One Person’s Bully Is Another Person’s Courageous Crusader

Here’s an idea from David Graeber, writing over at The Baffler:

“We are all taught that bullies are really cowards, so we easily accept that the reverse must naturally be true as well. For most of us, the primordial experience of bullying and being bullied lurks in the background whenever crimes and atrocities are discussed. It shapes our sensibilities and our capacities for empathy in deep and pernicious ways.”

Let’s discuss context. Graeber delves into this bully psyche by way of an analysis of the Battle of Rumaila at the end of the First Gulf War. If you’re unfamiliar, the Battle of Rumaila was a controversial engagement that occurred March 2, 1991 — a few days following the official end of the conflict. Iraqi forces were retreating from Kuwait on a highway, their tails tucked firmly between their legs.

That’s when U.S. forces descended upon them.

Most reports indicate that the Iraqis shot first when a U.S. patrol entered into their path of retreat. Either way, the Americans massacred the retreating Iraqis, decimating the armored convoy and killing over 700 people, including women and children. The incident birthed phrases like “the Battle of the Causeway” and “the Highway of Death.” It’s not one of the gleaming highlights of the war, partly because it technically happened after the war, partly because it was an unnecessary act of senseless destruction.

What does all that have to do with bullying? Graeber explains that the powers-that-be, fearing accusations of war criminality, attempted to spin the incident by painting the retreating Iraqis as a good-for-nothing band of “rapists, murderers, and thugs.” Bullies, really. Graeber iterates instead that it was a force made up mostly of kids drafted for a conflict they wanted no part of. And ultimately, that may have been what turned public opinion against them:

“Maybe it was this very refusal that’s prevented the Iraqi soldiers from garnering more sympathy, not only in elite circles, where you wouldn’t expect much, but also in the court of public opinion. On some level, let’s face it: These men were cowards. They got what they deserved.”

This is where we see Graeber’s thesis up top at work. Throughout military history, the deserter has almost categorically been among the most detested role in war. What is a deserter but a person who realizes they’re being oppressed by a giant social machine and wants out? They’re the bullied, and by demonizing them we side with the bullies.

In America, we also see strange conflations of courage and cowardice in both the media and political discourse. Terrorists and other agents of violence and fear are labeled “cowards” for their acts. Call them what you want, says Graeber, but the men who flew jets into skyscrapers were surely courageous. But cowardice, which is such a wide rhetorical umbrella, is a much more effective barb:

“The idea that one can be courageous in a bad cause seems to somehow fall outside the domain of acceptable public discourse, despite the fact that much of what passes for world history consists of endless accounts of courageous people doing awful things.”

Graeber spends the rest of his piece analyzing human nature and forming a counterargument to the common belief that mankind is predisposed to violence and warfare. He examines the juxtaposition of said belief with the idea that natural inclinations toward sympathy and peace are described in many languages by words such as “humane,” which implies that they are essential human traits:

“The question we should be asking is not why people are sometimes cruel, or even why a few people are usually cruel (all evidence suggests true sadists are an extremely small proportion of the population overall), but how we have come to create institutions that encourage such behavior and that suggest cruel people are in some ways admirable — or at least as deserving of sympathy as those they push around.”

This is all really high-protein food for thought.

Graeber then carries this scope down to the school playground to examine the culture of bullying, which he describes as “a kind of elementary structure of human domination.” There’s some great stuff about how bullies tend to take advantage of the authority the school holds over all students, and why “it doesn’t matter who started it” are “probably six of most insidious words in the English language.”

I recommend reading the article fully (I’ve linked it again below). I think the main takeaway is that, culturally speaking, we’ve grown to love, admire, and protect the bully role. We have promoted toxic cultural tropes such as the danger of pointing out abuse (whether by a bully or representatives of the government), the discouraging of those who step in to protect the weak, and reverence for acts that uphold draconian social codes. Graeber insists that this results in us, as a society, failing to react properly to aggression:

“Our first instinct when we observe unprovoked aggression is either to pretend it isn’t happening or, if that becomes impossible, to equate attacker and victim, placing both under a kind of contagion, which, it is hoped, can be prevented from spreading to everybody else.”

And that’s hard to argue against.

Read more at The Baffler.

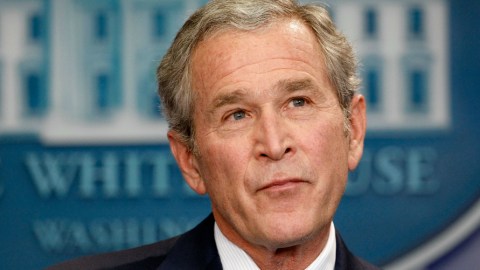

Photo: WASHINGTON – JANUARY 12, 2009: U.S. President George W. Bush holds a news conference in the Brady Press Briefing Room at the White House January 12, 2009 in Washington, DC. Bush spent nearly an hour fielding questions during his last news conference as president of the United States before President-elect Barack Obama is sworn in on January 20. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)