The Evolutionary Case for Sex

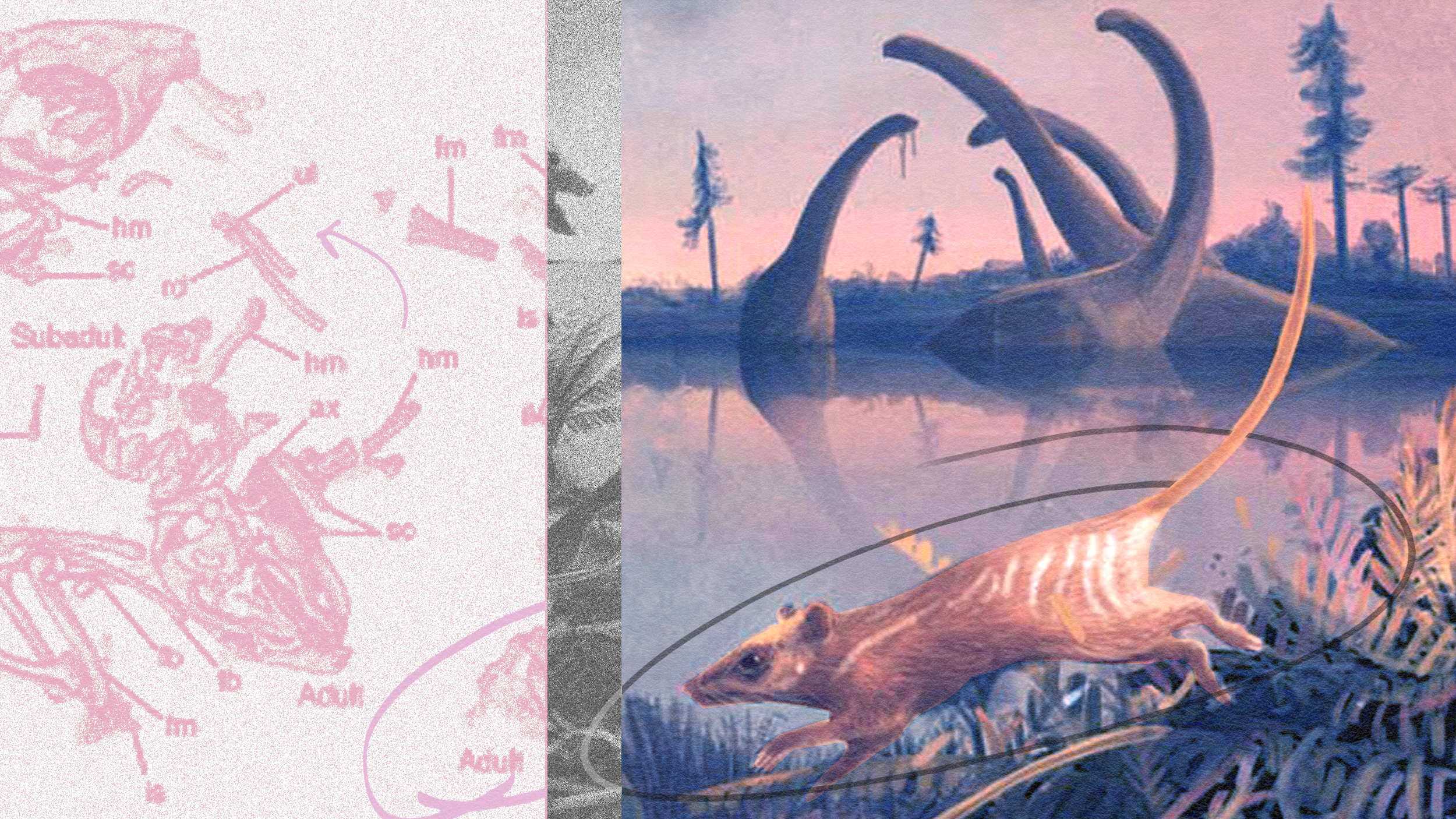

Often when we hear people arguing about the point of sex, it is defenders of sex education who fight moralist crusaders that want to save it for marriage and procreation. But in the world of evolutionary biologists, who see everything through the lens of natural selection, there is an entirely different debate about the point of sex. According to several new biological studies, it’s simply another tool in the evolutionary fight against parasites.

Here’s why the sex question has been baffling to biologists: lots of organisms reproduce asexually, simply by popping off a clone of themselves. It’s simple, it doesn’t require you to expend the energy involved in finding and wooing a mate, and it means that you get to pass on all your genes instead of only half. In addition, asexual reproduction allows a population to expand much faster. Think of it this way—if you want two offspring and so does you mate, then you make them together. But if you came from a species that reproduced asexually, you’d both have two offspring yourselves, and the total community population would double. Scientists call this the two-fold cost of sex.

You’d expect, then, that because organisms are interested in passing on as much of their genetics with the least possible energy expenditure, life would favor asexual reproduction. Yet here we are in a world filled with life forms that reproduce with sex, and enjoy it very much, thank you. There have been competing hypotheses to answer this question, but the one involving defense against parasites has been picking up steam.

The argument, put simply, is that sex overcomes any disadvantages with one great strength: it shuffles the genetic deck. Because offspring are a hybrid of mom and dad rather than a near-exact clone of a single parent, sexually-reproducing communities have more genetic diversity than asexually-reproducing ones, and that makes them a harder target for wily parasites.

A team of biologists just went down to New Zealand to study a kind of snail that does both—some pockets of the snail reproduce one way, some the other. Sure enough, they found that the sexual populations were more resistant to parasite attacks than their asexual cousins.

And it’s not just for animals: a separate study on primrose plants, which can reproduce either way, found that sexual ones could fight off herbivore insects better than asexual ones.

So is sex just a scheme to stay a step ahead of parasites and predators? Perhaps. But the nice thing about self-awareness is that we don’t have to be bound by such strict definitions—there may be one true answer to the question of how and why sex started, but what it means now is up to us.