Ask Ethan #32: Are our students doomed to an inferior education?

As teachers begin using new and questionable methods, will students suffer and get left behind?

“Quite frankly, teachers are the only profession that teach our children.”

–Dan Quayle

As the first full week in April comes to a close, I’ve taken another look through the best of your submitted questions and suggestions, and chose one to be the subject of our weekly Ask Ethan column. This week’s topic comes all the way from Germany from Philipp, who asks:

In Germany, many teachers have adopted a new way of teaching children to write properly. The way is called “Writing by Reading” and essentially says: Write as you wish, you’re not bound by any rules. […] [R]ecently, this way of teaching has been heavily criticized, but not before it has been “tested” on several years of school children. Now, when I read things like that and when I see data which implies that children nowadays have much more trouble writing correctly, I am getting worried (as a father of three children; the oldest starting school next year) and I absolutely want my children to do well at school and not be hindered in their future career by getting the basics wrong. My question is: What can I actually do about it?

There are two issues at play here, and I want to take great care to separate them.

The first is the issue of literacy skills. Believe it or not, this has always — as far as I’m aware — been an issue of contention among educators. Now I’m really only familiar with how things work in the United States, but English is its own can of worms as a language, far more divorced from straightforward phonetics than a language like German. Nevertheless, when I was young and first in school, we were taught phonics: letters could make certain sounds, and combinations of letters in different situations could make a variety of sounds. The more you practiced (i.e., the more you read and wrote), the better you’d get at it. Words like “tough” and “bough” were challenging at first; English is a language full of exceptions.

But phonics — the power to sound out words based on how they were spelled and the individual sounds each letter made — could get you through an unfamiliar word well over 90% of the time. It was a very successful method for me and for pretty much everyone that I grew up with; even the people who were below-average readers recognized the usefulness of the method.

And then I started taking education courses at college when I was 21.

Now, this isn’t necessarily a knock on the education profession, although it’s going to sound like it to someone just doing a drive-by of this blog. We read a paper — published in a prestigious education research journal — decrying the abominable state of literacy in America, which noted that 50% of all seven-year-olds were reading at a below average level.

Think about that for a moment.

Yes, 50% were below average. And — although the paper didn’t say one way or another — my assumption is that 50% were above average, as well. Because in almost all samples like this (as a consequence of the central limit theorem), that’s kind of the definition of average. In other words, there was no education or literacy crisis, at least, not based on the actual information that was being used to argue that point.

But it didn’t much matter, because sometime in between the time I was learning to read to the time when I was graduating college, the powers-that-be had decided that phonics was the wrong way to start kids off, and that most schools in the country had replaced a phonics-based education with the newest educational fad: whole-word reading. This was based on the fact that the way adults read isn’t phonetic — we don’t sound out the words in our head as we see them — we simply recognize them for the words that they are. It’s why we can read jumbled text like so.

This system, of course, had a huge number of detractors: basically every parent in the country who had somehow successfully learned how to read. If their kids weren’t learning at least the same skills that they did when they were younger, aren’t they going to be worse off in the world? Surely knowing how to read — and how to sound out previously unknown words — is one of the most important and basic skills that a young reader needs to develop! But is that actually true?

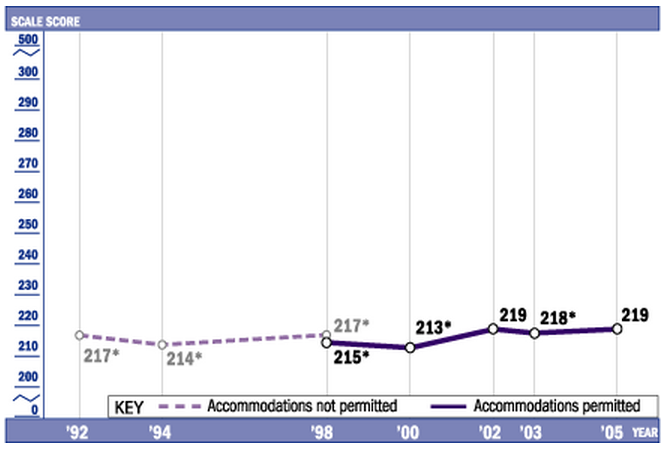

Well, you would ask, did it work? Did changing from a phonics-based approach to a whole-word approach positively affect reading comprehension? According to a big comprehensive study that tracked reading scores, here were the big results.

There was absolutely no change in overall literacy rates or skills. The tiny variations you see are completely statistically insignificant, and it turned out that the methods used to teach wound up not really making much of a difference in outcomes. And this kind of makes sense when you think about it: in the grand scheme of things, developing basic literacy skills is something that you’ll develop if you practice. The method isn’t nearly as important as the time and effort spent on getting it right. The only difference you’re likely to see is what details they’re better-or-worse at.

So for Philipp’s example — and I confess, this is the first I’ve heard of this particular emphasis — you’re probably correct to worry that your children will emerge as worse spellers. The thing that you might want to think of alongside that, though, is what they’re going to wind up better at instead, because they spent more time emphasizing those things. If they wind up as worse spellers but better, clearer communicators, with more organized ideas and clearer trains of logic in their written thought, is that a fair trade-off? Moreover, what’s more important to learn early on: how to spell or how to present your thoughts? I’m not certain, but — even without knowing the results of the research on this — I’m willing to bet that it’ll be a wash of sorts.

Now, that was the first major point. Based on my own experience as a teacher and educator (as well as a student, once-upon-a-time), your particular children may vary greatly based on this method: they may do much better or much worse than they would have under the method you were taught, but on average they’ll all wind up with roughly the same set of overall language skills at the same level that we had back when we were a comparable age.

Which brings us to my second point: what does it all mean?

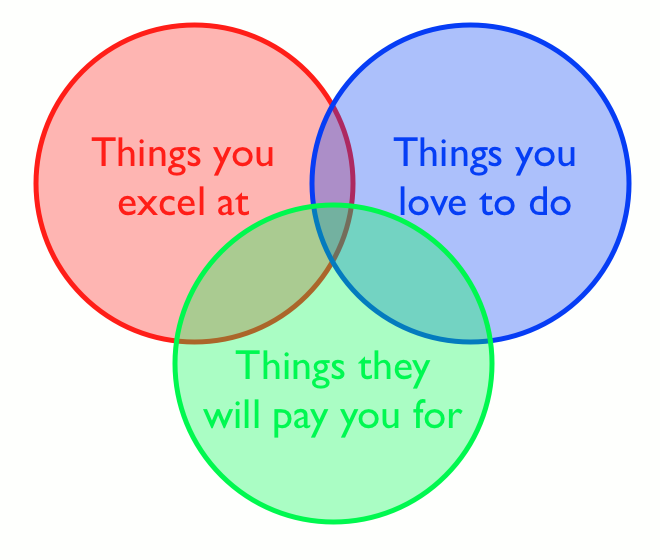

Consider the Venn diagram, above. I hate to reduce the entire experience of education and your career post-education to such a crude picture, but there it is. It’s very likely that the red circle of “things you excel at” is based in no small part on what you spent your time learning and practicing, and that’s something that changes somewhat not only from one individual to the next but from one generation to the next. Some people lament this and find it appalling; I had a 75-year-old teacher who couldn’t bear that kids these days didn’t know how to calculate square roots by hand. Well, I know how to do it now (and that’s fine), but was that the best use of my time and brainpower? Would I have been better off working on something different?

There’s no need to try and answer those questions; the fact is that — and I’ve alluded to this before — everyone goes through the world with their own unique toolkit of how to approach, attack and solve problems. Everyone has their own unique set of skills, and one of the things that we don’t typically talk about is that there are many good ways to learn and gain such a skill set. At the end of the day, you could’ve been taught other things instead of the things you were taught, but you most likely wouldn’t end up knowing more things or more valuable things, just different ones. That circle of “things you excel at” gets larger based on the work you put into it; it’s just a question of which direction it grows in. For the most part, all directions are good.

Notice how little that actually has to do with the following:

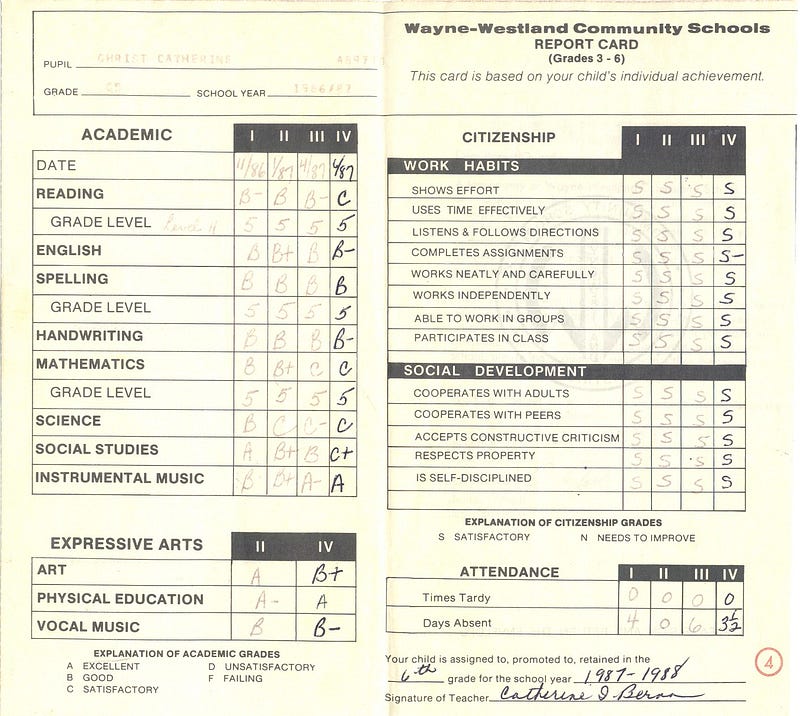

Report cards. Grades. How we normally “measure” how much someone has learned. It’s true that good grades can open some doors for you while bad grades can close some doors for you, but when real life comes knocking, your grades are completely meaningless (beyond perhaps getting your foot in the door) when compared to the simple question of what can you do? We don’t want a world where everyone excels at the same things, where there’s no diversity in education and where everyone works at exactly the same things at exactly the same level. The world already has your exact skill set, because that’s what you’ve brought into it. If the next generation comes out with a slightly different offering, that’s a good thing!

As long as you, your kids, or whoever the person in question is is expanding their skill set — hopefully in a way that overlaps with something they love and also with something that someone, somewhere will enable them to make a living doing — I don’t think you need to do anything about it. If there are essential skills that you feel they’re not learning, you can force them to spend time on them, but unless it’s something they themselves choose to inherently value, I personally don’t think it’s going to be a better use of their time than learning the things they do value.

So what can you do?

Help them find what they love and value learning about and let that be the thing they spend the most time on, help ensure that they have a well-rounded education and skill set and let it be a priority that they be at least somewhat competent at all of those things, and that they grow up to be good people with good values.

For my own part, yes, I notice that students even at the college level have certain deficiencies in grammar, spelling and communication that were very uncommon just 15 years ago when I was a college student. Their analytical, mathematical skills are somewhat weaker, overall, than they were back when I was a student as well. But they also commonly have skills — many of which are useful skills (e.g., computer-based skills, a deeper understanding of world and cultural history, better second-language skills, etc.) — that are superior to what the average student had just 15 years ago as well. And for the most part, it’s not a useful way to spend my time to judge the merits and demerits of what are, realistically, very minor differences. It’s more useful to treat each person like an inherently valuable individual, and help them grow in the direction that suits them best.

We all have our own unique toolkits and skill sets in this world, and we shouldn’t want it any other way. It’s only natural to worry that there are essential skills that the generation coming up isn’t getting, or to feel like there were so many things we learned that they’re missing. Well, there are, but as glad as I am that I learned typesetting, woodworking and technical drafting as part of my education when I was younger, I can also appreciate the value in things that I didn’t learn. As long as they are learning, they are being challenged and they do have an affinity for what they’re working on, I think your kids will be just fine. (And it definitely helps that they have a parent who cares about them and their education!)

And that’s what I think about focusing a student’s education on different valuable aspects — but valuable aspects nonetheless — than the ones we valued when we were young. I hope you enjoyed this week’s Ask Ethan, and as always, if you have questions or suggestions for the next column, let’s hear them. You just might be our next featured entry!

Want to have your say? Do it, at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!