big Bang, the Universe’s expansion began to accelerate. Distant galaxies — or galaxies that aren’t already gravitationally bound together — won’t just speed away from one another, but will speed away at ever-increasing velocities. That’s what it means that the expansion is accelerating: because the speed of distant, receding galaxies continues to rise over time.

So, when we evolve our understanding of the Universe all the way forward, and come to the present time, what does this leave us with?

- On small scales, or scales of an individual galaxy and below, pretty much everything that’s ever going to form has already formed.

- On larger scales, however, like the scale of galaxy groups or galaxy clusters, they’ve all formed in the sense that they’ve become gravitationally bound internally, with all the component galaxies bound together in a large, massive structure. The individual galaxies inside these groups and clusters will still continue merging together, even as the groups and clusters themselves recede from one another.

- On still larger scales, or the scales of cosmic filaments or the space between multiple galaxy clusters, some of them are drifting apart, destined to dissociate. However, some nearby galaxy clusters are gravitationally bound together but haven’t yet merged, and so those galaxy clusters will continue to merge: both at present as well as into the future.

- And on the largest scales of all, or scales greater than or equal to about 1.5 billion light-years, everything that looks like an apparent structure is ephemeral; there are no bound structures on these scales or larger. Claims that there exist larger structures than that are almost certainly untrue.

In other words, dark energy and its effects on the expanding Universe will prevent new bound structures from forming; everything that isn’t already bound together is destined to drift apart, like raisins in a leavening ball of dough.

That’s where the answer lies! The reasons there are still:

- galaxies merging today in the depths of deep space,

- galaxies colliding and merging within groups and clusters,

- and even galaxy groups and clusters colliding,

is because even though the Universe is expanding, and even though the expansion is accelerating, gravitational growth led to these objects becoming gravitationally bound together long ago. Depending on factors like angular momentum, the total mass of the bound structure, and the initial distance of the galaxies (or galaxy groups/clusters) from one another, it can take hundreds of millions, billions, or even tens of billions of years for these mergers to occur and complete.

In fact, we have a series of spectacular examples right here in our own bound structure: the Local Group of galaxies. The Milky Way is the second-largest galaxy in the Local Group, with two relatively massive nearby satellites: the Large Magellanic Cloud and the Small Magellanic Cloud. Yet even though these galaxies are indeed gravitationally bound to our own, it’s going to take several billions of years before they merge and collide with us, as they’re simply not “infalling” but rather moving across the skies relative to us. Andromeda, the biggest galaxy in the Local Group, will indeed merge with the Milky Way as well, but not for another four-to-seven billion years.

You have to remember, when we talk about the expanding Universe being like a ball of dough with raisins in it, that “raisins are galaxies” only applies to isolated galaxies that aren’t bound to a part of any larger structure. Instead, you should think of a “raisin” in that dough as being the largest bound structure that your object-of-interest is a part of.

- For a very isolated galaxy, like MGC+01-02-015, you can treat it as a raisin, as it isn’t bound to anything larger.

- For a galaxy like our Milky Way, you need to treat the entire Local Group that it’s embedded in as a single raisin; our galactic group isn’t expanding at all, as it’s all gravitationally bound together.

- For a galaxy like Messier 87, which sits at the heart of the massive Virgo Cluster, you must treat the entire Virgo Cluster as a raisin, even though it’s nearly a thousand times as massive, overall, as the “raisin” that represents our Local Group.

- And for a galaxy that’s within the colliding set of galaxy clusters known as the Bullet Cluster, you must treat the entire cluster complex, including the multiple clusters inside of it, as a single raisin.

These are all examples of bound structures that behave as raisins within the dough of the expanding Universe. However, with the exception of the “very isolated galaxy,” all of these other examples will still lead to individual galaxies, within the larger bound structure that they’re a part of, colliding and merging together.

Come back in another hundred billion years, though, and you’ll find that all of those mergers have completed. Instead of galaxy groups and galaxy clusters, we’ll just have giant post-merger galaxies, where each one truly does behave like an individual raisin in the dough that is the fabric of the expanding Universe itself.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!