The secret reason the USA beat the USSR to the Moon

- Back in the 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union was far ahead of the USA in the space race, launching the first satellite, the first human into space, and many other spaceflight “firsts.”

- This dominance continued for several years, and by the mid-1960s, they were planning a 1967 Moon landing: years ahead of even the most ambitious schedule for the United States.

- But the unexpected illness and death of one supremely competent but unsung Soviet figure, Sergei Korolev, changed everything. Here’s how it all fell apart, leading to the USA’s ultimate victory.

Not only in the United States, but all across the world, humanity celebrated 2024 as the 55th anniversary of the culmination of the Space Race: the quest to put a human being on the Moon and safely return them to Earth. On July 20, 1969, our species achieved a dream older than civilization itself, as human beings set foot on the surface of another world beyond Earth when they walked on the surface of the Moon, some 380,000 km away. From 1969 through 1972, a total of 12 American astronauts walked on the lunar surface, marking the first and only time to date that human beings have set foot on the solid surface of a world beyond our own planet.

If any nation was going to do it, most thought it was going to be the Soviet Union. The Soviets were first to every milestone in space before that:

- the first satellite,

- the first crewed spaceflight,

- the first person to orbit the Earth,

- the first woman in space,

- the first spacewalk,

- the first landers on another world,

and much more. After the disastrous Apollo 1 fire, it seemed like a foregone conclusion that the Soviets would be the first to walk on the Moon. Yet they never even came close. Why not? The answer lies in a name that most people have probably never heard of: Sergei Korolev. Here’s what everyone ought to know.

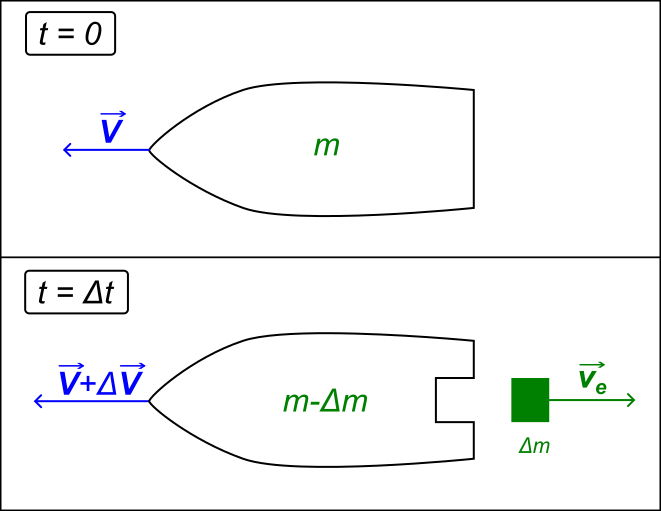

Long before humanity ever broke the gravitational bonds of Earth, there were a few scientists working to pioneer a new scientific field: theoretical astronautics. While it had much in common with conventional aeronautics, based on the physics of Newton, there were additional restrictions and concerns that came along with the idea of journeying into space. Unlike with terrestrial flight, journeying into space necessarily meant:

- needing a fuel source that could propel you in the absence of an atmosphere,

- the ability to continuously accelerate for long periods of time,

- materials that would keep humans and equipment safe at all temperatures and pressures achieved during flight,

- protection against solar and cosmic radiation and the harsh external vacuum of space,

- and calculating how to maximize the deliverable payload with constraints on fuel and rocket mass.

In the early days, all of these concerns were mulled over by theorists alone. A few pioneers stand out in the history of the early 20th century: Robert Goddard, who created and launched the first liquid-fueled rocket; Robert Esnault-Pelterie, who began designing airplanes and airplane engines but later moved on to rocketry, developing the idea of rocket maneuvering; and Hermann Oberth, who built and launched rockets, rocket motors, liquid-fueled rockets, and mentored a young Wernher von Braun.

But before any of them came Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who was the first to understand the vital relationship between consumable rocket fuel, mass, thrust, and acceleration. Perhaps more than any other person, Tsiolkovsky’s early works influenced the development of spaceflight and space exploration across the globe. And while Goddard was American, Esnault-Pelterie was French, and Oberth was German, Tsiolkovsky lived his entire life in and around Moscow: first in Russia, and after the October Revolution, the Soviet Union (or USSR).

Although Tsiolkovsky died in 1935, his work left a lasting scientific legacy, particularly in Russia. Sergey Korolev was Tsiolkovsky’s pioneering experimental counterpart, who dreamed of traveling to Mars and launched, in 1933, the first Soviet liquid-fueled rocket and the first hybrid-fueled rocket. In 1938, however, he became a victim of Stalin’s Great Purge. Korolev was imprisoned in the Gulag, where he languished throughout most of World War II: until 1944.

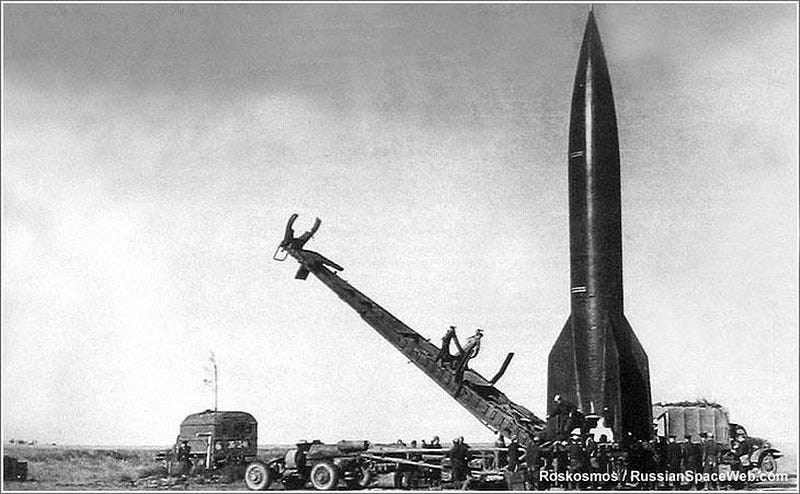

Once World War II ended, both the USA’s and the USSR’s space programs were boosted by the addition of captured German scientists. The USA got most of the top German scientists and a slew of V-2 rockets, but the Soviet Union captured many of the German records, including drawings from V-2 production sites, and also the influential scientist Helmut Gröttrup. Unlike the USA, though, the legacy of Tsiolkovsky gave the Soviets an initial edge.

This combination — of German V-2 technology, Tsiolkovsky’s theoretical work, and Korolev’s brainpower and imagination — proved an incredible recipe for Soviet success in the venture of space exploration. Korolev’s rise upon his release from the Gulag was nothing short of meteoric.

In 1945, he was commissioned as a colonel in the Red Army, where he immediately began work on developing rocket motors. After being decorated with the Badge of Honor later that year, he was brought to Germany to help recover V-2 rocket technology. By 1946, Korolev was put in charge of overseeing a team of many German specialists, including Gröttrup, in the endeavor to develop a national rocket and missile program. Korolev was appointed as chief designer of long-range missiles, where by 1947, his team was launching R-1 rockets: perfect replicas of the German V-2 designs.

Sure, the United States was doing something very similar: launching V-2 rockets from White Sands missile base in New Mexico in the late 1940s, taking full advantage of post-war German technology. But beginning in 1947, the Korolev-led group began working on advancing and improving the design of the Soviet R-1 rockets, leading to greater missile ranges and the implementation of separate-stage payloads, which could easily double as warheads.

By 1949, the Soviets were launching R-2 rockets designed by Korolev, with double the range and improved accuracy over the original V-2 clones, but Korolev was already thinking further. As early as 1947, Korolev had come up with an entirely novel design for an R-3 missile, with a range of 3,000 kilometers: enough to reach England from Moscow.

The incremental improvements to rocket and missile technology accumulated at a staggering pace under Korolev’s guidance. By 1957, the Soviets had achieved the first successful test flight of the R-7 Semyorka: the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile. The R-7 was a two-stage rocket with a maximum range of 7,000 kilometers and a payload of 5.4 tons, enough to carry a Soviet nuclear bomb from St. Petersburg to New York City.

These achievements catapulted Korolev to national prominence within the Soviet Union. He was declared fully rehabilitated, and began advocating for using the R-7 to launch a satellite into space, met with utter disinterest from the Communist Party. But when the United States media began discussing the possibilities of investing millions of dollars to launch a satellite, Korolev seized his chance. In less than a month, Sputnik 1 was designed, constructed, and launched.

On October 4, 1957, the space age officially began. Korolev’s rockets had brought humanity above the bonds of Earth’s gravity and into orbit. While Khrushchev was initially bored with Korolev’s rocket launches, the worldwide recognition for his achievements was too large to ignore on the international stage. Less than a month later, Sputnik 2 — six times the mass of Sputnik 1 — was launched, carrying Laika the dog into orbit.

The launch of the complex Sputnik 3, complete with scientific instruments and a primitive recording device, occurred in May of 1958, demonstrating the capabilities of the Soviet space program. But Korolev had his sights on a bigger target: the Moon. Initially desiring to use the R-7 to carry a package there, Korolev modified the rocket’s upper stage to be optimized for use in outer space and outer space alone: the first rocket designed with such a purpose.

Despite an enormous lack of funding, time pressure, and an inability to test hardware prior to launch, Korolev was determined to launch a payload to the Moon. On January 2, 1959, The Luna 1 mission reached the Moon, but flew past instead of impacting it, which was the intent. (It missed by less than 6,000 kilometers.) On September 14, 1959, Luna 2 succeeded: becoming the first human-made object to arrive on the Moon.

Less than a month later, Luna 3 took the first photograph of the Moon’s far side. In the realm of space exploration, the Soviets were achieving new milestones while the United States was forced to play catch-up. Korolev’s achievements led the way, with his dreams growing ever larger. He sought to make the first soft landing on the Moon, and had his sights on Mars and Venus as well. But his biggest dream was for human spaceflight, and to bring humans anywhere his rockets could take them.

Beginning in 1958, Korolev began undertaking design studies for what would become the Soviet Vostok spacecraft: a fully automated capsule capable of holding a human passenger in a space suit. By May of 1960, an uncrewed prototype was launched, orbiting the Earth 64 times before failing re-entry. On August 19, 1960, two dogs, Beika and Streika, were launched into low-Earth orbit and successfully returned, marking the first time a living creature was launched into space and recovered.

On April 12, 1961, Korolev’s modified R-7 launched Yuri Gagarin into space: the first human to break the gravitational bonds of Earth, and also the first human to orbit Earth. The additional Vostok flights, under Korolev’s watch (he served as the capsule coordinator), included the first inter-spacecraft communications and rendezvous, as well as the first woman cosmonaut: Valentina Tereshkova.

Korolev then began work on the Voskhod programme, with the ultimate goal of sending multiple astronauts into space and eventually to the Moon. As early as 1961, Korolev began designing a superheavy launch rocket: the N-1, which used an NK-15 liquid fuel engine and was of the same scale as the Saturn V. With the capacity for a three-person crew and the capability of performing a soft landing upon return, the Soviets were poised to take the next step in the Space Race.

On October 12, 1964, a crew of three Soviet cosmonauts — Vladimir Komarov, Boris Yegorov and Konstantin Feoktistov — completed 16 orbits in space aboard Voskhod 1. Five months later, Alexei Leonov, aboard Vostok 2, performed humanity’s first spacewalk. The next step was to reach for the Moon, and Korolev was ready. With the 1964 fall of Khrushchev, Korolev was put in sole charge of the crewed space program, with the goal of a lunar landing set to occur in October of 1967, which would mark the 50th anniversary of the October revolution. Everything seemed well within reach.

Korolev began designing the Soyuz spacecraft that would carry crews to the Moon, as well as the Luna vehicles that would land softly on the Moon, plus robotic missions to Mars and Venus. Korolev also sought to fulfill Tsiolkovsky’s dream of putting humans on Mars, with plans for closed-loop life support systems, electrical rocket engines, and orbiting space stations to serve as interplanetary launch sites.

But it was not to be: Korolev entered the hospital on January 5, 1966, for what was thought to be routine intestinal surgery. Nine days later, he was dead from what was reported as colon cancer complications, although many to this day suspect foul play. Without Korolev as the chief designer, everything went downhill quickly for the Soviets. While he was alive, Korolev fended off attempted meddling from a variety of rival rocket designers, including Mikhail Yangel, Vladimir Chhelomei, and Valentin Glushko. But the power vacuum that arose after his demise proved catastrophic.

Vasily Mishin was chosen as Korolev’s successor, and disaster immediately followed. The Soviet goals for their space program remained barely changed at all, with plans to have humans orbit the Moon in 1967 and just a little later to land on the Moon in 1968. Mishin was under tremendous pressure to achieve these goals; failure was unacceptable. On April 23, 1967, the Soyuz 1 mission was launched, with Komarov on board: the first crewed flight since the death of Korolev.

Despite 203 design faults reported by project engineers, the launch still occurred, immediately encountering a series of failures. First, one solar panel failed to unfold, leading to inadequate power. Then the orientation detectors malfunctioned, the automatic stabilization system failed, and the launch of Soyuz 2, expected to rendezvous with Soyuz 1, was cancelled due to thunderstorms. Komarov’s report on the 13th orbit led to a mission abort; 5 orbits (about 7 hours) later, Soyuz 1 fired its retrorockets and re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. Due to another defect, the main parachute never unfolded, and Komarov’s manually deployed reserve chute became tangled.

The first flight under Korolev’s successor had ended in the worst disaster imaginable: the first in-flight fatality of any space program conducted by any space agency on Earth. This would prove not to be a one-off event, either, as further setbacks suddenly became the norm. Gagarin, the first human in space, was tragically killed in a test flight in 1968. Mishin developed a drinking problem, coincident with multiple N-1 rocket failures and explosions that followed the Soviet Space program throughout 1969. The lone bright spots came in January of 1969, where the rendezvous, docking, and crew transfer of cosmonauts between two Soyuz spacecraft were achieved.

But the death of Korolev, and the mishaps under his successors, are the real reason why the Soviets lost their lead in the space race, and never achieved the goal of landing humans on the Moon. Smaller goals, such as the first robotic rover on the Moon, as well as the first uncrewed landings on Mars and Venus, were achieved by the Soviet space program in the 1970s, but the big prize was already taken off the table. If not for Korolev’s unexpected decline in health and subsequent death at a critical time, perhaps history would have turned out differently. In the end, the leadership (or lack thereof) by a single, competent person can ultimately be the difference between success and failure.