Sgt. Pepper Wasn’t Broken. So They Fixed It.

Usually, the re-working and rerelease of a classic recording signifies nothing more than a sneaky cash-grab by either a record company, a producer, a recording engineer, or an artist’s estate (Many of us have assumed a permanent defensive crouch in anticipation of the avalanche of unreleased Prince recordings his estate is sure to authorize.) Why else would you mess with recordings that people already know, love, and own?

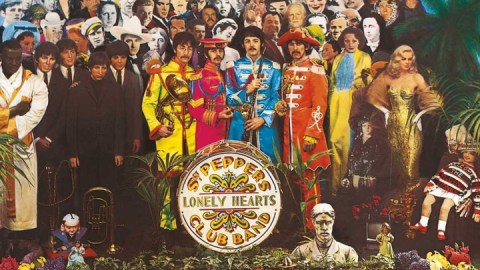

Well, you wouldn’t want a re-painted Mona Lisa, would you? Music and art are things of their time, and should generally therefore be left as is. In June, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the release of their 1967 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles organization released three remixed editions of the landmark album. This time, it’s different. It’s great. To understand why, you have to know a few things about recording technology and what has changed (i.e.: a lot) in the last 50 years.

What’s a Remix? What’s a Remaster? What’s the Point?

Modern recordings are made up of different performances captured at different times and played back together so that they sound like they occurred simultaneously. You could record, say, drums on one track, bass on another, guitar on a third track, and piano on another — when you play them back together, you’d sound like a band. It’s not uncommon for hit recordings to have hundreds of tracks within a “multitrack” recording, with layer upon layer of vocals and instruments stacked into a single musical arrangement.

Screenshot of Pharell Williams’ “Happy” multitrack recording.

Nobody can play a multitrack recording at home or in their car as is. All of those tracks have to be combined — or “mixed” — into a second, listener-playable recording. That’s what you buy, whether it’s a download, a CD, or a vinyl record. The mix may be monaural, which means it’s just a single track containing everything, or stereo, in which the recording’s sounds can be positioned in the space between two speakers. A multitrack can also be mixed into a Surround format, doing the same thing as stereo, but with more speakers positioned around the listener. The majority of modern recordings are in stereo, though in The Beatles’ heyday in England, mono was king. A stereo mix was merely a requirement for other world markets.

Mixing — or “remixing,” which just means redoing a mix — can be an art in and of itself. It involves balancing the relative volumes of the tracks, adjusting their tonal qualities, and adding effects such as reverb and echo. If the recording is the artist’s performance, the mix is the producer’s and the recording engineer’s.

Once the mix is complete, it must be prepared for download, CD, or vinyl. This process is called “mastering.” Depending on how good the mix is, mastering involves either a small amount of tweaking or the last chance for radical tonal or dynamic repairs. Mastering for vinyl is especially tricky given the constraints involved in etching audio signals into minuscule grooves on a spinning disk — if the bass content, for example, is too loud, the grooves collide and the disc is unplayable.

When records are reissued, it’s common to see them advertised as being “remixed” or “remastered.” Now you know the difference. If something’s:

By the time The Beatles became popular, four-track machines were in use in England. Most of the early Beatle hits were essentially performed live, with just a few other layers, called “overdubs,” added later. If the band ever wanted to add more than just a few extra bits, they could copy a mix of the four-track onto another four-track machine — this is called “bouncing” — and then fill up the second tape’s other tracks. In the pre-digital days of magnetic recording, each time the song was bounced, its quality degraded a little, so bouncing was kept to a minimum.

A 4-track recorder used by The Beatles

Beatles and Not-Beatles

The three original Beatles — John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison — had always been ambivalent about continuing as a group. Mark Lewisohn’s excellent Tune In reveals that they disbanded a few times before breaking through. Once there was the possibility, however, of making some real money by performing, the four musicians — having now added Ringo Starr — dedicated themselves to The Beatles business, for how long no one knew. Joined at the hip and caught in a maelstrom of their own inadvertent making, they toured for a few chaotic, non-stop years — with recording sessions squeezed in-between jaunts — before they announced in late summer 1966 that they would no longer be performing.

The four split off into four directions, each one exploring for the first time what it would be like to not be a Beatle. It’s clear that each one of them found the experience both liberating and confusing. After all, they’d been in the band since they were kids. Who were they if not Beatles?

In November, the group reassembled to begin work on a new album, still The Beatles but not quite any more. They looked different, and they felt different. Still, a job’s a job, and in January 1967, they signed a more lucrative recording contract that ensured they would continue being Beatles for a while, whatever that was going to mean.

On the left, August 1966, before quitting the road. On the right, four months later — moptops no more.

McCartney addressed the bandmembers’ identity crisis by suggesting they think of themselves as not The Beatles, but as a fictional group, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. They didn’t have to do teenage-targeted Beatle songs; they could do songs the imaginary band might do. Maybe because not everyone totally bought into the conceit, the idea fell away somewhat as work progressed. Even so, along with producer George Martin, they were a finely tuned recording machine in the habit of topping themselves with each album. Sgt. Pepper was the last time they’d work together so cohesively for an entire album.

The Beatles’ productions had been growing ever-more complex over the course of their previous two albums, Rubber Soul and Revolver, and by the time they started work on Sgt. Pepper, they had to bounce and bounce and bounce to have enough tracks to realize their creative ambitions. As spectacular as the final product was, from a sound-quality standpoint, the earlier tracks — the drums and other basic instruments — had been copied between four-track machines over and over, and sounded like it: thin and small and lo-fi.

Final tape box for the Sgt. Pepper’s song “Day in the Life.” Note track listing on right. (STEPHEN K. PEEPLES)

People may not have noticed within the context of the revolutionary overall sound, but it made the album seem more and more slight, and dated, as time went by.

Why the Sgt Pepper Remix Makes Sense

Unbouncing

With modern equipment, it’s possible to synchronize the original, pre-bounce recordings — in all their pristine glory — so the new remixes basically undo all that bouncing. And boy, does everything sound better: bigger, richer, deeper. Ringo’s drums slam, the vocals are airier, and the resulting clarity is often eye-opening.

Stereo Mono Mixes

Another issue the new mixes rectify is the sloppy manner in which the original stereo mixes were done. The Beatles and their producer really cared only about the mono mixes, and they spent hours, weeks getting them right. The stereo mixes, on the other hand, were tossed off quickly by engineers without the group’s involvement. As a result, the stereo mixes lack a number of careful special touches the band added to the mono mixes, and contain mistakes not found in the mono. Maybe most significantly, the stereo mixes fundamentally misrepresented who The Beatles were.

At its heart, the band was a white-hot little R&B combo. Their club act was made up of R&B and soul chestnuts, many of which appear on their albums. Check out Smokey Robinson’s “You Really Got a Hold On Me” on With the Beatles, for example.

The mono mixes of Beatle albums are muscular, full of an edgy, bluesy, emotional vitality that reflects the band’s ethos. The stereo versions are universally more polite, clean, and soft. The mono “Dear Prudence” from The Beatles, for example, could make you cry; the stereo version is…nice. (Anyone interested in knowing who The Beatles really were is encouraged to get the mono box set of their albums.)

The new remixes were executed by Giles Martin, son of their original producer. With the mono mixes serving as his model for the new version, he has faithfully created, for the first time, a stereo version of the mono mix. Nothing here doesn’t belong. It sounds the same, only different, more exciting, and more alive. And that hot little combo now rocks.

Back to Bassics

Finally, part of the difference between the tame stereo and funky mono releases had to do with issues in vinyl mastering — stereo vinyl mastering was even less tolerant of too much bass than mono: Twice as much audio had to fit into each groove — and the new Sgt. Pepper brings McCartney’s brilliant bass work and Ringo’s bass drum right to the front, where they propel the band as intended.

The 50th Anniversary Value Proposition

The Beatles believed in treating their fans with respect, and always tried to provide value in their releases. From each album’s recording sessions, they extracted a couple of the best songs for release as 45 RPM vinyl singles. This broke with the industry practice of using a throwaway as the second song, and also making sure every album contained the hit. For the Beatles, the accompanying album would not contain the songs on the single since their fans had already bought them — instead, the album would contain all-new, fresh material.

For example, from sessions for:

With Sgt. Pepper and The Beatles, they upped the ante further by including a sheet of cutouts and a custom inner sleeve (Pepper) and a poster (The Beatles)

While re-releases of the band’s catalog have sometimes seemed to be about squeezing additional sales from old product, the three Sgt. Pepper editions feel like a return to form, especially the “Super Deluxe” version.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band 6 Disc Super Deluxe (Anniversary Edition)

There are some albums so pivotal that they merit study by serious students of music and recording. Sgt. Pepper is one such record. The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds is another. For such works, extended editions that reveal the creative process are invaluable as master classes in music and recording.

The “Super Deluxe” edition of Sgt. Pepper is massive, containing four audio CDs, a DVD, and a BluRay disc. These hold the new mix, session highlights, “Strawberry Fields Forever, ““Penny Lane,” alternate versions of a few songs, and video content.

The packaging is beautiful, from an amazing lenticular 3D version of the album’s legendary cover, to the original cutout sheet, the custom sleeve, and a circus poster from which Lennon lifted the lyrics for one of the album’s songs.

If you’re a student of music or recording, or an obsessive Beatles collector, this edition is well worth the money.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band 2 Deluxe CD (Anniversary Edition)

This two-CD set includes the remixed album and single, as well as a handful of session highlights. Really, the reason to buy this is if you want the fresh mixes of “Strawberry Fields Forever”/“Penny Lane” as well as Sgt. Pepper.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band CD (Anniversary Edition)

This CD contains the new remix of the album. If you’re just interested in hearing a powerful, fresh reissue of The Beatles’ classic album, this is the one for you.

It must be said: A splendid time is guaranteed for all.