Did This Medieval African Empire Invent Human Rights?

We usually think of the Magna Carta as the first document to encapsulate any sort of human rights. However, the “Kurukan Fuga Charter” also known as the “Manden Charter” is its contemporary and according to at least one scholar, may even predate it. In 2009, the charter was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. But the charter wasn’t written down. Instead, it was passed down orally from one generation to the next. This went on for centuries, illustrating West Africa’s rich oral tradition.

This may sound like news. Most social studies and history programs teach little about the kingdoms of Africa. Of course we know about ancient Egypt— one of the most influential civilizations in history. But not much is said about the great kingdoms of sub-Saharan Africa such as the kingdom of Kush, the kingdom of Axum, the Land of Punt, the Mali Empire, the Songhai Empire, and the mysterious Zimbabwe kingdom—of which little is known.

At the founding of the Mali Empire, the MandenCharter was born. Sometime in the 1200s, a great warrior named Sundiata Keita pronounced it. Though Disney takes credit for the moniker, Keita was the original “Lion King.” After calling for a rebellion, he raised an army and squashed his sovereign’s forces, consolidating the empire, and eliminating the state of Old Ghana.

At the site of Kurukan Fuga, meaning “clearing on a hard rock,” situated between what is now Guinea and Mali, the resplendent Keita assembled a group of wise men, the chiefs of the various clans. These included Sumanworo Kanté, Emperor of Sosso, whom he had just defeated at the battle of Krina. After the charter’s declaration, it was passed down through griots or bards, the famed storytellers of the region, and keepers of the culture. This is a family affair, and stories and other items are passed down still today from father to son.

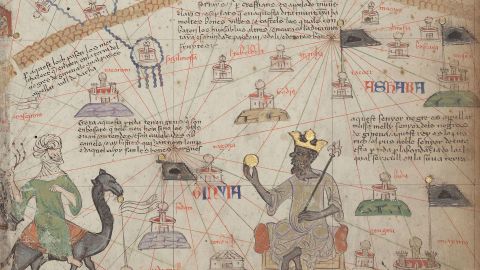

Map of the Mali Empire. Wikipedia Commons.

The spoken document which has also been called a “Constitution” contains a preamble and seven chapters. It speaks on social peace, the sanctity of human life, women’s rights, the right to an education, food security, and even to self-expression. The charter gave equal rights to citizens including women and slaves. The aim was to provide peace and social stability. It advocated diversity and spoke of abolishing slavery, in this case the razzia or raid.

Emperor Keita, having solidified his power, expanded his territory and took part in trade. The West African nation, also known as Mandinka, soon controlled territory from the coastline of Mauretania to the Niger River. In terms of commerce, it took control of the trade routes across the Sahara. Mandinka soon spread its laws, language, and customs throughout West Africa. The empire lasted from 1235 to 1645.

This was a dynastic Muslim kingdom which linked its heritage to the Prophet Mohammad, claiming it had been founded by his muezzin, Bilal. A muezzin is the singer who calls the faithful to prayer. Mali’s cities Djenné and Timbuktu soon grew rich from trade. It wasn’t long before they became renowned for their Islamic schools and extravagant adobe mosques. Timbuktu even had a well-regarded university, containing a library replete with some 700,000 works.

The wealth and opulence of the kingdom is illustrated in a story of one of its most famous kings, Mansa Musa. While making a pilgrimage to Mecca in the 14th century, Musa stopped off in Egypt. It is said that the monarch brought with him thousands in his retinue, perhaps tens of thousands, and a hundred camels loaded with gold. Mansa Musa spent liberally. He distributed so much gold that the value of the precious metal took a nose dive and didn’t recover for a number of years. Some historians even believe he may have been the wealthiest person in all of history.

The Great Mosque of Djenné. By Flickr user: Juan Manuel Garcia, Mexico City.

Over time, the musas or kings lost control of their borders. By the 15th century, another power had risen up, the Songhai Empire, which over time absorbed its predecessor, burying the Manden Charter to all but the griot of the Mande—the empire’s descendants. These are a subset of the Mandingo people, also called the Mandinka or the Malinke. They number 11 million today, living in parts of West Africa, including the Ivory Coast, Guinea, Mali, Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau.

Approximately 388,000 are thought to have been captured and shipped to the Americas during the transatlantic slave trade. This ethnic group was reintroduced to the world in the 1970s when Alex Haley, author of Roots, traced back his heritage to a Mandinka village called Juffure in Gambia. This was where Kunta Kinte, his real-life ancestor, was captured and sold into slavery, eventually landing in the US.

History generally places the Manden Charter at 1236. This predates the English Bill of Rights (1689) and France’s Declaration of the Right of Man and of the Citizen (1789). Most scholars today don’t believe that it predates the Magna Carta (1215-1297). But some do, including French anthropologist and ethnographer Jean-Loup Amselle, who has studied and written about African society, culture, and art, particularly how outside influences are adopted by cultures. He contends that the Manden Charter actually predates the Magna Carta.

Since it derives from an oral tradition, it isn’t easy to date. Historians as near as they can piece together have put it at 1236. But it can just as easily been codified earlier or later. Amselle contends that most scholars familiar with the subject agree that it is either contemporary to or predates the English document.

To learn more about the kingdoms of Sub-Saharan Africa, click here: