Whose Art Is It Anyway?

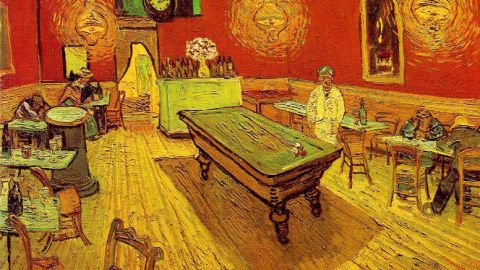

The fight over who owns art might have just gone nuclear, and Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 painting The Night Cafe is at the center of it. The descendents of the Russian industrialist who bought the painting in 1908, only to see Soviet Russia “nationalize” the painting and sell it in the 1930s, are demanding that Yale University, which received the painting as a bequest in the 1960s, give it back. Perhaps $20 billion in art treasures hangs in the balance. Who is right? What does this mean for the public, who can only stand on the sidelines as masterpieces have their day in court?

It’s hard to deny the rights of Pierre Konowaloff, great-grandson of Ivan Morozov, who bought The Night Café in 1908. And yet, Yale has taken care of Van Gogh’s work for almost half a century now, conserving the work and exhibiting it to the public. Much of the value of The Night Café comes from the efforts of Yale. Should that value be completely discounted? Van Gogh’s work belongs to the ages and all people, so the idea that a single person could take it home and hang it on the wall seems wrong in a profound way.

But, of course, these battles are rarely just about a family trying to regain their property wrongly taken. Take the example of Gustav Klimt‘s 1907 painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Taken by the Nazis from the rightful Jewish owners, the painting fell into the hands of the Austrian government after the war. The surviving family members fought the Austrian authorities for the painting, finally winning it back in 2006. As soon as they had it in their hands, however, they sold it for $135 million to Ronald Lauder, who added it to his collection at the Neue Galerie in New York City. Lauder had helped the family pay the legal bills involved in the restitution. Once they got the painting back, the family was unable or unwilling to pay the taxes on the painting and rolled it over to Lauder, who had positioned himself to be first in line for the painting.

Because of legal restrictions imposed by the Austrian government over their artistic heritage, paintings by Klimt almost never hit the open market. Restitution represents a loophole around those laws. I’m not saying that the family didn’t deserve to get their heritage back or that Lauder didn’t have noble motives in his assisting of the family, but there is a great temptation to use restitution to put famous works by famous artists such as Van Gogh back on the market.

Imagine for a moment what that could mean? Nearly the entire Louvre came from the thievery of Napoleon. The British Museum has been clinging to the Elgin Marbles for dear life for decades. Egyptology departments of every museum in the world quiver when Zahi Hawass calls. Large swaths of the modern art collections of American museums are there thanks to the fire sale of “degenerate art” by the Nazis on the eve of World War II. If all that art were to be suddenly up for grabs in courts, with legitimate claimants bankrolled by parties looking to score an Old Master previously beyond reach, the art collections of the world could suddenly become a game of masterpiece musical chairs.

There is no easy answer to this issue. Perhaps a least worst solution would be to compensate the families while allowing the museums to retain the works they have worked so hard to preserve and promote. Anything less might mean a Wild West atmosphere in the world of art history in which we’re all losers.