What Happens When An Artist Thinks Like a Scientist? Better Chicken

Sometimes it takes an artist to show scientists what they’ve been missing.

Koen Vanmechelen is that artist. For the last 20 years he’s bred his own chickens as part of the Cosmopolitan Chicken Project (CCP). That might seem strange to you and me, but not to Koen. He mixes DNA the way other artists mix colors, and uses his chickens to demonstrate cultural and genetic diversity. Besides, chickens are one of the most common animals on the planet. There are 65 million of them. They produce 60 million tons of eggs that we use for everything from food to medicine production. That makes chickens “the most important animal in the world,” to Koen, as he told me over Skype. They never fail to surprise him: “Chickens are like a mirror for human culture,” he said. And he’s right.

That’s also why they’re in so many historical paintings. Wall painting at the Boulevard Saint Laurent, Montreal, Quebec Province, Canada, North America. Credit: Guenther Schwermer/GettyImages

Like humans, chickens are descended from a single species. The ancestor of the vast majority of the world’s chickens is the Red Junglefowl, which lives at the foot of the Himalayan mountains. From that one chicken came hundreds of different kinds, each uniquely adapted to their local environments and “reflecting the cultural characteristics of their regions and communities,” as the CCP site puts it. It’s a beautiful example of diversity.

But there’s a dark side to that much localization: genetic inbreeding, which we also see in humans. Over time, gene pools within highly localized, isolated communities become too narrow to sustain, rendering the population infertile. “Diversity is at the root of health,” geneticist Olivier Hanotte explained to me over Skype. “Genetically speaking, we know it’s bad to be inbred.” Particularly when chickens have been bred based on their productivity and efficiency.

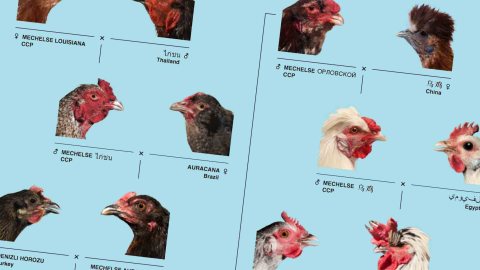

In order to counter that effect and reverse the cycle of genetic erosion, Koen crossbred chickens from different countries to increase their genetic diversity and resilience to disease. He chose a different breed every year to demonstrate that “if we find combinations, then we make evolution,” as he told me.

He’s right about that, too.

The genetic crossbreeds of the Cosmopolitan Chicken Project. Credit: CCP

Each successive generation of chickens was more resilient than its parents. “The chickens lived longer, were less susceptible to disease, and exhibited less aggressive behavior,” the CCP site reports. “Chickens from industry have 4 million bits of genetic code,” Koen told me “My chickens have 40 million. In my 19th generation chickens, the fertility tripled from 30-90%. Their [genetic] diversity increased enormously.” He admitted that the chickens’ “immunity is difficult to prove” but their lifespans have also increased: “now my chickens live for 15 instead of 5 years.”

All of those benefits have been backed up scientifically. “Using SNP genotyping and whole genome sequencing, it has been proven that the CCP shows significantly higher diversity compared to purebred chicken and remarkable increased potential for gene transcription and expression,” the CCP site reports.

Encouraging as that is, that genetic diversity hasn’t been tested in the real world — and that’s where Olivier comes in. Olivier found Koen via a Google search and was immediately intrigued by him and his project. “Koen is thinking as a scientist,” he told me. “He wanted to reconstruct the entire diversity of domestic diversity. Despite his training, he is actually thinking as a scientist. As an artist, he can actually do things that we can only imagine as scientists.” Koen agreed with that. “I think it’s very natural to work together in this way,” he told me about collaborating with a scientist. “For me, that’s art. For the first time in history, we are able to have access to all kinds of different people. If we have to generate new knowledge, we have to make this combination.”

The two are teaming up this year for the Planetary Community Chicken (PCC) project, which will bring Koen’s genetically superior chickens to different communities and test their immunity and biological sustainability in real-world conditions. “The introduction of a new ‘global gene’ to the local flocks breaks the cycle of genetic erosion that can result from local inbreeding and industrial mono-cultural production,” the CCP site explains. “The desired outcome is to breed a stronger chicken that lives longer, and that, as a result, could offer longer-term economic and social stability to farmers.”

Credit: Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

“Compared to other chickens adapted to single local area, it is quite possible his population of chicken can adapt to a very large diversity of environment,” Olivier told me. “Commercial chickens will never survive in the real world. They die rapidly. Koen’s population will be hardy, but not breed so quickly. [Right now, the] crossbreeding that farmers do is breed local with commercial, [but Koen’s chickens] will produce more and continue to survive. That’s the step Koen wants to move to.”

Koen is hoping to test with Olivier at his research site in Ethiopia by the end of the year. He’s also planning to bring the PCC to Zimbabwe, Siberia, Belgium, Cape Town, and Detroit — which is where he’s at right now. He’s displaying his 20th generation crossbreed at Detroit’s Wasserman Projects until the end of the year. He’ll be crossing his 19th generation Mechelse Cemani chicken with the American Wyandotte, a chicken named for a Native American tribe local to the Great Lakes near Michigan. That’ll produce the 20th generation Mechelse Wyandotte — which, since it carries DNA from 20 different breeds, will grant it the biggest DNA pool of any chicken on the planet.

Koen’s excited to see what will happen. “I want people to understand that life only exists because the other senses that you exist,” he told me. “Together we can reach a completely other goal than to just be on your own.” Olivier is excited, too. “There is a mystery in chicken,” he told me. “The more we explore the chicken the more we discover, and the more we discover we know extremely little about it. Koen’s work is helping to understand this mystery. But I think it is just the beginning.”

Check out the mystery for yourself at Detroit’s Wasserman Projects from September 22 to December 17. You’ll never see chickens the same way again.

Credit: Wasserman Projects/YouTube