This Is How You Can Become a Damn Good Writer

The rhythm of a good sentence moves through you as powerfully as a solid beat. It can cause you to fall silent, placing the book face down, pages spread, to contemplate the vast sweep of life, all thanks to the combination of a few simple words. It can call you to action, creating a swell of motor neurons dictating forward momentum. A dopamine cascade tingling the extremities of limbs and minds when the puzzle pieces of language fit together in just the right form.

Sentences arrive in a flash of inspiration yet might be labored over for weeks, months—the path to fiction is not easily distracted or hopelessly inattentive. Writers spend hours typing words like musicians play scales, writes literary theorist Stanley Fish in his book, How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One. The subtitle is telling. A writer needs to be a reader, to help grapple with the myriad forms available. Storytelling is architecture. From few basic materials a landscape of diverse structures emerges.

Know What You Want to Say

Forms not only allow us to discover a common foundation to build on top of, Fish continues, but are “the very possibility of meaning.” To discipline yourself in form is to practice a discipline of thinking, which is why Fish believes writers are not copyists, but selectors. That includes not only the words you choose, but the breadth of the story you’re trying to tell.

The goal is not to be comprehensive, to say everything that could possibly be said to the extent that no one could say anything else; if that were the goal, no sentence could ever be finished. The goal is to communicate forcefully whatever perspective or emphasis or hierarchy of concerns attaches to your present purposes.

Know the Power of a Sentence / Collect Sentences that Move You

Take, for example, one of my favorite sentence writers, Jorge Luis Borges. In Labyrinths, he writes:

Thus the days went on dying and with them the years, but something akin to happiness happened one morning. It rained, with powerful deliberation.

Borges masterfully strings readers along with a necessary tension, leading you one way then the other, words like a bow massaging the violin’s strings. There is movement, which New Yorker writer James Wood believes to be an essential component of writing. In How Fiction Works he tells of a writer who opens a novel with an old photograph, a tired cliche immediately signaling “that the novelist is clinging to a handrail and is afraid of pushing out.”

To Move Your Reader, Write with Movement

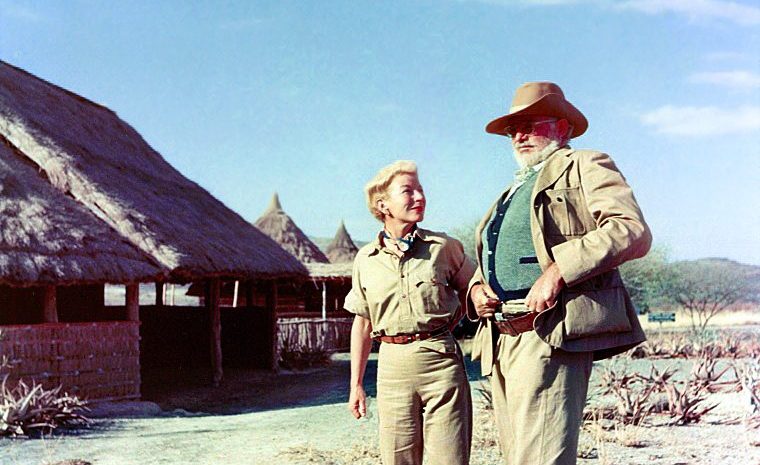

The photograph is a representation of life, as are words. The Buddha in his meditative repose; Jesus in contemplative and compassionate earnestness. Historical characters are at constant risk of becoming caricatures, a trend that continues today when Instagram “stars” only show one side of their personality, over and again. When we focus on only one aspect of their being, as we often do with photographs, we forget they’re complex, multifaceted beings.

The images of the prophets above are aspirational yet not wholly representational. No sign of the tears, confusion, and uncertainty that over time gave clarity to the shape of their molds. Wood believes the same trap happens with amateur novelists, who rely on static descriptions of what should be dynamic beings. For him, more practice, and patience, is required.

The unpracticed novelist cleaves to the static, because it is much easier to describe than the mobile: it is getting these people out of the aspic of arrest and mobilized in a scene that is hard.

Make the Everyday Seem Extraordinary

Speaking of his first volume of published poetry, Pablo Neruda admits he never wanted mystery or magic to infiltrate his observations. In Memoirs, the poet, he maintains, must in personal effort help everyone reach higher. In doing so he caresses everyday objects, grounded in the commonplace, the key to transcendence. Neruda says:

The closest thing to poetry is a loaf of bread or a ceramic dish or a piece of wood lovingly carved, even if by clumsy hands.

Fish puts it nicely: “What you can compose depends on what you are composed of.” There is an artificiality to language, in that words are units we inhabit and manipulate in order to carry meaning across. They are not real yet represent everything in reality. So powerful is writing you might believe its invention signaled metaphysical representation, but you’d be wrong.

Understand What a Word Really Is

Despite romanticized myths of gods handing down language to animals with engorged cortices, Felix Martin points out in Money: The Unauthorized Biography that writing, for thousands of years, was merely accounting. You have this many cattle; my land yields this many bushels of wheat. These symbols, which eventually became written words, represent the thing without actually being the thing.

When Neruda claims the strength of words resides in the mundane, he was unknowingly tapping into the origins of language. Symbols we call letters were invented to keep track of bread and dishes. From there we gave such objects life through the expanding associations and possibilities of our newfound muse: the creative potential of narrative.

From the pragmatism of credit we’ve created literature, exploiting certain brain regions while embellishing others—literature engages the visual cortex, hippocampus, and default mode network, and can even send readers into flow states by disengaging parts of the prefrontal cortex associated with self-awareness. Love of structure collided with passion for narrative. It took millennia but scribes eventually turned loaves of bread and ceramic dishes into poetry. The everyday became transcendent. The evolution of written communication armed us with innumerable vehicles of imagination to transform daily events into extraordinary occurrences.

Breathe New Life into the Oldest Story in the Book

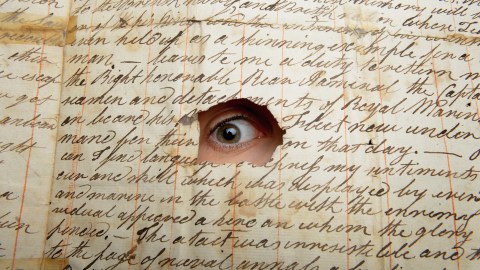

What comes through in all of these writings on writing is the journey: humans are seeking animals. First, the basics: nutrition, enclosed shelter, other bodies to fulfill biological impulses and share emotional quandaries with. From there, the story.

For Wood, storytelling requires a constant urge that something new, something greater, always lies in wait around the corner, regardless of the few basic tales—of war, of love and love lost, of deception and power—we keep repeating with different characters, over and over throughout the ages. We must act as if the dull edges of repetition have fully hypnotized us, then rebel against it with all our might.

The true writer, that free servant of life, is one who must always be acting as if life were a category beyond anything the novel had yet grasped; as if life itself were always on the verge of becoming conventional.

—

Derek is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles, he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.