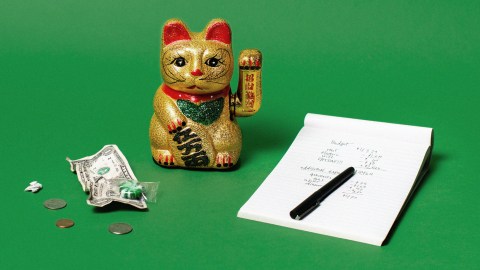

Kakeibo: The Japanese way to manage money through mindfulness

- Money should facilitate a meaningful life, not control it.

- Kakeibo is a budgeting technique to help people be mindful of where, how, and why they spend their money.

- By understanding your life values and financial goals, you can boost your confidence and motivation in achieving your money goals.

We can sometimes approach household finances as a cold math problem. You start with a fixed income. You pay your bills and utilities, maybe save a small percentage, and finally spread out the remainder to see you through to next month. Plug in the numbers, do the operations, and you’re done. Budget budgeted!

But this approach has a major flaw: It puts math before mindfulness. That’s a problem because finances are math problems complicated by the variables of human psychology.

Every day, we face a seemingly infinite number of ways to spend our finite incomes on our many — always competing and often contradictory — needs and wants. Do you splurge this weekend on a meal out or cook at home? Is your closet looking too dated or ratty for the office? Do you service the car today or set aside that money for your next doctor’s visit (just in case)? And those don’t even consider the challenge of saving for retirement, a house, and the kids’ college fund. There’s just not enough to go around, and the perceived importance of those needs and wants can shift at any given moment.

Overwhelmed by this cognitive load, many people find themselves gravitating to the extremes. Either they save themselves the stress and make purchases mindlessly, or they micromanage their finances to the point that they are living for the ledger. Far better is to find the balance between the extremes, and one method for doing that is the Japanese budgeting technique of Kakeibo.

Kakeibo helps people to see past the extraneous to reveal the essence of what their finances are and how to use them. It does this by showing users not only what they are doing with their money, but how they can use that money to spend well, save well, and, ultimately, live well.

Before the math, mindfulness

Kakeibo (pronounced “kah-keh-boh”) was developed in 1904 by Hani Motoko, Japan’s first female journalist and later a publisher of a woman’s monthly magazine. Motoko wanted to help the women of her day, who often lived on a limited budget, meet their life and savings goals. To that end, she created a budgeting system that combines utility, simplicity, and mindfulness.

Even Motoko’s chosen name betrays this intent: Kakeibo means simply “household account” in its native Japanese.

Kakeibo starts with a mindfulness exercise. Before you even crack the spine on your first ledger, the technique asks you to consider four self-reflective questions. They are:

- How much income do you make a month?

- How much would you like to save?

- How much are you currently spending?

- Where would you like to improve?

These questions not only create financial goals but also point to what financial advisor Paula Pant calls “first-principles thinking.” In terms of budgeting, first-principles thinking means considering the values you want in your life and how you might cultivate them. It’s the realization that money is a means to facilitate a satisfying life — not a series of tactics and strategies aimed at controlling it.

According to Pant, this requires us to accept a basic truth. That being: You can afford most things if you plan and save, but you can’t afford everything. As she told us in an interview:

“You can’t have an endless series of ands. You might not be able to have that thing and something else and something else and something else. And that doesn’t just apply to your money. That applies to your time, your focus, your energy, your attention – any limited resource. And life is the ultimate limited resource. So when you practice being better at managing your money, you practice being better at managing your life.”

Finance advisor and Kakeibo proponent Harumi Maruyama expresses a similar perspective, albeit a little more forcefully. As she told the BBC: “Money is not limitless. It has limits. It’s totally up to you whether you save it or lose it.”

The four categories of Kakeibo

After accepting that truth and getting clearer on your first principles, it’s finally time for math.

At the beginning of the month, calculate your projected income and subtract your fixed costs (things like rent, utilities, and other bills). Anything that remains is how much money you have to spend or save that month. Then every time you spend money, write it down in your ledger and label it as one of four categories:

- Essentials (gas, toiletries, and groceries).

- Non-essentials (movies, restaurants, and spa days).

- Culture (books, museum visits, education, and charity).

- Unexpected (doctor visits, car repairs, and a gift for that friend’s birthday you totally forgot).

Why do this? A potential trap of some budgeting systems is to create many fine-grained categories believing they will increase accuracy. There’s a category for groceries, one for restaurants, one for repairs, one for gas, one for clothes, one for books, and so on. However, the end result of this approach is unnecessary confusion that obscures your spending mindset.

By bucketing your spending into these four categories, you simplify your budget so you can see the big picture. If your new shoes are for fun, they go in the non-essentials category. If they are a job requirement, they go under essentials. This way, you can be as mindful of how you’re spending your money as what you’re spending your money on.

Most Kakeibo proponents also recommend using a handwritten ledger to track your expenses throughout the month. They point to research suggesting that when we write something by hand we retain the information better and create a stronger connection with the content. Others use a spreadsheet app for its ability to search for specific entries, group categories, and make graphs of their spending quickly and easily.

When you practice being better at managing your money, you practice being better at managing your life.

Paula Pant

Whether you go with a handwritten ledger or a digital one — I won’t tell if you don’t — just ensure it’s a method you will use. You want your ledger to contain all of your monthly expenses, and you want to be in the habit of entering your spending regularly (for example, nightly or at the end of the week).

At the end of the month, you’ll review your spending. Calculate how much you spent in each category as well as how much you saved. Then compare the results to the goals you set for yourself.

- Did you save as much as you thought?

- Did certain essentials slip your mind in your original assessment?

- Did some of your non-essential purchases seem unnecessary in hindsight?

- Did any unexpected purchases come with unexpectedly high price tags, too?

If you reached your savings goals, great! If you didn’t, that’s also fine. There’s no reason to feel shame. You can’t win or lose your at finances, nor are they a social competition like a video game-style leaderboard. Rather, you should view your ledger as data and your mistakes as lessons to inform better decisions next month. Maybe you need to cut back on some non-essential purchases to save more. Conversely, maybe your savings goals were too aggressive, and you need a few more non-essentials to destress on the weekend.

Whatever your ledger reveals to you, you can return to the four questions and answer them in light of your new knowledge. As a bonus, research shows that tracking your expenses promotes confidence and relaxation, which in turn motivates us to achieve our goals.

Find your financial balance

Underlining Kakeibo is a Japanese philosophy of life called nagomi. While it doesn’t have a direct translation, it’s centered on the concepts of balance, harmony, and sustainability and how to bring those qualities into life’s endeavors.

In his book on the philosophy, Ken Mogi writes that “[nagomi] is not about finding shortcuts to happiness, success, or wealth; it is about understanding and enhancing the good and positive aspects of our lives to balance the difficulties that inevitably befall everyone one of us.”

Kakeibo asks you to do the same with your finances. This is why it includes a special category for culture. The method recognizes that your life shouldn’t be chained to your finances. Rather, your finances represent a resource — one of many — that cultivates growth, learning, and meaningful life activities.

And while I’ve written about Kakeibo as an individual technique; in fact, it has had many different iterations since Motoko first devised it a century ago. It’s also highly adaptable. Maybe you find that you need to add a fifth category, or that you need to create your own savings categories, or that you spend so much on books it’s best to consider them separate from other expenses. That’s fine as long as those changes support your first principles.

However, by taking the time to shed the extraneous and focus on the essence of your finances, you avoid the over-optimization trap while also making your budget feel manageable and motivating. This will help you spend in a way that allows for a mindful, meaningful life in the here and now while saving in a way that ensures the same for your future.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Paula Pant’s full class for your organization, request a demo.