Amazon’s “economic flywheel” built Seattle. Can your city build one?

- In his new book, Flywheels: How Cities Are Creating Their Own Futures, businessman and author Tom Alberg explores how cities can create conditions that foster entrepreneurialism and economic success.

- This excerpt overviews the concept of flywheels, a term that refers to a suite of conditions and strategies that can spark exponential growth for businesses and cities.

- Alberg uses the concept of flywheels to explain how Seattle rapidly evolved into one of the world’s leading tech hubs.

Adapted from Flywheels: How Cities Are Creating Their Own Futures by Tom Alberg published by Columbia Business School Publishing. Copyright (c) 2021 Tom Alberg. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Among dozens of cities that aspired to be one of the top tech hubs, how did Seattle become one of the two leading centers of technological invention in the world? Why did Jeff Bezos decide to base his internet bookstore here, rather than in Silicon Valley or staying in New York City? Why did home-grown entrepreneurs like Craig McCaw and Bill Gates set their roots down here? Even before them, the companies that gave us the first commercially successful ultrasound imagers, heart defibrillators, and barcode readers sprang up in Seattle.

Why not Minneapolis, Memphis, or Minsk? Why does Seattle continue to be a place that nurtures the development of breakthrough technologies? I’ve spent a long time thinking about this, working with tech companies of all sizes and quizzing colleagues.

All roads lead back to our economic flywheel.

Strictly speaking, a flywheel is a mechanical device, a wheel to which force is applied, creating a rotation that releases energy. Without additional force to turn it, friction will gradually slow the wheel to a halt. But if sufficient new force is applied, the wheel spins faster and faster, creating still more energy that keeps it spinning. Flywheels have been around for at least ten thousand years — potter’s wheels are flywheels. James Watt used a flywheel in his eighteenth-century steam engine that powered the Industrial Revolution.

Writers, too, have found inspiration in the flywheel. Poetry magazine uses its mechanism as a metaphor for the way “energy, movement and potential” generate new ideas. And in her book The Writing Life, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annie Dillard advises writers everywhere: “Get to work. Your work is to keep cranking the flywheel that turns the gears that spin the belt in the engine of belief that keeps you and your desk in midair.”

I was first introduced to the notion of a flywheel as an engine for growing a business at a meeting of Amazon’s board of directors in the fall of 2001. We were in the midst of the dot-com bust, and the company was losing lots of money. Jeff Bezos had assembled his S-team of ten senior executives and board of directors to hear from the management consultant Jim Collins, author of the bestselling book Good to Great (2001). Collins talked about the concept of a business-centric flywheel, which he explained as the effect of numerous small initiatives acting upon each other. Like compound interest, he said, the growth would be slow at first but gain momentum over time.

The economy was highly stressed. The NASDAQ had peaked in March 2000, and now, with the dot-com bubble burst, a recession had set in. Financial markets that had been wildly positive about internet companies during the late 1990s, showering the sector with venture and public capital, had grown jittery — especially bondholders, and Amazon had raised several billion dollars through bond issues. The company’s stock fell from over $100 a share to $6. In May 1999, Barron’s headlined a front-page story “Amazon.Bomb,” and two years later Washington Post columnist David Streitfeld quoted a financial analyst who said he “expects the Internet retailer to run out of money…later this year.”

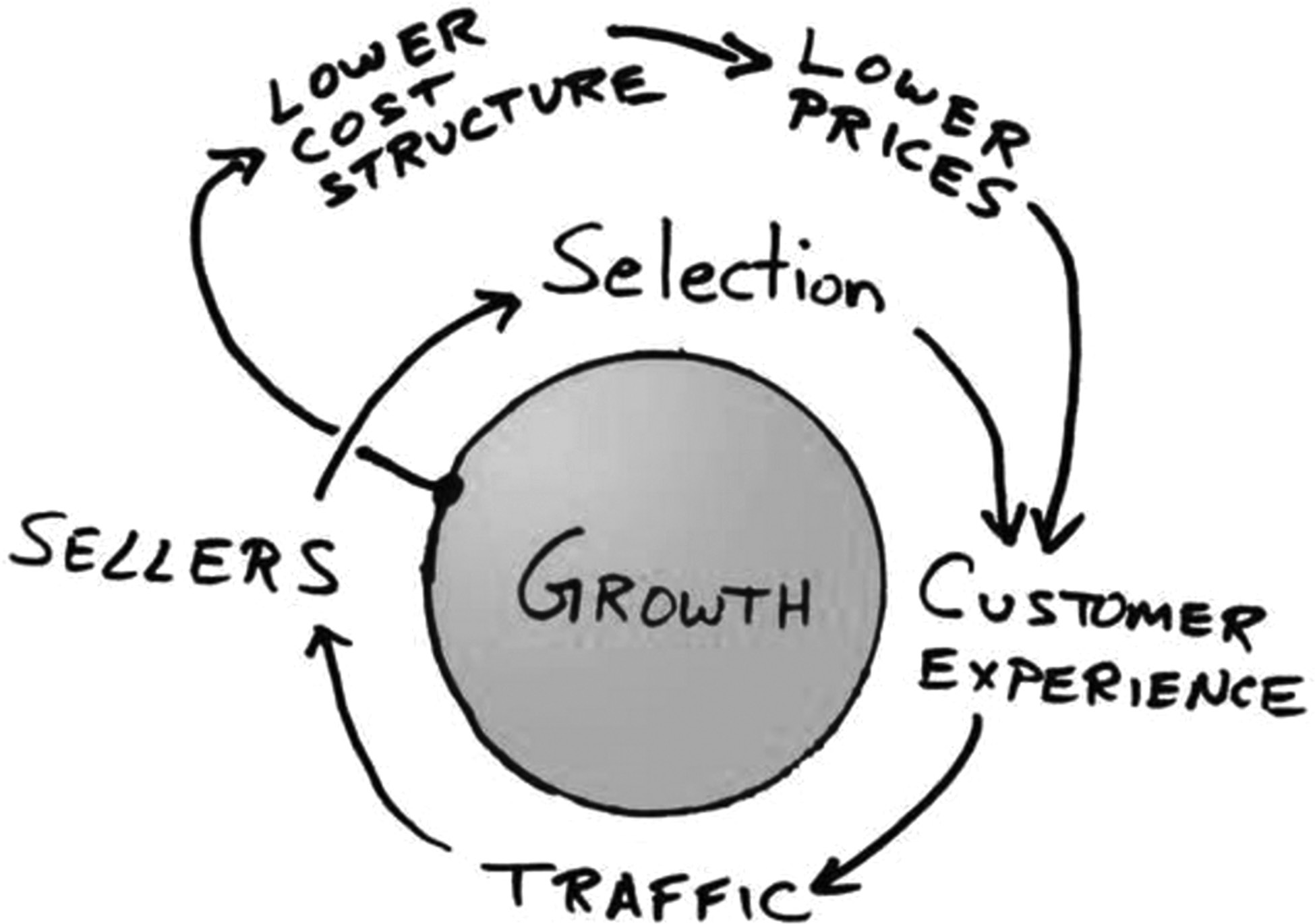

But Bezos was focused on the long term. He’d invited Collins to talk to the board and senior managers about sustainable growth, so Collins drew for us an Amazon-specific flywheel. It showed a virtuous cycle, where low prices brought in customers, and more customers allowed Amazon to add more products for sale, the volume reducing prices further and attracting still more customers in a gradually accelerating flywheel. Bezos liked this concept, and the flywheel — with a few Bezos modifications — became a key part of his guiding philosophy at Amazon. He often uses it in employee meetings and public presentations.

The Amazon flywheel is centered on growth. To generate momentum, it begins by providing buyers a marketplace with great product selection, convenience, and low prices. As consumers are attracted, traffic increases customer experience, which attracts still more customers. As Amazon grows, the flywheel spins faster and faster.

Amazon also uses innovative business processes — such as opening the site to third-party sellers. They appreciate the ease of selling and shipping products through Amazon. The company benefits from a vastly increased inventory, and competition among the sellers lowers prices. The flywheel concept quickly became integrated as a guiding principle at Amazon, which then conceived new flywheels for its Prime and video divisions.

As I began to write this book, in an effort to explain the increasing momentum in Seattle, I thought back to that afternoon with Jeff and the Amazon team. Board members in the room, in addition to Jeff and myself, were venture capitalist John Doerr, then Gates Foundation CEO Patti Stonesifer, and Intuit founder Scott Cook.

At my firm, Madrona Venture, we talk about the three pillars of Seattle’s innovation economy: invention, entrepreneurs, and funding. As I pondered, it became obvious that the most accurate and dynamic way to think about Seattle’s economy is with the concept of a flywheel.

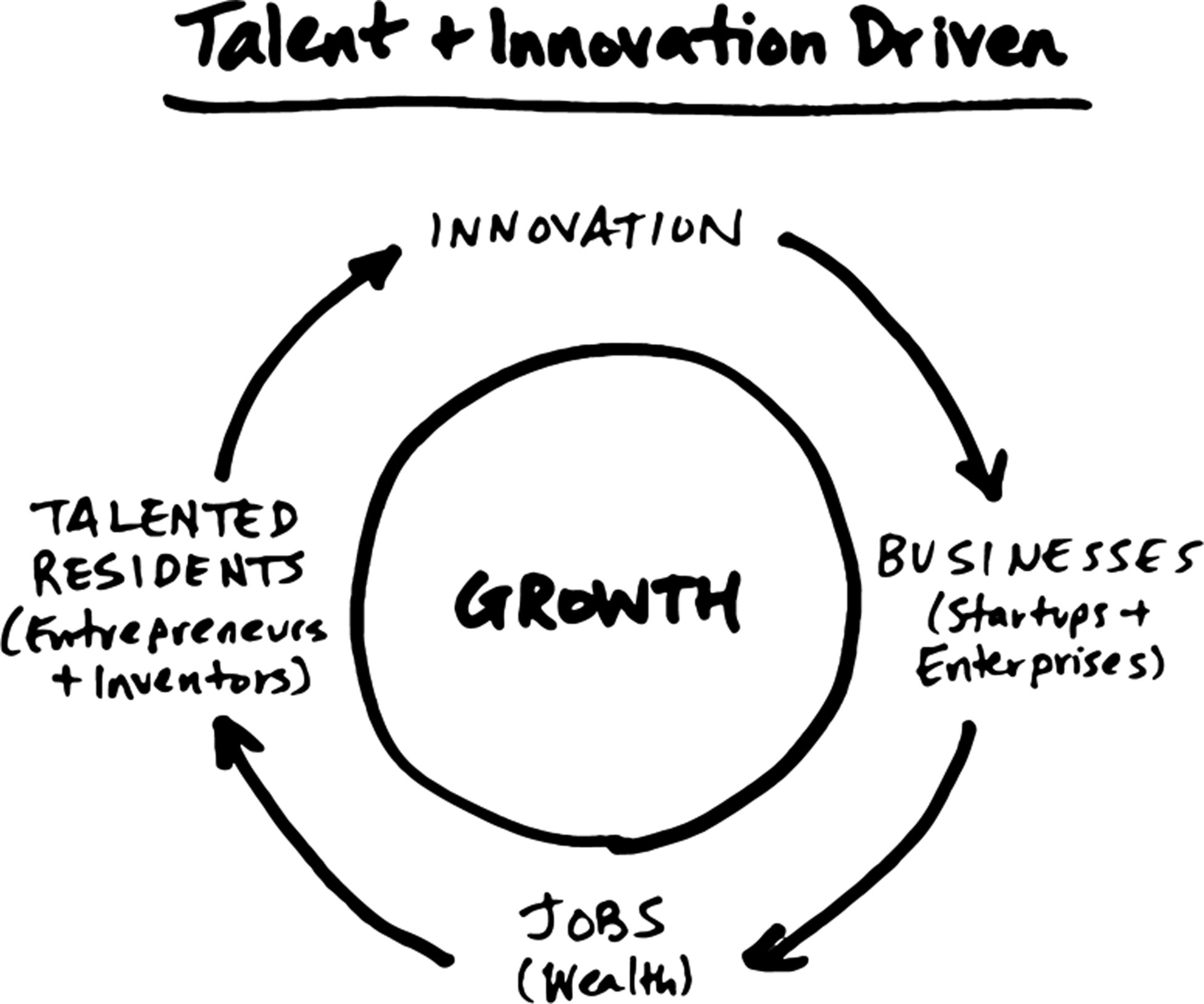

In Seattle’s version, it begins with talented people — entrepreneurs, inventors, and leaders — who create innovations which begets startups. Startups spawn successful companies that then attract talented people who create innovations. Successful companies also generate wealth and jobs, which provides the energy to support the new startups that those creative people inevitably launch. And so the cycle continues. As more talented people move to Seattle, more innovations give rise to new companies, which attract more creative people, and the flywheel accelerates.

This is a useful way to look at the growth of Seattle’s high-tech economy and a model for other cities to emulate when growing their own economies. But how did this flywheel get going before we had lots of creative people, inventions, capital, startups, and successful companies? How did Seattle become a world leader in aviation, software, wireless communication, biotechnology, the cloud, and online retail? How did we become a leading place for innovation of all kinds?

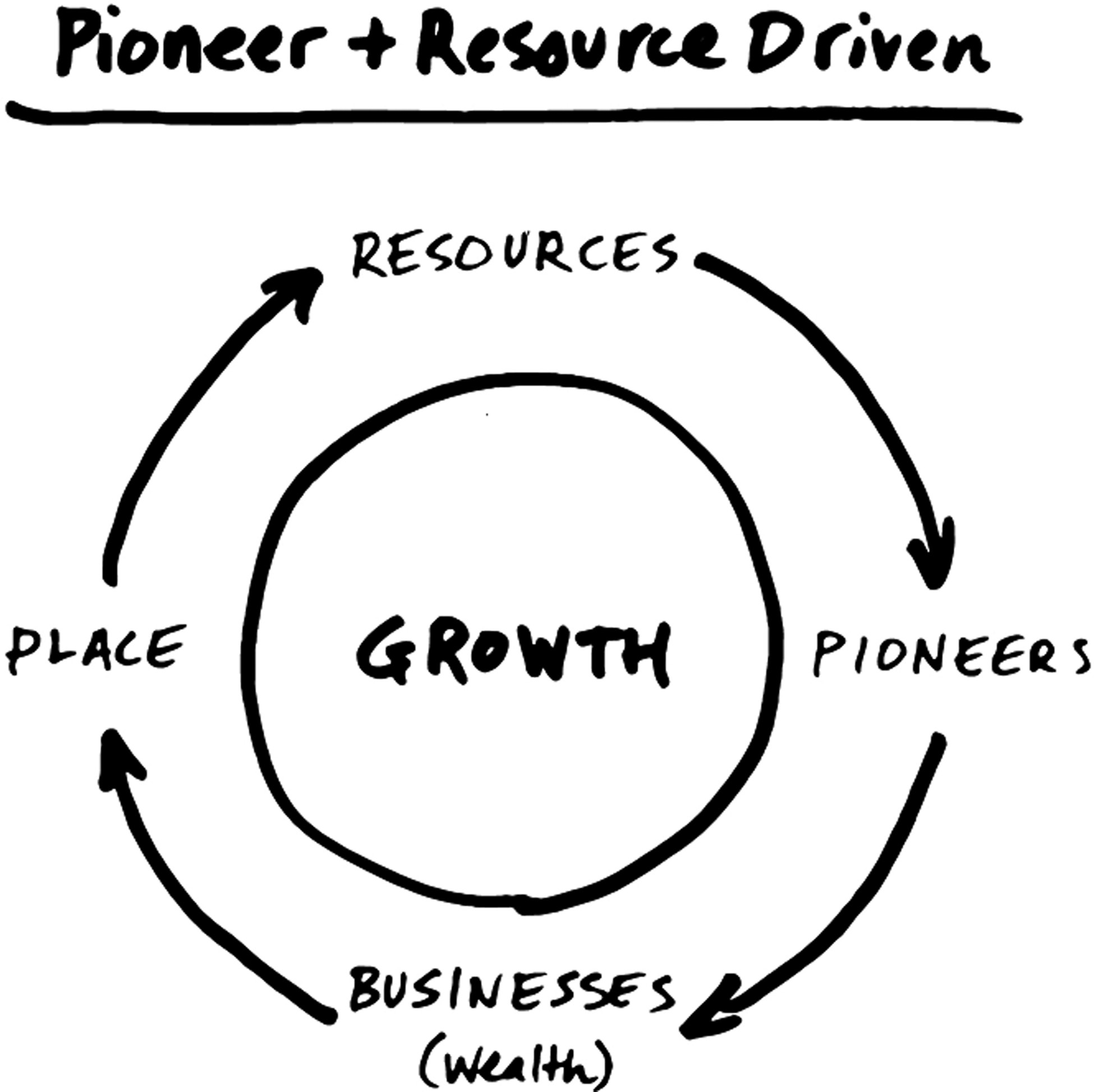

The way I see it, Seattle has had two economic flywheels — one that generated its early growth and one that generates momentum today. What the two have in common is a beautiful setting with plenty of opportunities that attract pioneering, entrepreneurial types, and keep them here.

Seattle’s earliest ingredients for a flywheel are its location and natural resources. You could call that the power of place. In the mid-nineteenth century, it was a remote place, with few residents but plentiful timber and fish. The geographic location of this muddy new town — on the shores of the Pacific, ringed with snow-capped mountains — was itself a magnet for people with dreams. We now refer to it as the Mount Rainier effect, a shorthand for the heart-stopping vistas we use as a recruiting tool even today. But the real draw for Seattle, originally, and still, is opportunity.