A physician didn’t shower for 5 years. Here’s what he found out

- For his new book, Clean: The New Science of Skin, physician James Hamblin didn’t shower for five years.

- Soap is a relatively simple concoction; you’re mostly paying for marketing and scent.

- While hygiene is important, Hamblin argues that we’re cleaning way too much — to the detriment of our health.

A few months ago, James Hamblin made a splash when announcing he hadn’t showered or used much soap in five years. The physician, Yale public health lecturer, and staff writer at The Atlantic experimented on himself as research for his latest book, Clean: The New Science of Skin.

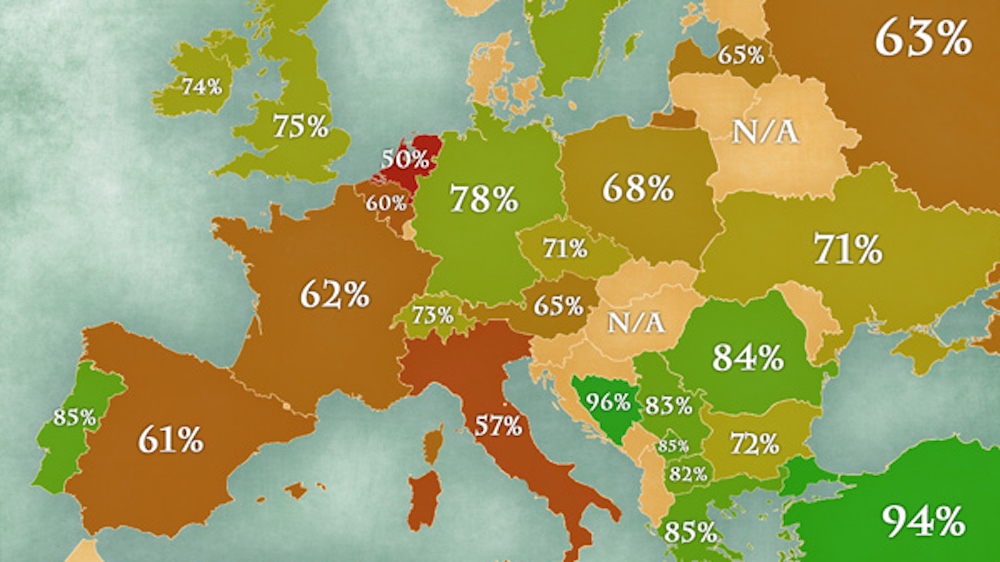

Hygiene rituals are as old as recorded civilization. While Muslims and Hindus created elaborate cleaning rituals, European Christians thought bathing increased your chances of falling ill thanks to miasma theory. For centuries, changing your linen shirt supposedly bestowed cleanliness — not soap and water. Many Christians during this era only had one bath in their entire lives: baptism.

Though we certainly want to wash more often than once a year, Hamblin points out that many current hygiene and skincare rituals have moved us too far in the opposite direction. In fact, our expensive rituals may be more harmful than helpful. Additionally, modern hygiene and skincare is a time suck. As Hamblin points out, if you spend a half hour showering and applying products every day, you will devote over two years to grooming-related activities over the course of a century-long life.

In his previous book, If Our Bodies Could Talk, Hamblin investigated numerous body myths. In Clean, he focuses on our largest organ. Skin is an environment unto itself. What follows are six important lessons in his book, ranging from hygiene to greed.

#1. An obsession with soap might be creating allergies

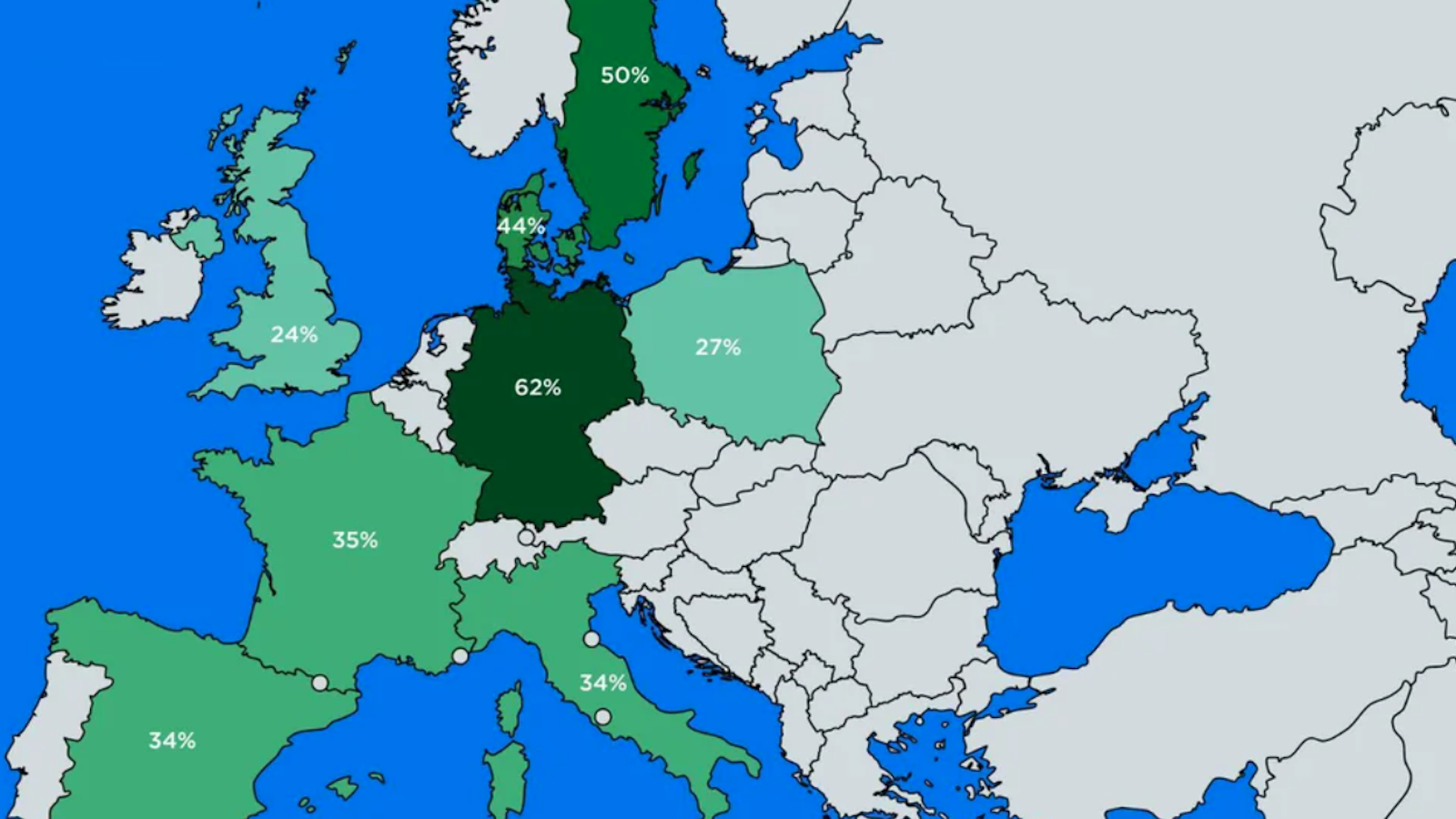

In the quest to protect our children against bacteria, we might inadvertently create lifelong allergies. An uptick in peanut allergies is indicative of this trend. Our skin is the first line of defense against disease, and it knows how to protect itself. The organisms and bacteria that live on our skin are doing important work; the more we wash them away, the more susceptible we become to foreign invaders.

Nut allergies might only be one consequence of overwashing. Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and eczema might in part be caused (or provoked) by too many antibacterial soaps (or soap in general). As Hamblin writes, “Soaps and astringents meant to make us drier and less oily also remove the sebum on which microbes feed.”

#2. Your skin is crawling with mites

Speaking of foreign invaders, skin science supports an old Buddhist idea: There is no self. As Hamblin puts it, “Self and other is less of a dichotomy than a continuum.” In fact, “you” are a collection of organisms and bacteria, including the mite Demodex. A half millimeter in length, these “demon arachnids” are colorless and boast four pairs of legs, which they use to burrow into the skin on our face. Yes, your face, too.

While these mites were originally discovered in 1841, it wasn’t until 2014 that a group of researchers in North Carolina used DNA sequencing to understand their impact. Though you might recoil at the suggestion, it turns out that these critters potentially act as natural exfoliants. While housing too many of these mites results in skin disease, your face is their home. If not for them, you might even be more susceptible to breakouts and infections.

#3. Soap benefited from ingenious marketing

Soap is chemically simple. Combine fat and alkali to create surfactant molecules. The fat can be animal- or plant-based — three fatty acids and a glycerin molecule create a triglyceride. Combine this mix with potash or lye, apply heat and pressure, and wait for the fatty acids to rush away from the glycerin. Potassium or sodium binds to fatty acids. That’s soap.

What you’re paying for are the scent and packaging. In 1790, the first patent in history was approved for an ash processing method that produced soap. It wasn’t an immediate hit; the balance was off. Too much lye resulted in a lot of burnt skin. A century passed before companies convinced Americans regular washing was necessary. Thanks to ingenious marketing — we still have radio-inspired “soap operas” today, though barely — soap became a must-have. A luxury became a common good.

Marketers convinced the public that everyone should buy a lot of soap. As Hamblin phrases it, “Capitalism sells nothing so effectively as status. And if a little bit was good, a lot would be better.” Soap infected mainstream consciousness.

#4. The skincare industry is largely unregulated

Hamblin tried another project for this book: He launched a skincare line. One day, he went to Whole Foods and purchased raw ingredients: jojoba oil, collagen, shea butter, and a few other things. After mixing them in his kitchen, he ordered glass jars and labels from Amazon. In total, he spent $150 (which included his company website) to launch Brunson + Sterling. He then posted two-ounce jars of Gentleman’s Cream for $200 (on sale from $300!).

Hamblin didn’t sell any jars, but that wasn’t the point. At an expo, he noticed one-ounce jars of SkinCeuticals C E Ferulic selling for $166, even though that topical acid is no more effective at improving health than eating an orange. Collagen is another hype machine. Drinking collagen does nothing for your skin as it’s broken down by enzymes in your digestive tract. Even so, plenty of companies claim it gives you glowing skin.

Even more incredibly, Hamblin didn’t have to report any ingredients to the FDA. He also didn’t need to note its effects or provide evidence of safety. All he had to do was apply for a business license. The FDA can’t even make him (or anyone) recall products. The government’s safety system relies on a code of honor — and there are plenty of businesses that are less than honorable.

#5. Disinfectant decoy

Do we really need to wipe everything down with Clorox? Probably not, Hamblin suggests. In fact, for Clorox to work, you have to leave it on the surface for about ten minutes. He says, “The product isn’t ‘killing 99.9% of germs’ in the way that anyone actually uses it — a quick wipe-down.” Instead, clean your countertop with soap and water.

Besides, regularly killing every “germ” in the environment isn’t the healthiest practice. “Some chronic conditions seem to be fueled by the fact that so many of us are now not being exposed to enough of the world,” Hamblin writes.

#6. Animals smell — and you’re an animal

The soap advertisements that kicked off modern marketing relied on one concept: B.O. We think of body odor as a given, but that too is an invention. Our feet “smell” thanks to bacteria like Bacillus subtilis, which has potent antifungal properties. Shoes weren’t available for most of history, a period in which smelly feet bestowed a strong evolutionary advantage. As Hamblin writes, we didn’t evolve to smell; we evolved in harmony with protective microbes that we just happen to find unpleasant.

While a number of players in the wellness and skincare industries likely have good intentions, so much of what is sold is unnecessary, and even damaging. The marketing machine makes us feel incomplete — so we have to buy products that make us feel whole. As Hamblin concludes, evidence-based companies would take an opposite approach to skincare and hygiene: less is more. But that slogan doesn’t sell a lot of soap.