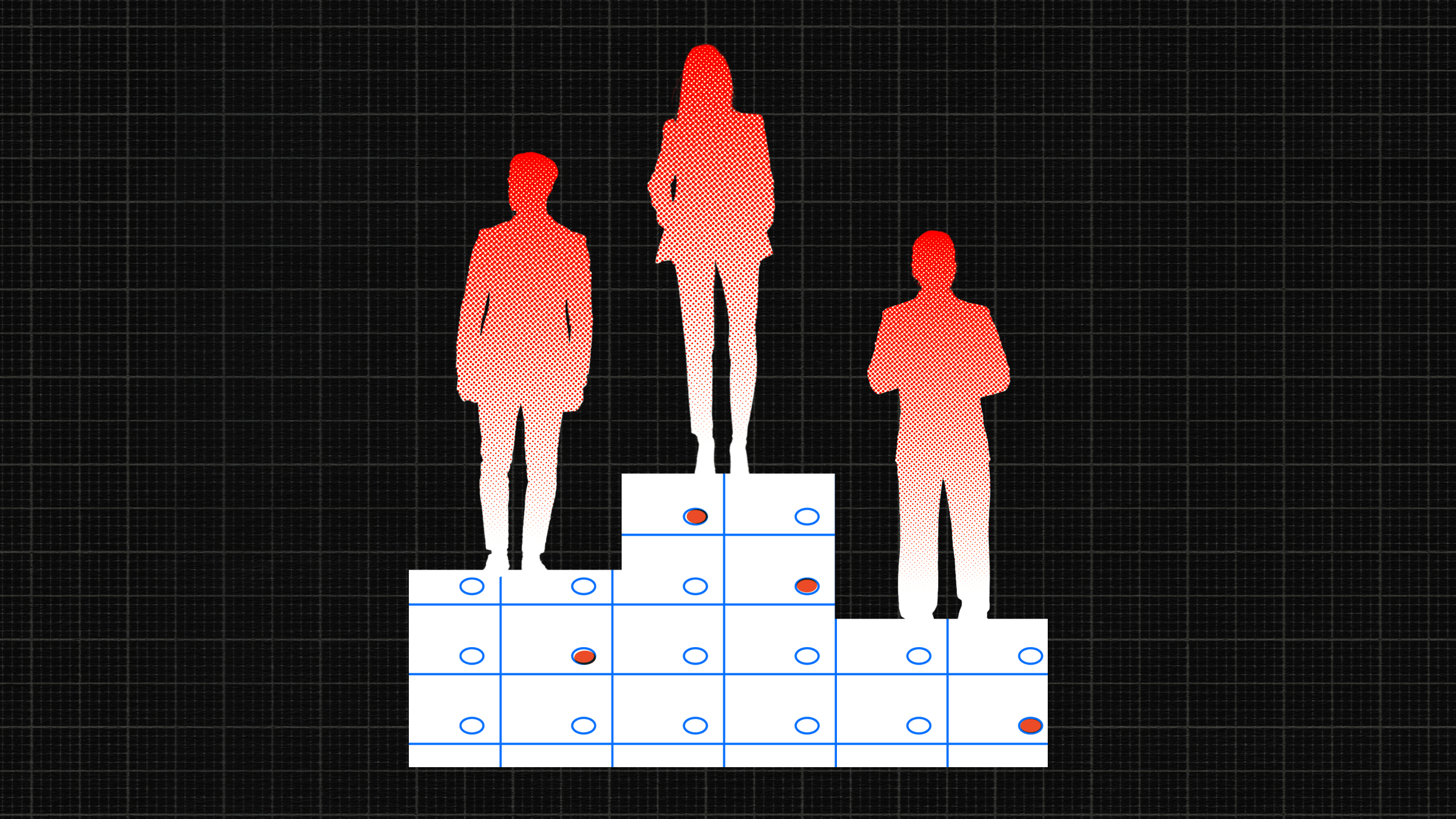

Horse Race Coverage & the Political Spectacle

At Time magazine, a focus on who will break out of the pack?!

As the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary approaches, it’s all horse race all the time in the news media with an almost exclusive focus on “insider” coverage of campaign strategy and a fascination with who’s ahead and who’s behind in the polls. Lost in the media spectacle is any careful coverage of issues and policy proposals, or serious discussion of candidate background. In fact, it seems there’s never been a time in 2007 where issues have taken primacy over the sports game of political coverage.

Consider that an analysis by Pew and Harvard University of the first five months of coverage in 2007 finds that 63% of the campaign stories focused on political and tactical aspects compared to just 17% that focused on the personal backgrounds of the candidates, 15% that focused on the candidates’ ideas and policy proposals and just 1% of stories that examined the candidates’ records or past public performance.

I was asked to contribute an overview on horse race journalism to the forthcoming Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. Below I have posted a first draft of the overview, at roughly 1800 words it provides a good backgrounder on the nature and impacts of horse race journalism, though I strongly recommend checking out the sources cited.

Horse Race Journalism

Matthew C. Nisbet, Ph.D.

In contemporary political reporting, a focus on elections and policy debates as “a game” among competing candidates and elites has come to dominate virtually every aspect of coverage. Rather than foregrounding issue positions, candidate qualifications, or the context behind a range of policy proposals, journalists instead tend to cast these features of the political terrain as secondary to a focus on who’s ahead and who’s behind in winning the campaign or policy battle, the generals and lieutenants involved, and the shifting strategies and tactics employed. This dominant narrative is referred to commonly as “horse race journalism,” (Patterson, 1977), the “game schema,” (Patterson, 1993), or the “strategy frame” (Capella and Jamieson, 1997.)

Horse race journalism focuses almost exclusively on which candidates or players are most adept at gaining power while also undermining the political chances of opponents. “Horse race” is an apt metaphor as much of contemporary political reporting translates easily into the conventions of sports coverage, with a focus on competing political gladiators who survive to campaign another day or who are the first to cross the finish line. Polling and public opinion surveys are a central feature of this political spectacle. In fact they supply the “objective” data for reporters to define who is winning while offering a news peg for offering attributions about the reasons for political success or failure.

The Rise of Horse Race Journalism

Over the past forty years, the rise in horse race journalism has been called by Patterson (1993) the “quiet revolution” in U.S. election reporting. His now classic analysis finds that coverage focusing on the “game schema” that frames elections in terms of strategy and political success rose from 45% of stories sampled in 1960 to more than 80% of stories in 1992. In comparison, coverage focusing on “policy schema,” framing elections in terms of policy and leadership, dropped from 50% of coverage in 1960 to just 10% of coverage analyzed in 1992.

Other analyses confirm the contemporary dominance of the horse race interpretation in election coverage. In one study of the 2000 U.S. presidential campaign, strategy coverage accounted for more than 70% of the TV stories at the major news networks (Farnsworth and Lichter, 2003). The most recent available analysis–tracking the first five months of 2007 presidential primary coverage–found that horse race reporting accounted for 63% of print and TV stories analyzed compared to just 15% of coverage that focused on ideas and policy proposals and just 1% of stories that focused on the track records or past public performance of candidates (Pew 2007).

In the U.S. context not only has horse race and strategy come to define elections, the convention also increasingly characterizes coverage of what were originally considered complex and technical policy debates. First observed by Capella and Jamieson (1997) in their analysis of the early 1990s debate over health care reform, when coverage of policy debates have shifted from specialty beats to the political pages, the strategy frame has been tracked as the dominant narrative in reporting of issues as diverse as stem cell research, climate change, food biotechnology, the Human Genome Project, and the teaching of evolution in schools (Nisbet and Huge, 2006).

Reasons for the “Quiet Revolution” in Political Journalism

Horse race journalism is fueled in part by industry trends and organizational imperatives. In a hyper-competitive news environment with a 24 hour news cycle and tight budgets, reporting the complexity of elections and policy debates in terms of the strategic game is simply easier, more efficient, and considered better business practice.

Public opinion surveys are a competitive advantage in the news marketplace; they are even an important part of media organization branding and marketing. Perhaps more importantly, polls help fill the demand for “anything new” in a day long coverage cycle while also fitting with trends towards “second hand” rather than primary reporting (Rosenstiel, 2005).

The growth in political polling has helped fuel the rise in horse race coverage. For example, in analyzing trial heat polls between the two major party nominees, Traugott (2005) reports a 900% increase in such polls between 1984 and 2000. In 2004, the total number of trial heat polls remained equivalent to the previous presidential campaign, but there was more of a mix of different types of polls, as several organizations focused specifically on anticipated battleground states.

Rosenstiel (2005) observes that the increase use of tracking polls likely magnifies horse race coverage. In these polls samples of 150-200 respondents are combined across two to three nights allowing journalists to rely on an almost daily diet of “up and down” indicators.

In combination with economic imperatives and the increased availability of polling, horse race coverage also resonates strongly with the informal rules of political reporting. American journalists pay heavy attention to scandals, corruption, or false and deceptive claims but because of their preferred objectivity norm, they typically shy away in coverage from actively assessing whether one side in an election or policy debate has the better set of candidates, ideas, or proposed solutions. With a preference for partisan neutrality, it is much easier for journalists to default to the strategic game interpretation. Issue positions and policy debates are part of this coverage but very much secondary to a dominant narrative of politics that turns on conflict, advancement, and personal ambition (Patterson, 1993; 2005).

Rosenstiel (2005) connects the objectivity norm to the new “synthetic journalism” that further emphasizes poll driven horse race coverage. In a hyper-competitive 24 hour news cycle there is increasing demand for journalists to try to synthesize into their own coverage what has already been reported by other news organizations. This might include new insider strategy, the latest negative attack, or a perceived embarrassing gaffe or mistake. The need to synthesize critical or damaging information runs up against the preferred norm of objectivity while also providing potential fodder for claims of liberal bias.

Polls, however, help insulate journalists from such claims since they provide the “objective” organizing device by which to comment and analyze news that is being reported by other outlets. For example, if a new survey indicates that a candidate is slipping in public popularity, the reporting of the poll’s results provides the subsequent opening for journalists to then attribute the opinion shift to a recent negative ad, allegation, or political slip up. As news organizations rely more and more on public opinion surveys and tracking polls as branding devices and news pegs, a focus on horse race coverage and synthetic journalism is only likely to be magnified.

Frankovic (2005) observes a dramatic rise not just in the reporting of specific poll results, but importantly, in terms of general rhetorical references to “polls say” or “polls show,” with close to 9,000 such general mentions at newspapers in 2004 compared to roughly 3,000 such mentions in 1992. This reliance on the authority of polls adds perceived precision and objectivity to journalists’ coverage. According to Frankovic, this rhetorical innovation in reporting allows journalists to make independent attributions about candidate success or failure without relying on the consensus of experts. Moreover, she argues that the heightened emphasis on “the polls” alters the criteria by which audiences think about the candidates, shifting from a focus on issue positions and qualifications to that of “electability.”

Of course, an accent on strategy, ambition, poll position, and insider intrigue is not the only way that political reporters can translate an election campaign or policy debate for audiences. Journalists, for example, could alternatively emphasize issue positions; the choice between distinct sets of ideas and ideologies; the context for policy proposals, or the credentials and governing record of candidates and parties (Kerbel, Apee, and Ross, 2000). Yet in comparison to the horse race, the storytelling potential of each of these alternative ways of defining what’s newsworthy in politics is perceived as more limited. In fact, according to the norms that dominate most political news beats, once the issue positions, credentials, background, or track record of a candidate is first covered, they are quickly considered “old news” (Patterson, 1993).

Reasons for Concern about Horse Race Journalism

Scholars have raised multiple concerns about the impacts of horse race journalism. Patterson (1993; 2005) and others fear that the focus on the game over substance undermines the ability of citizens to learn from coverage and to reach informed decisions in elections or about policy debates. Capella and Jamieson (1997) argue that the strategy frame portrays candidates and elected officials as self-interested and poll driven opportunists, a portrayal that they show promotes cynicism and distrust among audiences. Farnsworth and Licther (2006) go so far as to suggest that horse race coverage in the primary elections results in a self-reinforcing bandwagon effect with positive horse race coverage improving a candidate’s standing in subsequent polls and negative horse-race coverage hurting a candidate’s poll standings. Their observation fits with what many political commentators and candidates complain about, that over-reliance on polling narrows news attention and emphasis to just two to three candidates while over-emphasizing perceived electability as a criteria for voters. In this sense, horse race coverage unduly promotes the media as a central institution in deciding electoral outcomes.

In terms of horse race coverage of policy debates, other than failing to provide context and background for audiences, Nisbet and Huge (2006) argue that the strategy frame’s preferred “he said, she said” style leads to a false balance in the treatment of technical issues such as climate change or the teaching evolution, issues where there is clear expert consensus. Polling experts offer other reservations. For example, Frankovic (2005) and others warn that over-reliance on horse race journalism and polling potentially undermines public trust in the accuracy and validity of polling.

References

Capella, J. N & Jamieson, K.H. (1997). Spiral of Cynicism: The Press and the Public Good. New York: Oxford University Press.

Farnsworth, S.J. and Lichter, S.R. (2003). The Nightly News Nightmare: Network Television’s Coverage of US Presidential Elections, 1988-2000. Rowman & Littlefield.

Farnsworth, S.J. and Lichter, S.R. (2006). The 2004 New Hampshire Democratic Primary and Network News. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11, 1, 53-63.

Frankovic, K. A. (2005). Reporting “the polls” in 2004. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69, 682-697.

Nisbet, M.C. & Huge, M (2006). Attention cycles and frames in the plant biotechnology debate: Managing power and participation through the press/policy connection. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11, 2, 3-40.

Patterson, T. E. (1977). The 1976 horserace. The Wilson Quarterly 1: 73-79.

Patterson, T.E. (1993). Out of Order. New York: Knopf.

Patterson, T.E. (2005). Of Polls, Mountains: U.S. Journalists and Their Use of Election Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 69, 5, 716-724.

Pew Project for Excellence in Journalism (2007, Oct. 29). The Invisible Primary. Press Release and Report.

Rosenstiel, T. (2005). Political Polling and the New Media Culture: A Case of More Being Less. Public Opinion Quarterly 69, 698-715.

Traugott, M. (2005). The Accuracy of the National Preelection Polls in the 2004 Presidential Election. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 5, 642-654.