The strangest moon in the Solar System

Why Saturn’s Iapetus has three great mysteries… and we’ve only solved one of them.

“The dance between darkness and light will always remain — the stars and the moon will always need the darkness to be seen, the darkness will just not be worth having without the moon and the stars.” –C. JoyBell C.

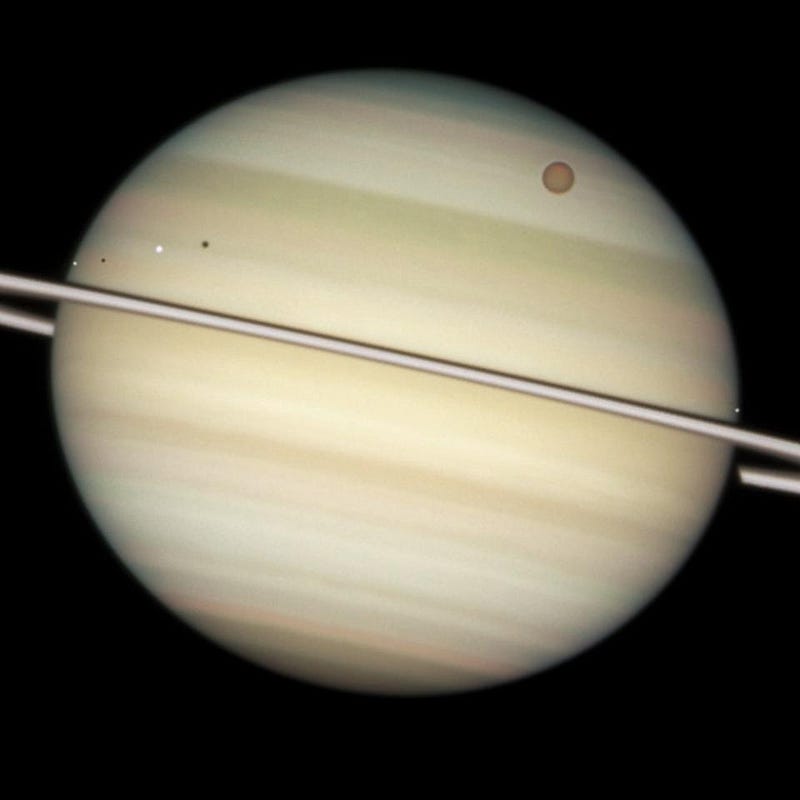

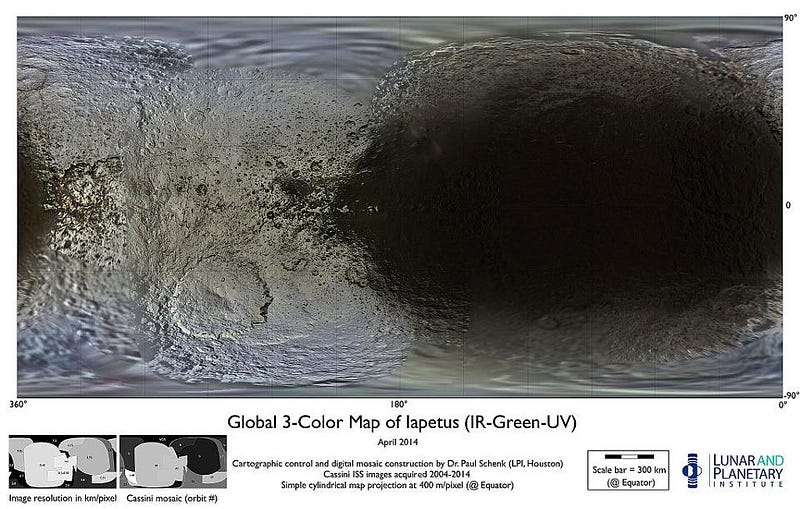

In 1671, Giovanni Cassini gazed through a telescope at Saturn, and discovered a number of incredible wonders: the famed gap in its rings, detailed band structures in its atmosphere, and a number of moons. The second Saturnian moon ever discovered — Iapetus — was immediately caught doing something no other moon had ever done: it was only visible for half of its orbit. The other 50% of the time, Iapetus was completely invisible, unable to be detected by any means, yet seemed to obey the normal gravitational laws throughout. After more than three decades of improvements to the telescope, Cassini was finally able to find this moon on both the western and eastern sides in 1705, but found that it appeared more than six times fainter on the eastern side.

Cassini developed a theory about this moon, now known as Iapetus. He contended that first off, Iapetus must be two-toned, with one side significantly lighter and brighter than the other, darker side, and that secondly, it must be tidally locked to Saturn, so that the same side always faces it. Put this together and the “leading edge” of Iapetus would have to be significantly fainter and darker than the trailing edge. It was an interesting idea, but there was no way to test it.

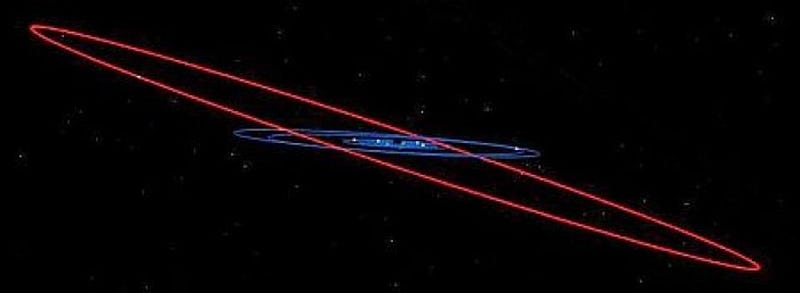

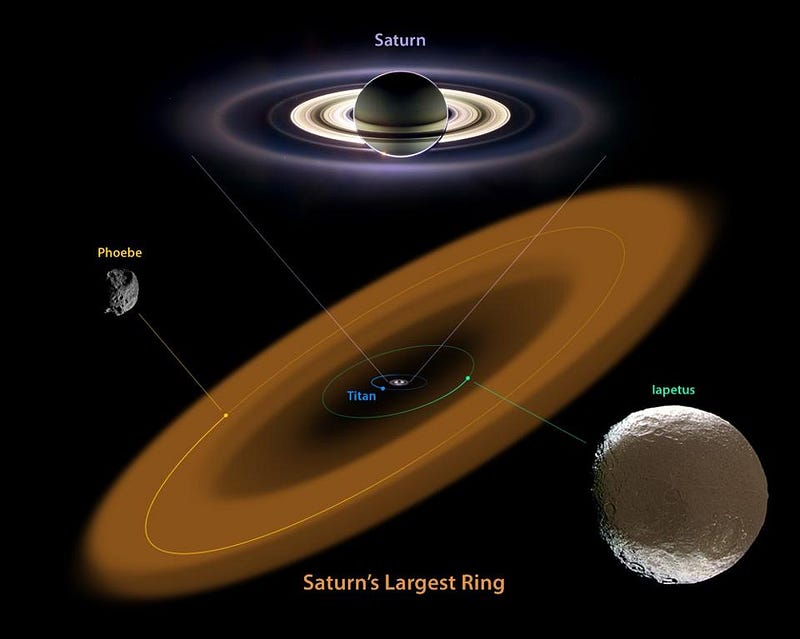

That coloration difference isn’t the only thing that makes Iapetus remarkable, either, or unique among moons. You see, all of Saturn’s major moons orbit in the same plane as its rings: all but Iapetus, which is significantly tilted. And no one knows why; no other large moon in the Solar System that formed along with its parent planet has such a tilt, and yet Iapetus does.

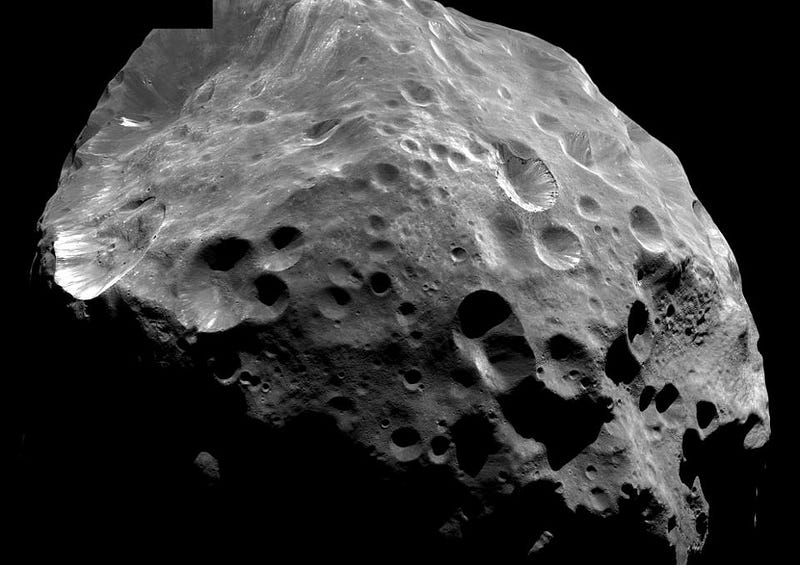

Iapetus also has a giant ridge along its equator: some 10 kilometers higher than the rest of the rocky, icy world. It isn’t rotating quickly enough to explain this, and the surface of Iapetus appears to be many billions of years old, so it likely isn’t recently coalesced debris, either. While many ideas abound concerning what causes this ridge, no one theory is the clear front-runner. There are many ways in which Iapetus is unusual for our Solar System, and there are quite a few mysteries about it that haven’t been answered.

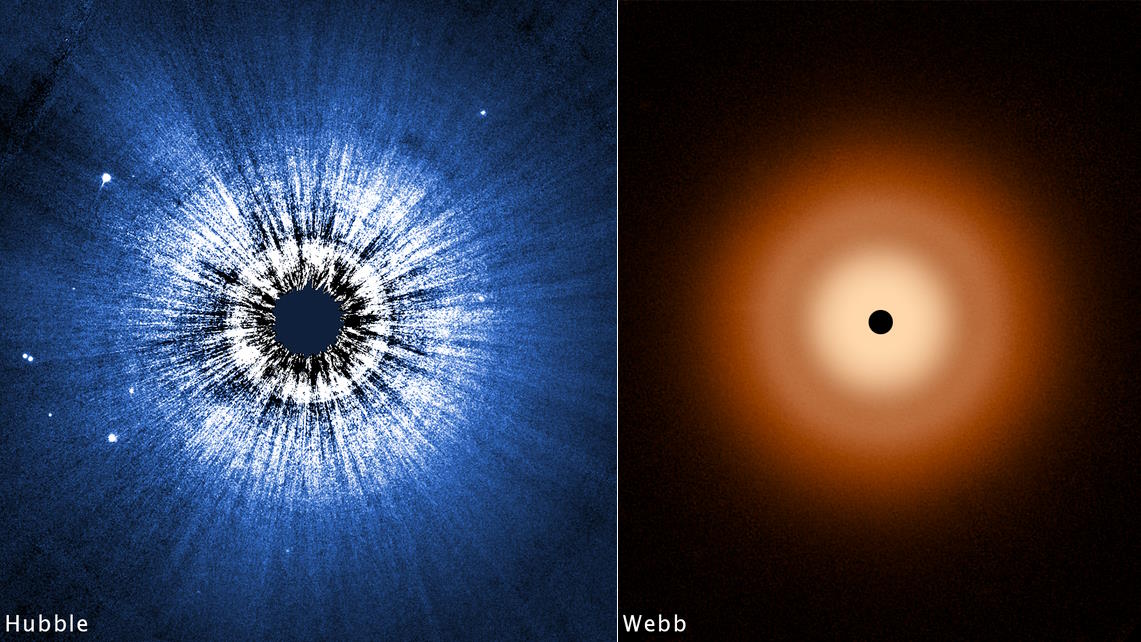

But one of them has been, more than 300 years after it was first recognized. Thanks to Cassini — the NASA mission, not the Italian scientist — we’ve actually gone to Iapetus itself to photograph it, finding that in fact one side looks like it’s been plowing into a dirt storm. Iapetus was very much two-toned, with one hemisphere a factor of ten-to-twenty times more reflective than the other. The situation was even more severe than Cassini himself had ever imagined, as the delineation between light-and-dark hemispheres doesn’t perfectly coincide with Iapetus’ orbit.

But this led to an even greater mystery: why would Iapetus appear this way?

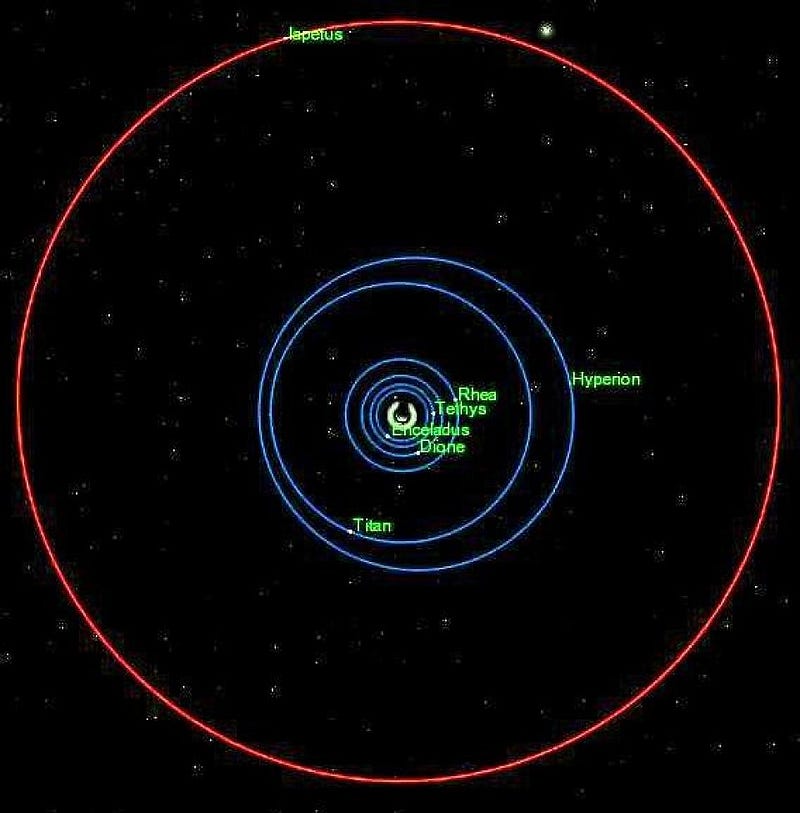

Iapetus, you see, is the outermost large moon of Saturn, orbiting twice as far out as any of Saturn’s other moons. What appears to be some type of dark debris that collected on the leading side — an effect similar to “bugs on a windshield” — would be an awfully bizarre explanation, since it’s well outside of the other major players in Saturn’s system, including Saturn’s rings. In fact, none of Saturn’s other moons display this feature; Iapetus is alone. Yet the culprit was about to be caught.

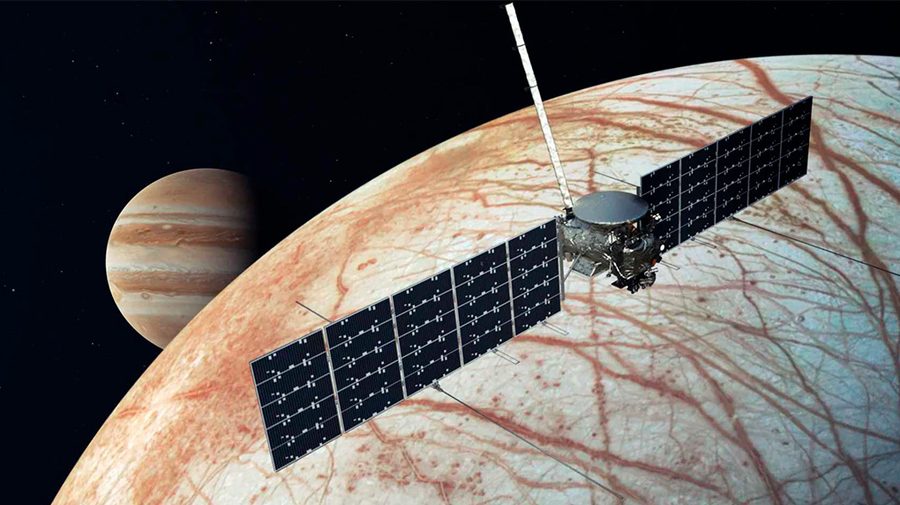

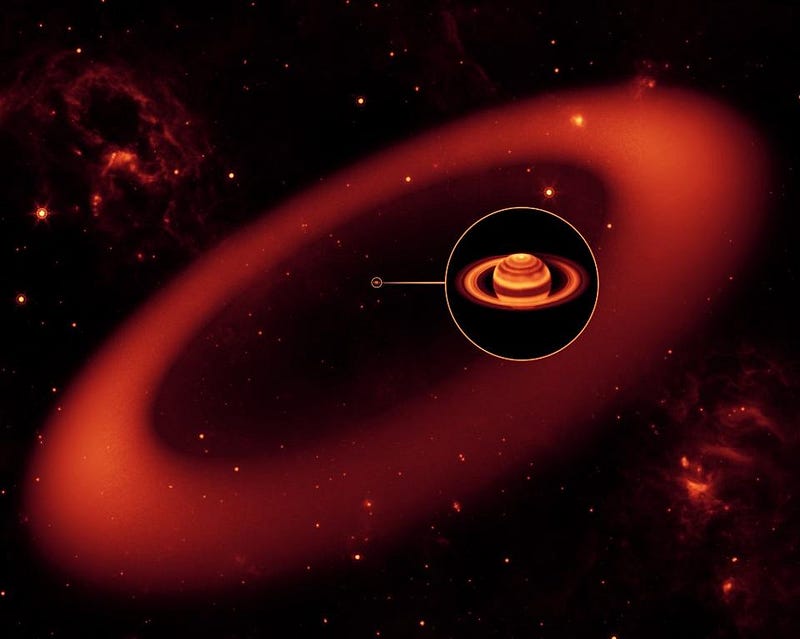

Even outer to Iapetus lies Phoebe, a smaller moon that’s most likely a captured object from the Kuiper belt. Unlike all of Saturn’s other moons, Phoebe orbits in the opposite direction, is far more distant, and most importantly, is very, very dark. It’s darker, intrinsically, than all the other major moons found orbiting Saturn, and is comparable to the dark portions of Iapetus. In addition, Phoebe has been emitting a steady stream of particles for a very long time, as the Sun’s radiation and minor collisions are strong enough to kick dust grains off of Phoebe’s loosely-held-together surface.

Thanks to infrared observatories like the Spitzer Space Telescope, we’ve been able to discover something incredible about Phoebe: it’s created its own ring around Saturn, larger, more diffuse and far less dense than any other ring discovered so far. The ring is so dramatically sparse — at seven dust-sized grains per cubic kilometers — and so huge in extent that even distant Iapetus plows through it in its orbit! Phoebe and its ring particles revolve clockwise around Saturn, but Iapetus goes counterclockwise, meaning that we do get the “bugs on a windshield” effect.

Over time, these much darker particles accumulate on one side of Iapetus and not the other, but that’s only the start of the story. If that were the only thing happening, the “bright stuff” on Iapetus, which is ice, would simply cover over the darkened Phoebe material in short order. While the darker material would accumulate, it would be under a layer of ice, meaning Iapetus would eventually appear entirely white.

But the same physics that causes a black car left in the Sun to be much hotter to the touch than a white car in the same conditions is at play on Iapetus, too. When this water attempts to condense, freeze and settle onto the light regions on Iapetus, there’s nothing stopping it. But when it lands on the dark regions, the heat from the surface is enough to sublimate (boil, directly, from a solid phase) the ice, rendering it capable of landing stably and permanently only on the side that isn’t covered in Phoebe’s debris.

The result? A two-toned, Yin-Yang world unlike any other in the Solar System. After more than 300 years, this is one puzzle of the Solar System that’s finally solved. The most unusual looking moon has a dark side, all thanks to a failed comet that was captured by Saturn long ago. Over hundreds of millions of years (or more), its debris built up on this lonely, outer moon, changing its color and how it absorbs sunlight. With no ice able to remain on that side, it remains destined for permanent darkness as long as the Sun continues to burn. The ridge and its orbital tilt remain mysteries, but the two-toned nature is one puzzle that’s at long last been solved!

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!