Religion, and the mentality it brings, have arguably shaped the human species more than any other force. We don’t understand it, and perhaps never will. We are so far removed from religion’s creation (pun presented but not intended) that we have instead just woven it into our daily lives and accepted it as something we can’t understand. This leads to questioning, mostly about what religion actually is and what is the “right” one. But instead of asking “what” religion is (e.g. is there a big man in the sky who lives in a cloud, or egads maybe that crazy science-fiction author L. Ron Hubbard had it right after all?!), perhaps we’re asking the wrong question. Children seem to be born with an innate understanding of “souls” or at the very least the semblance of self amongst something greater – posits Reza Aslan – and this knowledge that religion is based on a literal primitive instinct should allow us to understand the question of “why” religion is. If you go back far enough, Reza says, you can pretty much pinpoint various reasons as to why religion is. It’s an interesting video, and one that is sure to have you thinking about the subject matter much later. Reza’s latest book is God: A Human History.

Reza Aslan: Studies of children have shown that we are born with this instinct for what’s called “substance dualism,” the idea that the body and the mind or soul, however you want to think of the psyche, are separate.

Children who as young as three or four years old, who have not grown up with any kind of religious instruction, naturally assume that they have a soul.

And so I think a lot of theorists believe that this belief in the soul is universal, that it can be traced back deep into our evolution. Why? There’s a whole host of reasons for that: I mean I suppose that if you’re an “unbeliever” you think that it’s just some kind of evolutionary accident—It’s a trick of the mind, as it were, that makes you think that you are an immaterial being inside a material body.

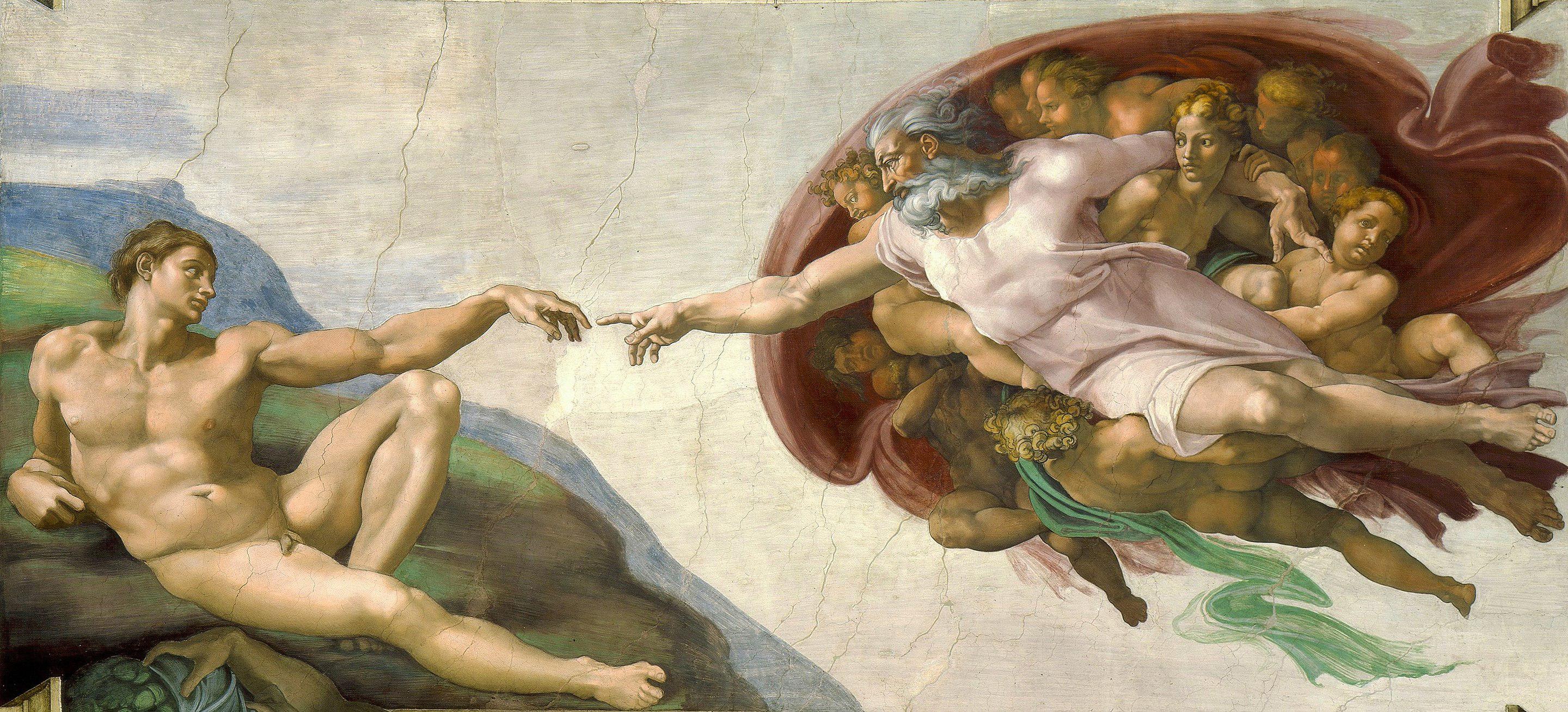

If you’re a believer you think that it’s probably because there is a soul and maybe perhaps that we were intentionally created in such a way as to think that there is more to us than just the material realm.

It’s really a choice, but what cannot be denied is that belief in the soul is a belief that all peoples share regardless of their culture or their religion. And it’s a belief that goes back as far back in time as we can possibly trace it. And if these psychological studies that I was talking about are right, it’s a belief that we’re born with.

Over the last couple of hundred years, there’s been an enormous amount of thought that’s gone into the question of “why religion?”

You know the one thing that we all agree on is that religion has been a part of the human experience from the beginning.

In fact, we can trace the origin of religious experience to before homo sapiens. We can trace it with some measure of confidence to Neanderthals. We can measure it with a little less confidence all the way to Homo Erectus. So we’re talking hundreds of thousands of years before our species even existed. So the question is why?

If religion is a universal phenomenon—or rather I should say religious experience—If religious experience is a universal phenomenon, if it can be traced in all peoples, all cultures and throughout all time, then there must be some evolutionary reason for it. There must be a reason. Some adaptive advantage to having a religious experience or faith experience. Otherwise, it wouldn’t exist.

And so there have been over the last couple of centuries numerous attempts to figure out exactly what that adaptive advantage would be. The most popular explanation, of course, is the sociological one: that religion creates a sense of cohesion amongst a group. And that sense of cohesion, the idea that we could come together and create a collective identity based on shared symbols or shared metaphors gave an adaptive advantage to believing communities that non-believing communities did not have.

That’s a pretty good answer. The problem is that religion is as much a divisive issue as it is a cohesive one. It’s as good at creating outgroups as it is in groups. And more importantly, the problem with the social cohesion theory is that kinship was a much more powerful and much more dominant form of social cohesion than religion was.

Our ancestors lived in small communities that were bound together by blood, by relationship, by kinship long before they created symbols and mythologies in order to unify them. So it’s a pretty good answer, but it doesn’t really explain what adaptive advantage religion would have had.

Others have said well, it’s about giving us answers to the unanswerable questions of the world, that what it did was create a sense of knowledge about the universe that lessened anxiety in some way, and that was an adaptive advantage.

Well even if that were true—and there’s truly no reason scientifically to think that it was—it’s really hard to make an argument about why that would necessarily be an adaptive advantage, particularly because religion actually causes far more anxiety than it lessens.

In fact, to put it in evolutionary terms, the cost of religious expression is enormous. It’s enormous in terms of time, it’s enormous in terms of the cognitive processes that are involved in it. It sort of creates greater anxiety when you feel as though your actions have cosmic significance. All of this is to say that the countless different answers that have been given for “Why religion?” fail primarily because they’re functionalist answers.

What they primarily say is what religion does, not why religion exists.

And so a group of cognitive scientists, particularly cognitive scientists who focus on religion, have tried to look to a different way of answering this question of “why religion?”

And what they discovered is that number one, there is, in the end, no adaptive advantage to religious faith.

And number two, that the reason that religion exists is because it is an accidental byproduct of some other adaptive advantage.

And here we get into very complicated conversations about cognitive theory and the development of our frontal lobes and things like that. But to put it in its simplest way, religious thinking is embedded in our cognitive processes. It is a mode of knowing. We’re born with it. It’s part of our DNA.

The question then becomes why? One answer is that there is no why. It’s just simply an accident of other much more important, much more necessary cognitive adaptions—adaptations, I should say.

Or if you’re a believer you would say because we were made that way. Because we are designed to believe that there is more to this world than the material realm. That that mode of knowing that exists in our brain is there for a reason. Either answer is fine.

There are some people who say well, what religion really does and the reason that it exists is that it creates some morality, right? That if we imagine that there’s this absolute moral lawgiver then we’re less likely to kill our neighbor, and that creates some sort of adaptive advantage.

The problem with that theory, of course, is that the concept of a moral lawgiver is barely 5,000 years old, and religious expression goes hundreds of thousands of years.

I mean if you even think about the Mesopotamian gods or the Egyptian gods—and this is again 7,000 or 8,000 years ago—these were not moral beings. On the contrary, they were amoral and often immoral beings!

So the idea that religion is about morality is a very new idea.

Others say that religion is about authority. It’s a way of maintaining control and power over a group, and perhaps those groups that were religiously inclined had an adaptive advantage because that notion of an authority structure allowed them to survive better. Again, that’s a pretty good answer. The problem is that you’re talking about institutionalized religious expression, which maybe, maybe is 12,000 to 14,000 years old. That’s as far back as we can trace anything that looks like an institutional religious authority. And again that does not explain why religion existed hundreds of thousands of years before that.

The truth of the matter is we just don’t know.

But what is a fact is that there is something in the way that our brains work that compels us to believe that we are more than just the sum of our material parts. That thing is either an echo or an accident, or it’s deliberate and purposeful.

And which you decide is purely a matter of choice because there is no proof either way.