Ease productivity overload with “niksen,” the Dutch art of doing nothing

- Modern life offers an endless gauntlet of work, worries, and stimulation.

- Niksen is the practice of setting aside time to do absolutely nothing.

- Research shows that rest and relaxation are associated with improved focus, reduced stress, and bolstered creativity.

When was the last time you did nothing? By that, I don’t mean scrolling through social media, watching reruns of Always Sunny, or fretting over the latest office drama. I mean nothingness with no purpose and no goal other than to just enjoy being.

If you’re like most people, you’re likely to have difficulty recalling such a luxurious moment. And even if you could, would you admit it? The more you think about it, the more you realize how incredibly difficult it is not only to find the time for nothing but to own it without embarrassment.

In our work- and improvement-focused culture, doing nothing isn’t the mark of time well-spent. Check the dictionary, and you won’t find a positive-sounding label for a do-nothing. You will, however, uncover an array of words discouraging the very idea with all the disappointment of a priggish grandpa: deadbeat, laggard, lazybones, loafer, slacker, couch potato, and lotus eater.

Little wonder then that we fill our schedules with work, activities, and chores under the pressure to constantly produce — even if such busywork is for the sake of performance.

But we may finally have a word that not only embodies the joys of unoccupied moments, but the benefits it can bring too. It’s niksen, and it’s on loan to us from the Netherlands.

Rebranding niksen

In its native Dutch, niksen means literally “to do nothing.” According to Maartje Williems, the author of The Lost Art of Doing Nothing, the verb is derived from the noun niks (nothing), and it wasn’t coined to be a ringing endorsement. This is evidenced by its lexical cousin niksnut — essentially, a layabout who does nothing and doesn’t contribute to society. (The Netherlands has its share of finger-wagging grandpas, too.)

But in recent years, niksen has undergone a rebranding. In 2017, journalist Gebke Verhoeven published an article titled “Niksen Is the New Mindfulness” in the magazine Gezond Nu (Healthy Now). The article applied the Dutch verb to the benefits of relaxation that psychologists and sociologists were seeing in their research.

As Verhoeven wrote: “We cram our free time so that we don’t have a minute left to just do nothing. Is that bad? Yes, that’s bad. You don’t give your brain space and time to process information and feel what you really need. In short, you lose yourself a bit. High time to elevate idleness to art.”

Your few days together have been spent doing nothing really, which is something, is an intimacy in itself.

Caleb Azumah Nelson

The article inspired other journalists to explore the research under the label of niksen too — among them Olga Mecking, who wrote a popular piece on the subject for The New York Times. As if by providence, many of these articles were published in 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly forced people to consider how to spend their idle time.

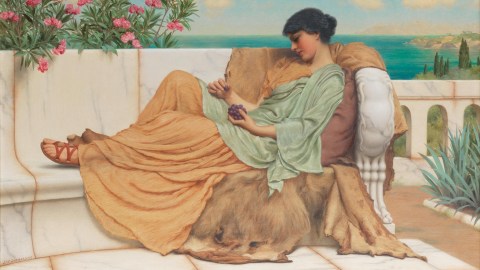

For the record, Dutch isn’t the first language to coin a term for the splendor of laziness. Italian, for example, has the tasty expression la dolce far niente (literally, “sweet doing nothing”). The expression doesn’t get much play today as it sounds a bit dated and cliched to modern speakers. It did, however, serve as the inspiration for several works of art, including a series of oil paintings by Neoclassicist John William Godward.

But it seems niksen — which is, admittedly, more compact — seems to have gained widespread acceptance as the word to represent the concept.

How does one practice niksen?

To niksen, you only need to be idle for a time without trying to be productive or fulfill a purpose. That’s it. It seems about as easy as curling up in your favorite chair. Yet in practice, it’s far more difficult.

Imagine, for example, that you work remotely, and you take a break to clean out the dishwasher. Is that niksen? No. You’re using your time to be productive, and that’s not doing nothing. What about scrolling through your Instagram feed? No, because you’ve used the time to catch up with all the online happenings.

Even if you sit doing nothing, your mind can betray your endeavors. Spending the time planning out an upcoming presentation means you’re still at work. And, despite the title of Verhoeven’s 2017 article, mindfulness isn’t niksen either. Mindfulness has the explicit goal of being fully present in the moment. Meanwhile, niksen’s purpose-free musings are more akin to mindlessness.

It is awfully hard work doing nothing.

Oscar Wilde

So what does count? Staring out the window and watching birds flit around. Enjoying the aroma of your coffee brewing in the morning. Having a pleasant daydream as you listen to music on the couch. Sitting in a cafe and watching the people pass by. It’s any “unguarded moment,” Williems writes, of “having nothing to do and not finding something new to do.”

Beyond that, there are no hard-and-fast rules. Williems recommends the moments be spontaneous, have no time limit, and be in a distraction-free environment. But Carolien Hamming, managing director of CSR Centrum, a stress coaching center, advises you to schedule sessions and use a timer, especially if you’re just starting out. Some even suggest incorporating an easygoing activity that lacks a goal. Think of things like walking, knitting, pen spinning, or brewing a cup of tea.

“Dare to be idle,” Hamming told TIME. “It is all about allowing life to run its course, and to free us from obligations for just a moment.”

The benefits of being a do-nothing

I am unaware of any studies that have specifically looked at niksen as detailed above. The concept is likely too new and amorphous. We’ll have to wait and see. With that said, a lot of research points to the benefits of rest and relaxation, and niksen could offer similar benefits for people who find the practice checks both of those boxes.

One such benefit is improved focus and decision-making. Your frontal lobe — a section of the brain involved in decision-making and self-control — grows fatigued the more cognitive load is put on it. When you rest, your frontal lobe throttles down and lets your default mode network take over. This different brain state reduces the cognitive load so your frontal lobe has more energy when you return to your daily to-dos.

While your brain revives most when you sleep, research shows that resting throughout the day can offer mental boosts. As Emily Maloney wrote about her niksen experience for The Washington Post: “These breaks in my day were most helpful when I was tired and needed a reset, when I was looking for space to be creative, or when I was having trouble focusing on a task I needed to do. Instead of fighting my natural rhythms, I gave in to them.”

Cognitive load can also explain why breaks that include chores, social media scrolling, and the like aren’t as effective. Rather than allowing your frontal lobe to wind down, they thrust a whole new gamut of decisions and self-control challenges at it.

Don’t underestimate the value of doing nothing, of just going along, listening to all the things you can’t hear, and not bothering.

A.A. Milne

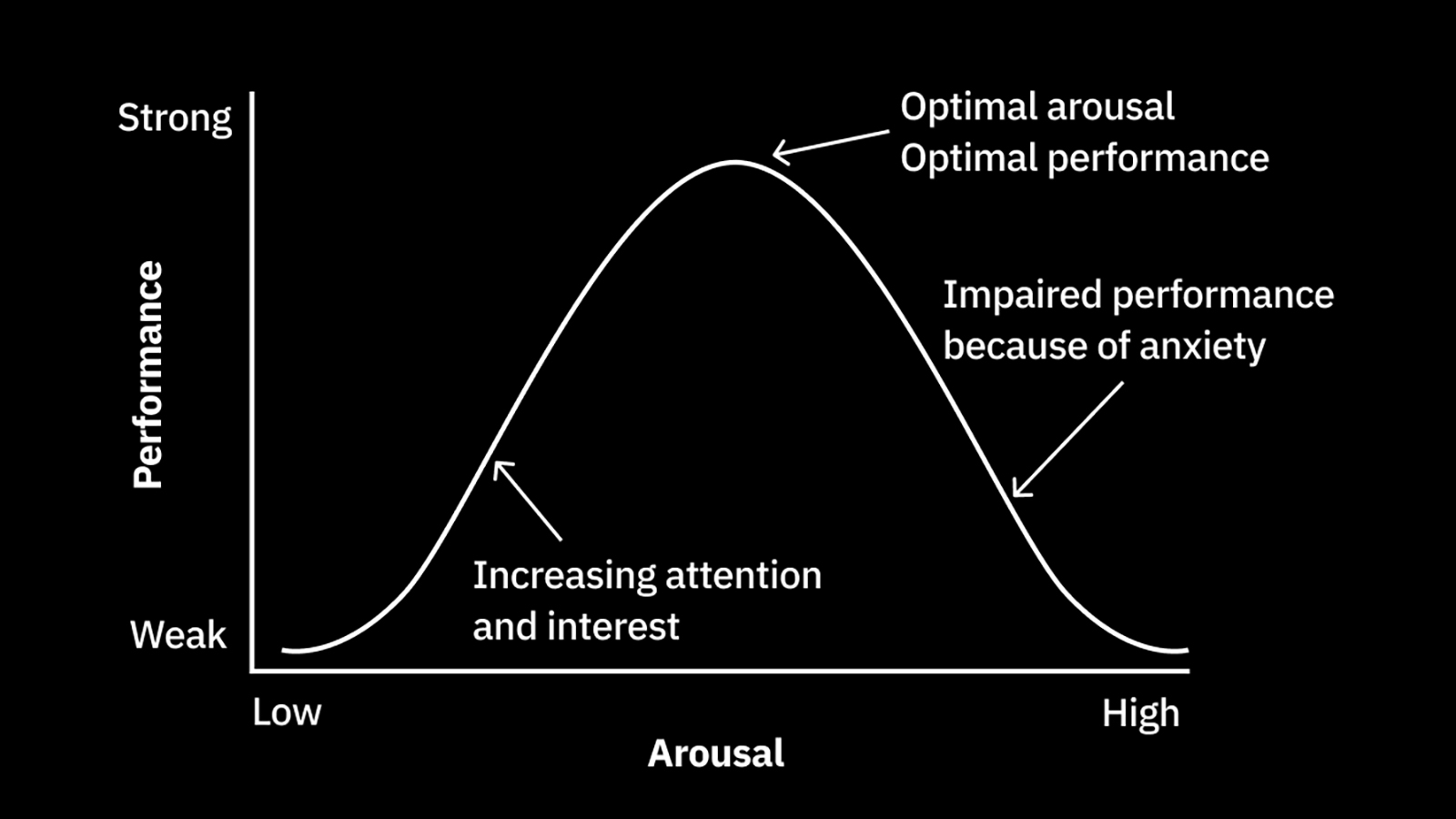

Meaningful breaks have been shown to help reduce stress, too. While some stress can motivate you to accomplish a task or rise to a challenge, too much stress or stress held for too long can harm your performance and productivity. It isn’t great for your health and well-being either.

By building relaxing moments into your days, you can better balance your stress levels by tapping into your “rest-and-digest” response (the counterpart to the more famous “fight-or-flight” response). These breaks can also help you create better boundaries between times of rest and those of intense focus.

“Niksen appeals to a desire for a simpler, more minimal lifestyle,” Mecking writes in her book, Niksen: Embracing the Dutch Art of Doing Nothing. “As you become comfortable with niksen, you will also become more comfortable with refusing to be so busy. Niksen will help you let go of some of that busyness instead of adding to it.”

Finally, creativity and problem-solving can also be boosted by moments of respite. According to Emma Seppälä, associate director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, research shows creative thinking is at its peak when our brains are swimming in slow-moving alpha and delta brain waves. These waves are most prominent when you are at rest, and your default mode network is activated.

“So if you remain focused all the time — constantly doing, doing, doing — you’re not allowing yourself into that mode that will actually lead to the greatest creativity that you have,” Seppälä said in an interview.

Balancing niksen with something

I’ve written previously about how mind-wandering can cause unhappiness, boredom is a warning, and daydreaming can be a cause of distress. That may suggest that shying away from doing nothing is wise in most respects. But it’s worth reiterating that these normal mental happenings only become problematic when they interrupt the moments during which we want to pay attention: work projects we find meaningful, evenings out with family, and hobbies that bring joy to our lives.

How beautiful it is to get up and go out and do something. We are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you any different.

Kurt Vonnegut

It’s about balance. We need moments to breathe and recover, so when we return to the active part of our lives, we’re fully engaged and appreciative. At the same time, our active lives should allow us to appreciate the joys of just being without a sense of guilt.

As Rutt Veenhoven, a sociologist at Erasmus University Rotterdam, told Vogue: “The pace of life today is fast because there is much to enjoy. This is one of the reasons for the high level of happiness in modern society. Activity is a powerful driver of happiness, both because it keeps us fit and because active people build up more resources in work and relationships.”

He added: “Niksen provides a relief for people who feel overwhelmed by the pace. It is also an attractive idea for those who are not overwhelmed but still feel the pressure, too.”

Does niksen work? For some people, yes. For others, probably not. It all depends on how we as individuals can best find that relief from the constant hustle of modern life. But make no mistake: We all need that relief.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.