Women face 5 biases in STEM. Here’s how to bridge the gender gap.

- Women make up about a quarter of all STEM professionals.

- They report facing the prove-it-again bias and others much more than their white male colleagues.

- Author Ruchika Tulshyan recommends six interpersonal habits to help people and workplaces bridge the gender gap.

After decades of struggle, campaigning, and accomplishment, women have made hard-won gains in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

In the U.S. today, women earn about half of the degrees awarded in science and engineering. They make up a majority of psychologists and social scientists and work nearly half the jobs in math and the life and physical sciences. All the more incredible is that these groundswell shifts have taken place within some professionals’ lifetimes.

However, factoring in the entire STEM spectrum, women only represent about 27% of the workforce. This disparity results from women’s lack of comparable gains in fields such as engineering and computer technology. The vast majority of STEM jobs reside in these fields, yet women remain a minority. For example, they make up 15% of all U.S. engineers.

What accounts for this persistent gender gap? As with any such phenomena, there is likely no one answer but a complex interplay of social, cultural, professional, and, yes, biological realities. According to Joan C. Williams, a professor of law at the University of California-Hastings and a founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law, one of these realities is the common patterns of gender bias faced by women in these and many other professional fields.

The 4 patterns of gender bias

Williams has surveyed and interviewed thousands of STEM workers. From those interviews, she’s developed a framework of the four major patterns of gender bias faced by professional women.

The first pattern is the prove-it-again bias. Women report that they must continuously re-establish their skills, strengths, and credentials or risk having their expertise discounted. By Williams’s estimate, women must provide twice as much evidence of their competence to be seen as equally capable to their male colleagues.

In her book, Inclusion on Purpose, inclusion strategist Ruchika Tulshyan notes the pervasiveness of this bias in women’s experiences at work, especially for women of color:

“Over the years, constantly facing prove-it-again bias becomes soul crushing for women of color. Like being asked to reestablish their credentials in meetings, or having ideas ignored in meetings until they’re repeated by white men or women, or being denied pro- motion or tenure despite being overqualified for the opportunity. Every woman of color I spoke to for this book could name multiple instances of facing these biases.“

Next is the tightrope bias. It describes the balancing act women face between being viewed as too feminine (likable but not respected) or too masculine (respected but not likable). The former may lead to them taking on excessive “office housework,” whereas the latter could lead them to be evaluated as “not a team player.”

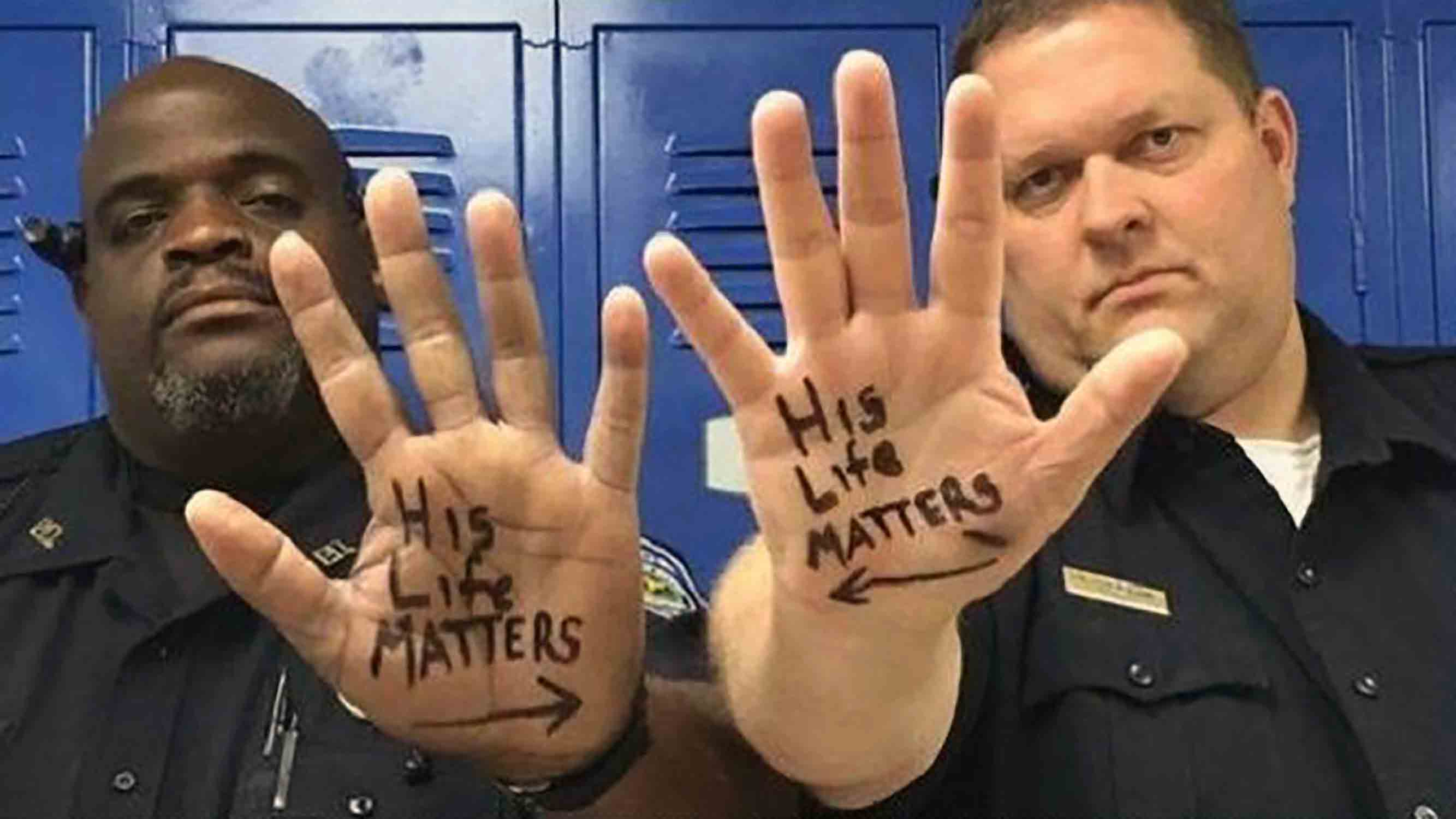

Just because it isn’t your experience, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist.

– Ruchika Tulshyan

The tug-of-war bias describes the conflict between women as they compete for “the women’s spot.” Williams notes that women who encountered discrimination earlier in their career may internalize those stereotypes and place similar burdens on younger professionals — the so-called “queen bee” phenomenon.

And the final pattern is the maternal wall. After women become parents, they find their dedication questioned, their opportunities limited, and as a result, their confidence shattered.Williams sometimes includes a fifth pattern to her framework: isolation. This pattern, she writes, mainly harms Black and Hispanic women and describes the experience of feeling that social engagement or discussing personal matters will negatively affect others’ perception of them.

The E is not for equal experience

In a survey conducted by the Society of Women Engineers, in partnership with the Center for WorkLife Law, Williams and her co-authors asked more than 3,000 engineers with at least two years of experience in the field about their encounters with the four patterns. Their findings showed that female engineers report experiencing confronting these biases more often than White men.

For example, 61% of women say they have to repeatedly prove themselves compared to 35% of White men. Regarding the tightrope bias, women were less likely to believe they could behave assertively but more likely to feel pressured to do office housework than White men (51% vs. 67% and 55% vs. 26%, respectively). And “nearly 80% of men said having children did not change their colleagues’ perceptions of their work commitment or competence; only 55% of women did.”

The only bias that did not present a large gender gap was the tug-of-war bias. Only a fifth of the women sampled agreed with the statement, “I am regularly competing with my female colleagues for the women’s slot.” Though interestingly, men were less likely than women engineers to agree with the statement, “Some women engineers just do not understand the level of commitment it takes to be a successful engineer” (11% vs. 24%).

It’s not just STEM

None of this is to say that STEM in general, or engineering in particular, is atypically toxic. Women outside of STEM report similar experiences.

A survey conducted by the American Bar Association’s Commission on Women in the Profession — also led by Williams — found similar gender disparities among lawyers despite women being far better represented in that field. (More than a third of lawyers in the U.S. are women.)

And while the annual Women in the Workplace report doesn’t ask about the four patterns directly, it does contain questions that overlap with William’s framework. In the 2021 report, mothers were more likely than fathers to report feeling burnout, being judged, and being viewed as less committed. The 2019 report found that twice as many women as men felt the need to provide more evidence of their competence.

A lot of what the BRIDGE framework does is it invites more of us to reflect on the perspectives that perhaps we’ve held, especially around communities that are different than our own.

– Ruchika Tulshyan

With all this said, the research isn’t entirely disheartening. When the Society of Women Engineers survey asked about fair treatment at work, the majority of both men and women engineers agreed that they received honest feedback, their performance evaluations were fair, and they had been provided the advancement opportunities they deserved. The reported gender difference for these experiences was less than 10%. That’s still several percentage points too many, but it shows incredible progress from the Mad Men-era of office politics.

It’s also worth reiterating that Williams’s framework is only one piece of a growing — and sometimes confounding — body of research on gender bias in the workplace.

Surveys conducted in traditionally women-dominated professions, such as nursing, have shown gender biases and stereotypes that disfavor men. Similarly, men face bias at work over their roles as fathers, but instead of having their dedication questioned, they are viewed as weak and lacking in conviction. And one more complexity for the road: When research looks beyond the U.S., it finds that women in more gender-equal societies are less likely to go into a STEM field than women living in less equal societies.

Bridging the gender gap

Discovering ways to reduce how people experience biases helps create a great place to work for everyone. In her book, Tulshyan recommends six steps we can all take to help overcome the gender gap. She lays out these steps in the acronym BRIDGE.

Be okay with being uncomfortable

Tulshyan points out that a growth mindset requires us to explore uncomfortable places. “We must push past feelings of uncertainty, fear, discomfort, and frustration to create equity and justice everywhere, but especially in our workplaces,” she writes.

Reflect on what you don’t know

We all have a limited perspective by dint of being stuck with our own minds and experiences. As such, we should take the time to consider our blind spots.

Talk with people from other communities and perspectives. Read books that don’t confirm your preconceived notions. And try “steelmanning” rather than “straw-manning” arguments you disagree with when in a debate.

Invite Feedback

Another way to broaden our perspective is to simply ask questions. Feedback provides a social and connective means to cultivate a growth mindset and practice inclusion in action.

Defensiveness doesn’t help

Anyone can become defensive at the prospect that they are ignorant of something so plain to others. “Just because it isn’t your experience, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist.”

Grow from mistakes

We won’t always get it right. We’ll make mistakes — some accidentally, some from carelessness, and others from ignorance. But each mistake provides an opportunity to grow if you take the time to learn the lesson.

Expect that change takes time

Change takes time, and it’s easy to become frustrated when you don’t recognize the gains in the present. Remember that small, gradual changes combine to create powerful effects in time.

As Tulshyan told us in an interview: “A lot of what the BRIDGE framework does is it invites more of us to reflect on the perspectives that perhaps we’ve held, especially around communities that are different than our own.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Ruchika Tulshyan’s full class for your organization, request a demo.