From Beowulf to video games: Why slaying monsters is such an existential bummer

- Monsters have always represented societal fears.

- We typically experience monster stories as triumphs over adversity, yet stories over the centuries have also questioned this view.

- From Beowulf to Gothic literature to video games, monster slayers are often tainted with the fears and monstrosities they hope to overcome.

Fictional monsters have always reflected real-life societal fears and anxieties, but the rapidly changing world around us makes it difficult to say where the monster is — and in fact, the monster may be ourselves. This makes the traditional monster narratives of clear-cut heroes slaying clear-cult monsters feel very outdated. There are several ways of challenging traditional monster narratives. Besides making the monsters sympathetic (which games like Undertale have done with great success), one can also cast doubt on the heroism of the monster slayer.

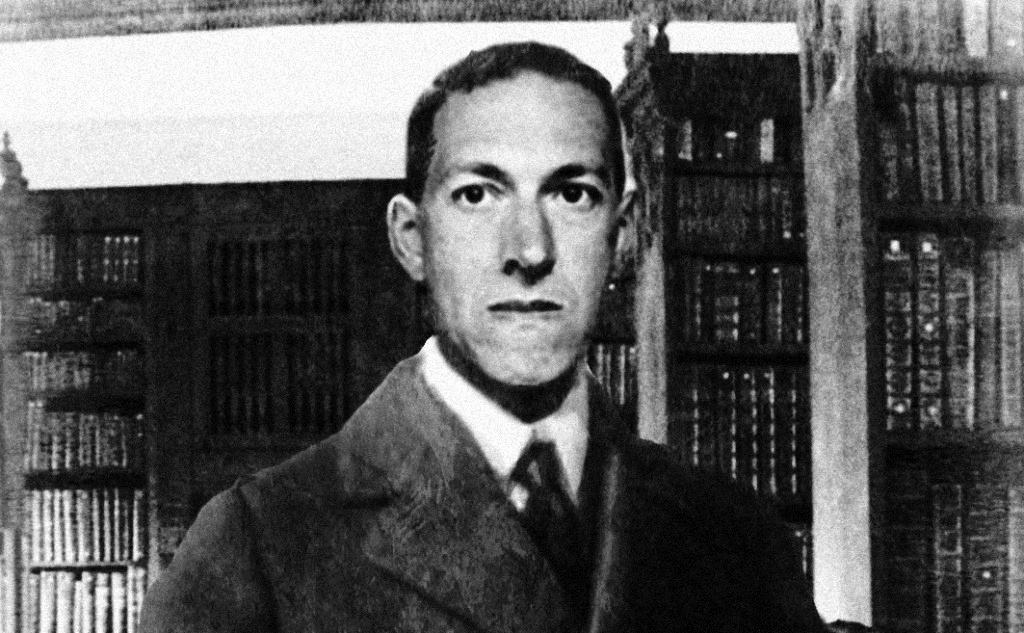

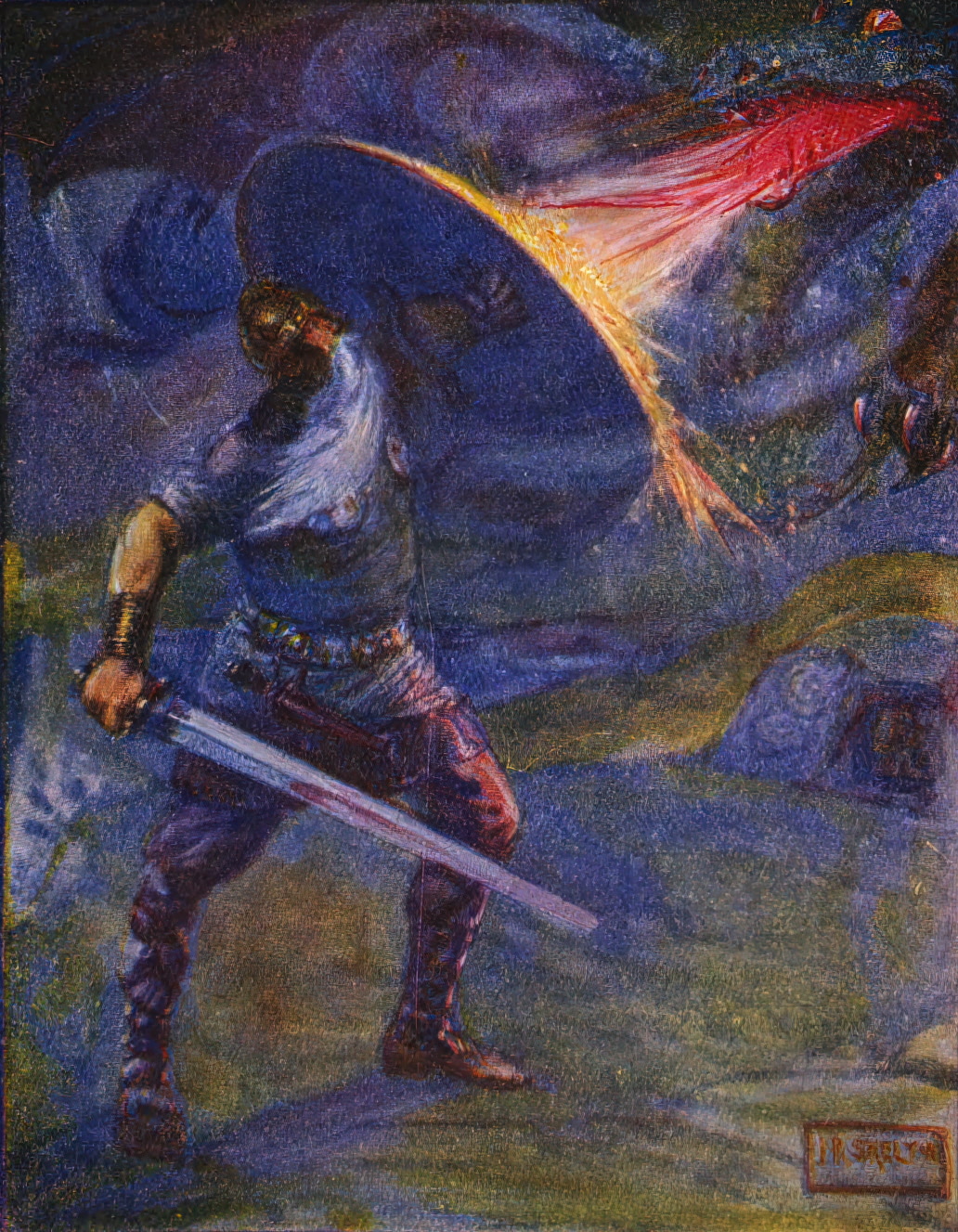

In the Western tradition, the latter line of thinking far precedes the 20th century and can be identified in early Christianity. One of its most famous formulations appeared in the 1936 essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” by J. R. R. Tolkien. Tolkien argues that monsters are critical to understanding the poem’s poetic qualities. In his view, they provide a perspective that “surpasses the dates and limits of historical periods” — in other words, they evoke a sublime feeling of timelessness. At the same time, he makes it clear that killing monsters should not be understood as inherently virtuous. He sides with the poet of Beowulf in rejecting the notion of “martial heroism as its own end.” Despite his ever more difficult exploits, the proud warrior Beowulf faces the “tragedy of inevitable ruin” that no earthly fame or fortune can prevent. Although he kills the dragon — the poem’s final “boss” — he is mortally wounded and dies soon afterward.

Tolkien’s approach to Beowulf’s heroism stems from his Catholic faith, which informed both his academic and fiction work (perhaps with the important exception of his surprisingly one-dimensional portrayal of orcs as an evil race in The Lord of the Rings). As summarized by Asma, Tolkien adopts the early Christian view that “without Christianity, monster killers are either hopeless existential heroes, trying by pathetic human effort to rid the world of evil, or they are themselves monstrous giants amid a flock of righteous and meek devotees.” Accordingly, Tolkien reads Beowulf as a tragic hero, concluding that the poem is an elegy rather than an epic.

Tragically portrayed monster killers are not uncommon in popular culture. As pointed out by the game scholar Tanya Krzywinska, the theme of a “false hero,” handed down from Gothic literature and film, is typical of horror and fantasy video games. The somber, elegiac tone colors many titles that employ the “player vs. environment” model while simultaneously questioning it. A prime example of such a game is Shadow of the Colossus (2005), widely acknowledged as a milestone in enemy design and ethical gameplay. Its story follows a young man named Wander who travels into a forbidden land to bring his dead lover back to life. An unseen, mysterious entity tells Wander that in exchange, he must slay sixteen colossi — gigantic creatures that inhabit various corners of the land. To defeat them, Wander must identify and reach one or more of their weak points (or “vitals”). Unsurprisingly for an action-adventure game, each colossus poses a unique puzzle, inspired by the bosses of the Legend of Zelda series. Shadow of the Colossus, however, departs from the formula in at least three aspects.

First, there are no “mobs” (or weak, fodder-like enemies) in the game. The reasoning behind this decision was both practical and artistic. As the game’s producer Kenji Kaido said in an interview, they did it “so the team’s resources could be concentrated on the [colossi],” but also to underline the “contrast between the quietness of traveling and the fighting.” As a result, the game offers no easy satisfaction of hacking and slashing through weaker opponents.

Second, Wander can — and often must — scale, balance on, and hold onto the monsters, often by grabbing onto their fur. As Kaido pointed out, “they are part building, and part living creatures.” A colossus is not merely an opponent the protagonist fights, but it is also the ground on which he stands. When the colossi try to shake him off, Wander becomes quite literally an unstable subject — he spends long minutes pressed against the monsters, temporarily merging with their body mass before stabbing them with his magic sword.

Finally, the destruction of colossi is framed as ethically questionable. In a retrospective interview, the game’s director Fumito Ueda reminisced that throughout the production of the game, he “started having doubts about simply ‘feeling good by beating monsters’ and ‘getting sense of accomplishment.’” The colossi are largely peaceful until Wander attacks them. Although the player may experience triumph when beating them (and, in the 2018 remake, collect PlayStation trophies for each), the game’s audiovisual design suggests the exact opposite. When stabbed by Wander’s sword, they roar and writhe in pain as black blood sprays from their wounds, and their eventual demise is accompanied by melancholy music. To illustrate how unusual this was at the time, Ueda recounted that when he first showed the music to his staff: “They thought it was a bug and laughed because they were so used to games that would play a fanfare after defeating a monster.”

From the outset, Wander’s nightmarish quest is portrayed as futile and senseless. The Japanologist Miguel César situates the game’s narrative in a longer history of representations of what he calls “essential boundary transgressions” between life and death in Japanese folk and popular culture. In his view, “all its mechanics, the design choices and narrative work in that direction: to convince the players of how wrong and dangerous the [transgression] is, even if the game is forcing them to do it.” Wander’s boundary transgression is shown as an “immoral selfish act,” but the player has no choice but to push on and witness Wander’s inevitable ruin.

While Shadow of the Colossus is deeply rooted in Japanese rather than Western Christian culture, it aligns with Tolkien’s observation about the inherent tragedy of monster killers whose motivations are selfish rather than morally just. It also sends an environmental message, casting doubt on the need to tame and neutralize the forces of nature, represented by the colossi.

Shadow of the Colossus, of course, is not the only game to question the conduct of the monster killer. Bloodborne and Dark Souls (whose spectacular monsters are likely inspired by the colossi) also present fighting monsters as a dreadful, melancholy affair, equally tragic for everyone involved. In a telling anecdote, these games’ director Hidetaka Miyazaki — well known for creating “sad” monsters — asked a concept artist to redo a gross-out design for an undead dragon with the instruction: “Can’t you instead try to convey the deep sorrow of a magnificent beast doomed to a slow and possibly endless descent into ruin?” All three games suggest that the plight of the monster killer is inseparable from the plight of the monsters, an observation famously summed up in Friedrich Nietzsche’s aphorism: “Whoever fights with monsters should see to it that he does not become one himself. And when you stare for a long time into an abyss, the abyss stares back into you.”

While Shadow of the Colossus is deeply rooted in Japanese rather than Western Christian culture, it aligns with Tolkien’s observation about the inherent tragedy of monster killers whose motivations are selfish rather than morally just.

– Jaroslav Švelch

This theme resonates with the experience of learning the monsters’ mechanics to defeat them, which is common to many player vs. environment video games. As Sony Santa Monica’s combat designer Denny Yeh has noted about monster design for the God of War reboot series, designing an enemy also means designing what it can “make the player do.” If enemy moves are designed as complementary to the ones of the protagonist, then the hero is inevitably tainted with the monstrosity of their foes.

At the end of Shadow of the Colossus, Wander himself turns into a gigantic smoke monster and attempts to kill the men who came to seal the power he has unleashed. The closing cinematic suggests that he was reborn but that his sins were not forgotten. His story is a warning not only against breaching the boundaries of life and death, but also against anthropocentric hubris that has caused so much damage in the world we live in.