Messier Monday: Virgo’s brightest galaxy, M49

A galaxy very different from our own may hold the key to seeing what our far future looks like.

“We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.” –Carl Sagan

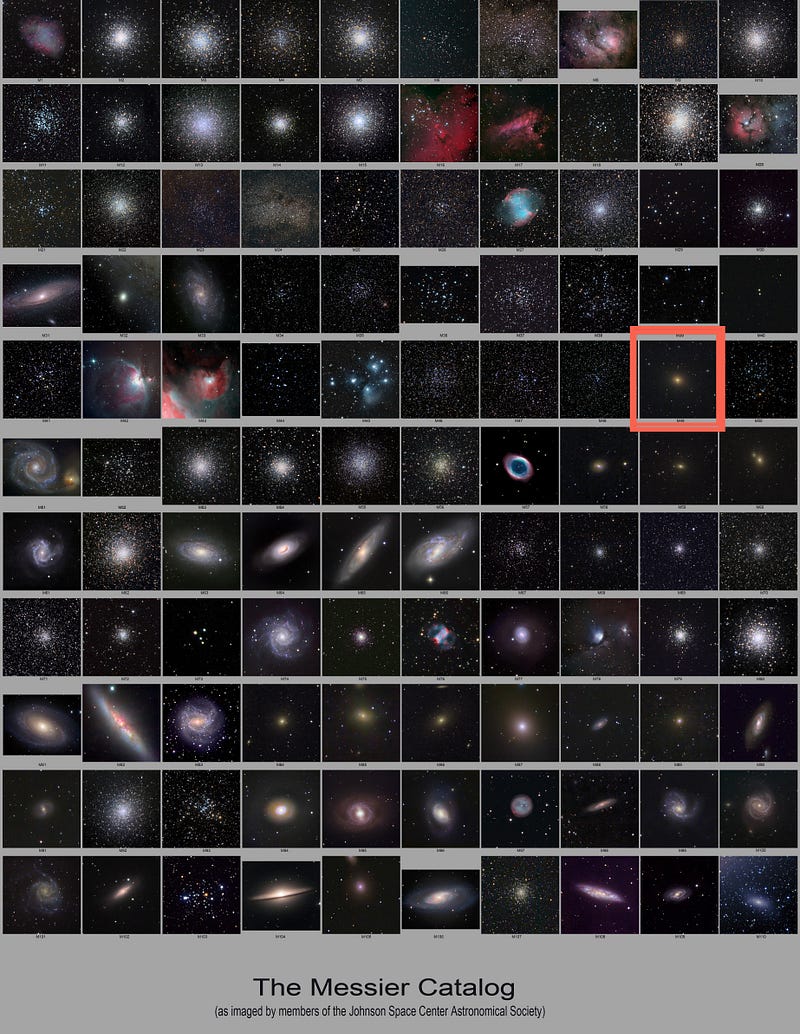

Every Monday on Starts With A Bang is Messier Monday, where we profile one of the 110 deep-sky wonders that makes up the Messier Catalogue. In the 18th Century, there were no accurate, high-quality catalogues of fixed objects in the night sky. Originally designed to assist comet hunters in their quests (to avoid confusion), this is now useful for skywatchers seeking out the brightest and most spectacular views of the Universe visible through pretty much any telescopic equipment here on Earth!

On a moonless night (like tonight mostly is), some of the fainter, extended objects whose light is diffusely spread over a larger area of sky are more clearly visible. With the coming onset of spring — if you can brave the cold temperatures — the richest cluster of galaxies rises to prominence in the early part of the night: the Virgo Cluster.

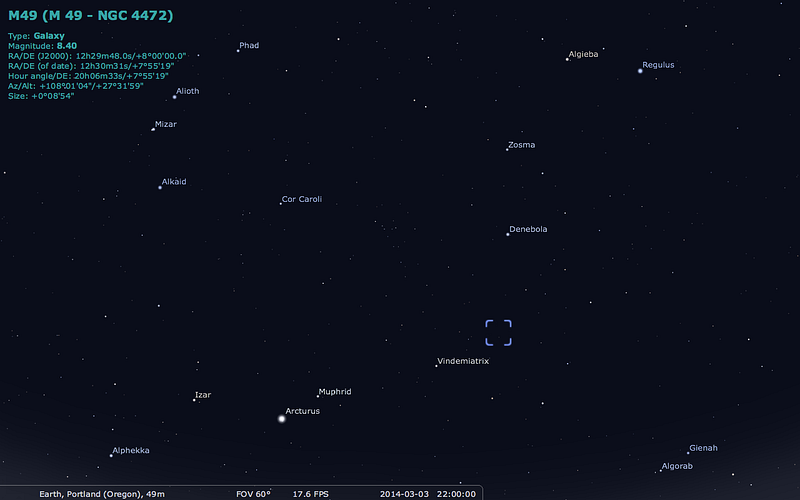

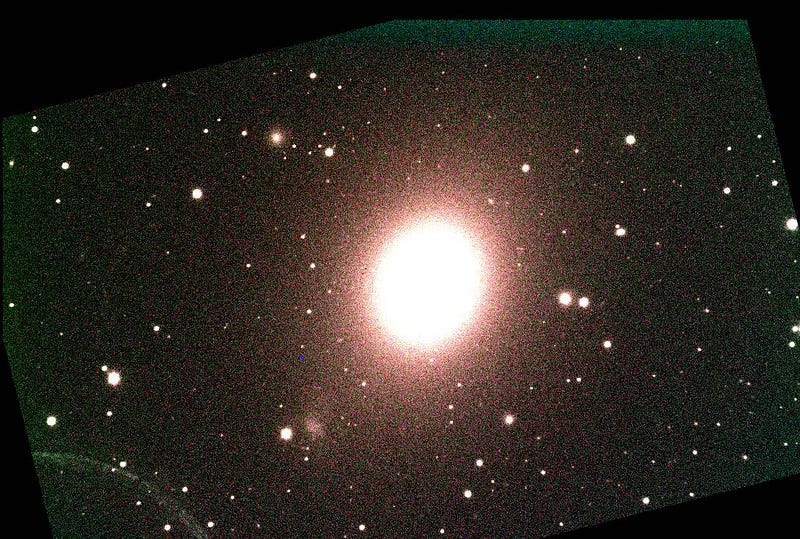

Today, I’m proud to showcase the brightest galaxy in that direction: the giant elliptical galaxy Messier 49. Here’s how to find it.

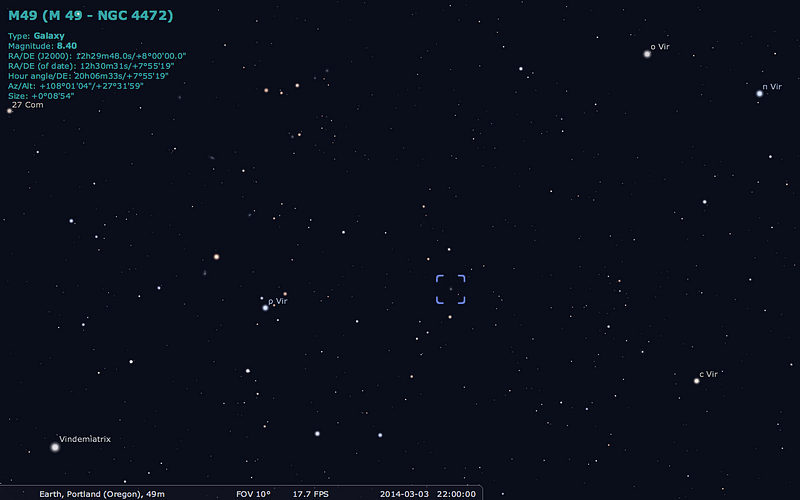

After sunset in the northeastern skies, you should be able to find not only the Big Dipper, but also the bright orange giant Arcturus, which you can locate by following the “arc” of the dipper’s handle. The constellation Leo hovers nearby, and if you move from Arcturus towards Leo, you’ll run into two prominent stars on your way: Muphrid first, very close to Arcturus, and then Vindemiatrix, which is in the constellation of Virgo.

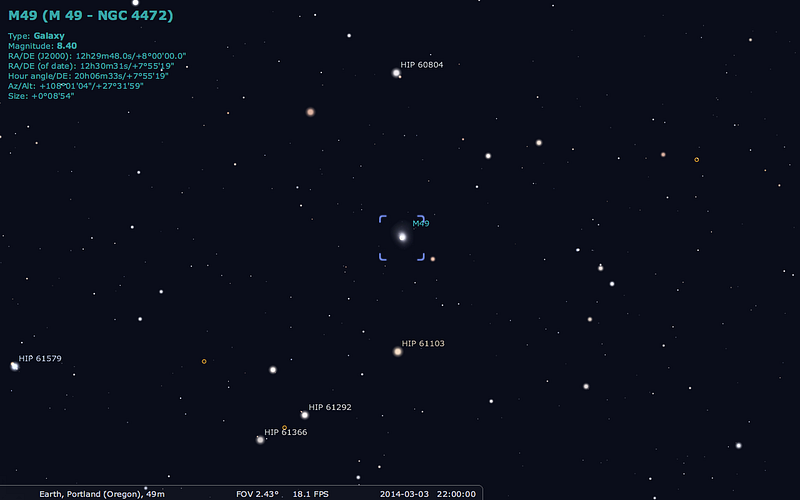

If you would continue that imaginary line, from Arcturus to Vindemiatrix, for about another four degrees, you’ll wind up right at Messier 49. But for a little help, there’s another (fainter, but still naked-eye) star that helps point the way: ρ Virginis. If you follow that same path and look (moving a tiny bit south) for the star pattern, below, through either binoculars or a low-power telescope, you should find Messier 49 right in the center.

This faint, nebulous and unremarkable fuzzball is not only the brightest member of the Virgo cluster of galaxies, it was the very first galaxy in that cluster discovered, by Messier himself in 1771. He recorded it as a:

Nebula discovered near the star Rho Virginis. One cannot see it without difficulty with an ordinary telescope of 3.5-feet [Foot-Length]. The Comet of 1779 was compared by M. Messier with this nebula on April 22 and 23: The comet and the nebula had the same light. M. Messier has reported this nebula on the chart of the route of the comet, which appeared in the volume of the Academy of the same year 1779.

It’s easy to see why a galaxy like this would, perhaps, be confused with a comet through a small telescope.

It looks like it has a bright central nucleus that fades away as you move farther outwards, similar to what a comet would look like if it was headed straight towards you.

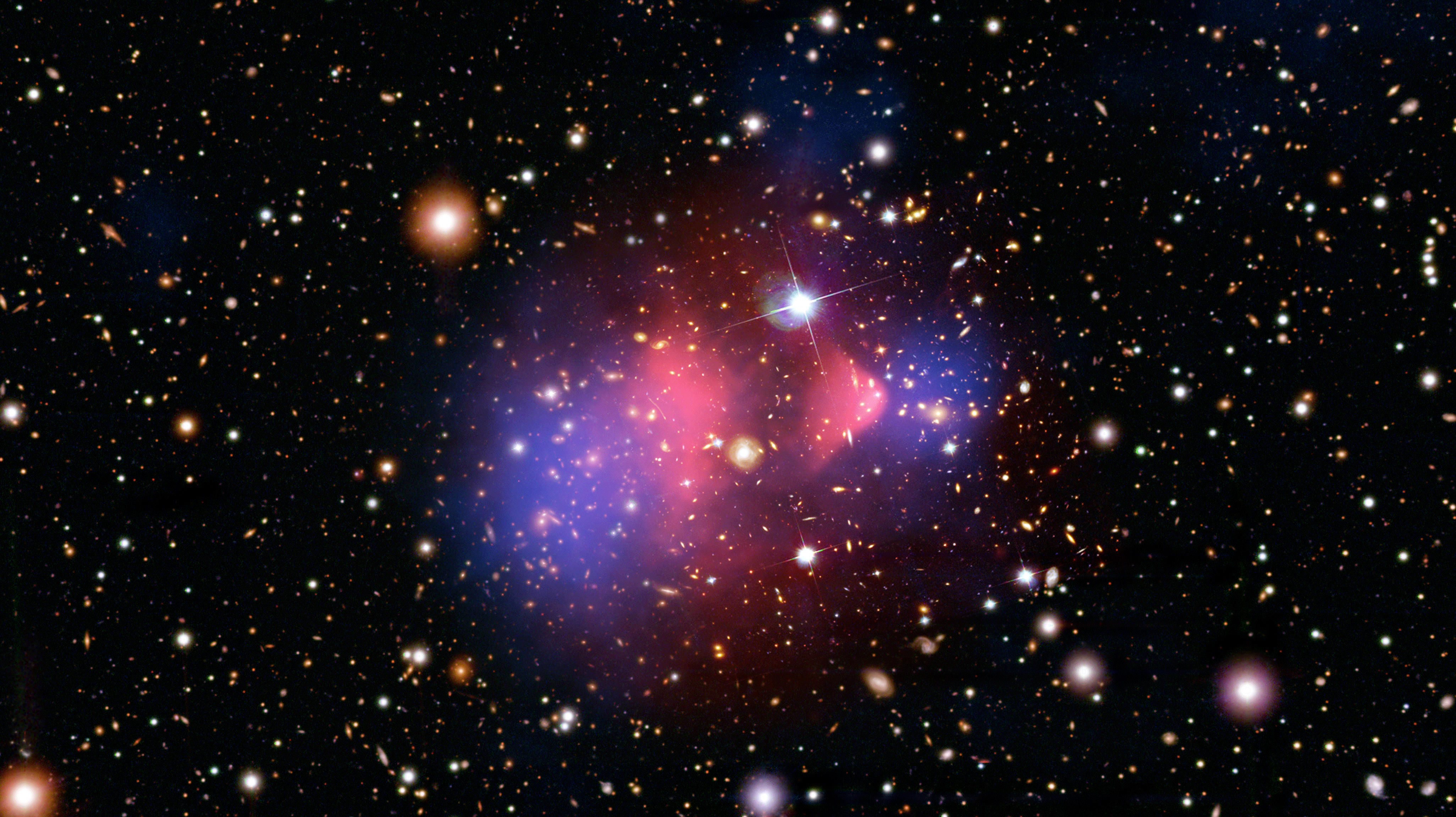

The difference, of course, is that comets change their positions over time, and brighten or dim as they move towards (or away from) the Sun, while this object has remained stationary and at constant brightness for nearly 250 years since its discovery. You might also be a little surprised at the above image, because when I say “cluster of galaxies,” you probably think of this.

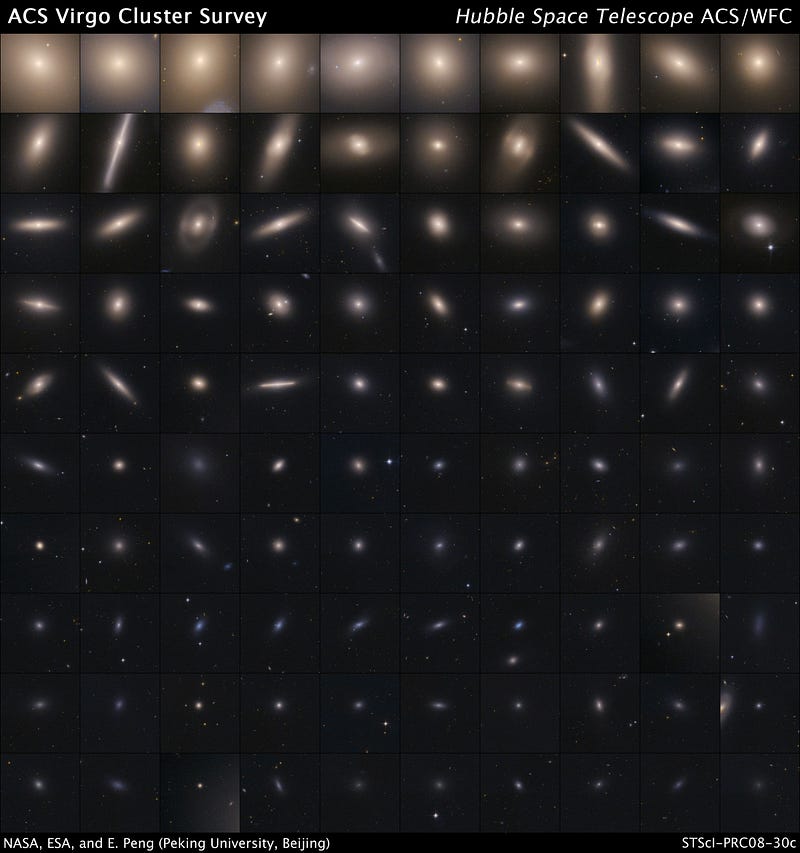

And this is what the Virgo cluster of galaxies looks like. At least, what a portion of the cluster looks like. You see, the Virgo cluster is the nearest giant cluster to us, with well over 1,000 confirmed galaxies (and probably closer to 2,000). But at a distance of roughly 50-55 million light-years on average, these galaxies span many degrees across the sky.

The main clump of the Virgo cluster is shown above, and indeed, it contains the majority of the cluster’s mass. But about 5 degrees away lies the clump centered on Messier 49, which contains about 10% the mass of the larger, main clump.

http://www.ngc7000.org/ccd/gal-virgocluster.html#m49.

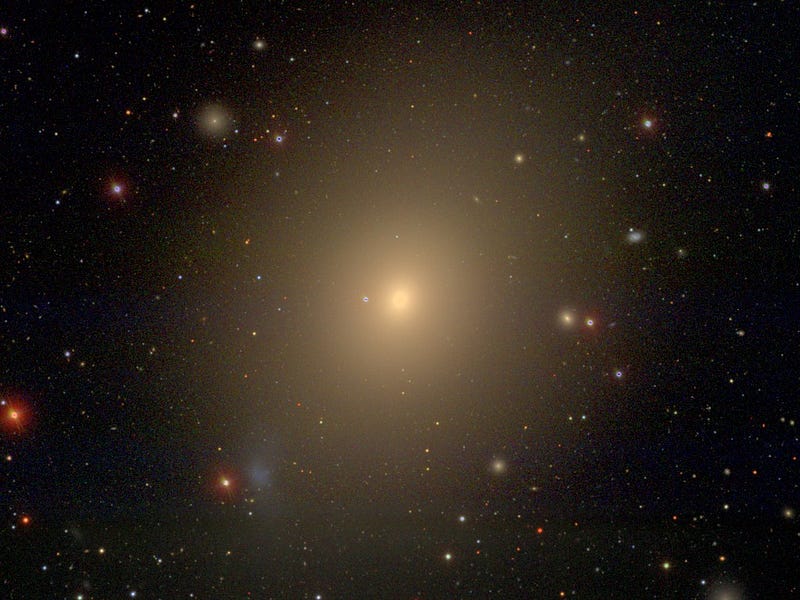

But there are a number of reasons to be excited by this galactic behemoth that dominates its part of the night sky! First, at its distance, it’s the brightest galaxy visible from Earth; no galaxy equally or more distant is as bright to our eyes, even scanning the entire Universe!

Second, it’s very big: 160,000 light-years across in the direction we can see, although it’s possible that the line-of-sight direction is even larger. In fact, if you trace out the full extent of the galactic edges, it extends for around 800,000 light-years, or about eight times the extent of our Milky Way.

And third, it’s very yellow!

The average color of stars in this galaxy is much redder than even our Sun is, implying that it’s been about 6 billion years or so since the last major episode of star formation graced this galaxy. And finally, as you can perhaps see from the image above, there are a huge number of smaller, satellite objects, including many dwarf elliptical galaxies. Perhaps most impressive is the fact that unlike our own galaxy, which has maybe 150-to-200 globular clusters, Messier 49 has about 6,000!

But you may, looking at images like this, notice a faint trail of debris coming from this galaxy. Indeed, that’s real, and due to the fact that it’s gravitationally interacting — which, for pretty much anything in its clump, means “its future victim of galactic cannibalism” — with a much smaller galaxy!

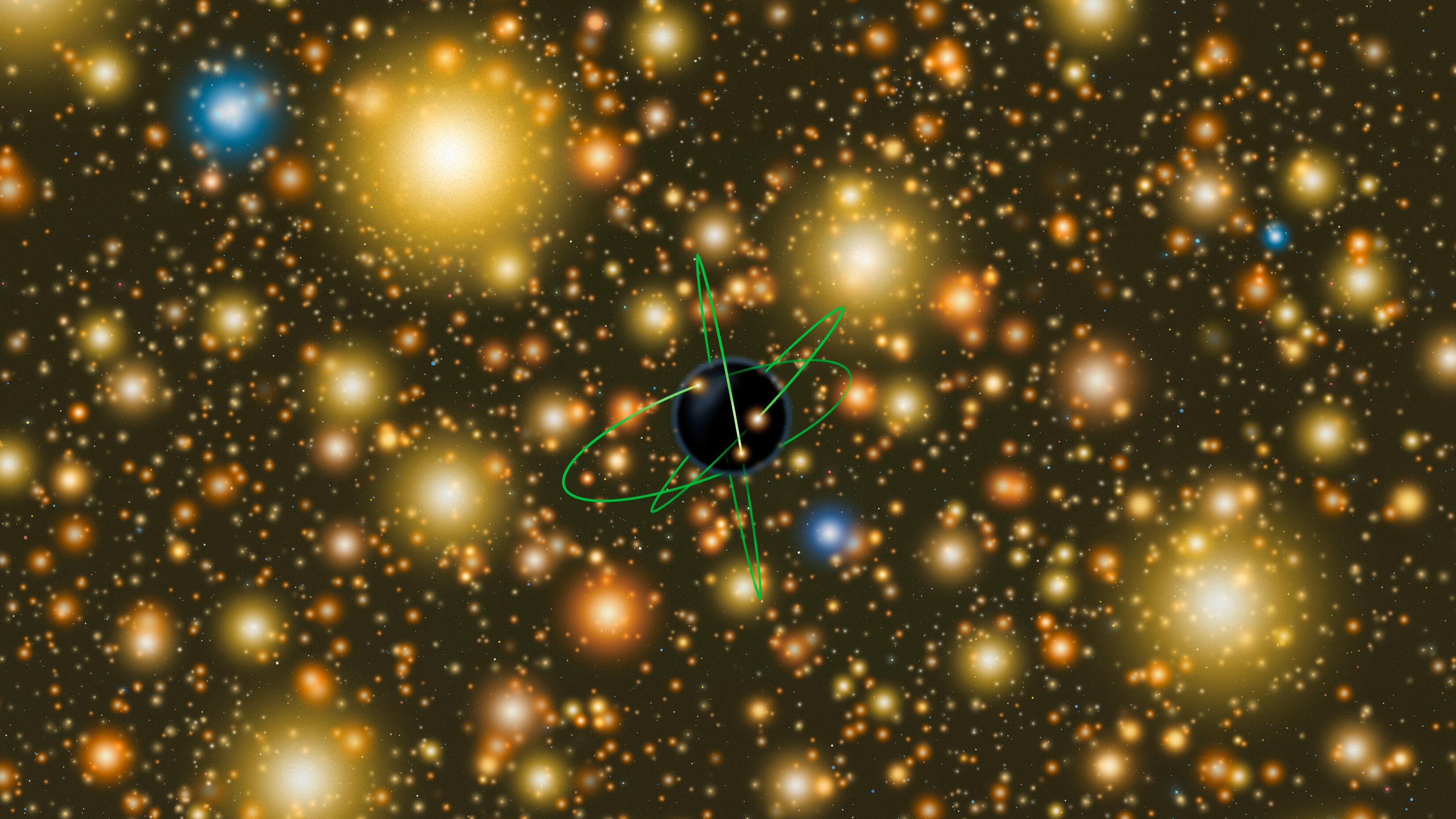

And things get more and more exciting when we think about the core of this monster.

The nucleus emits X-rays, which are a telltale sign of a central, supermassive black hole. But unlike galaxies like the Milky Way, which tend to have black holes a few million times the mass of our Sun, the one at the center of M49 is over half a billion Suns, at 565 million solar masses!

And finally, long ago — back in 1969 — the lone supernova ever seen in this galaxy went off; it’s been quiet ever since.

And, as always, the greatest view of Messier 49 comes from the Hubble Space Telescope. It’s difficult to remember, looking at the “fuzz” and haze associated with this galaxy, that it’s made up of stars, and that every faint gradation in brightness is actually due to a greater number of stars.

Have a look through just a slice of this picture at the original, full resolution, and notice the background (and foreground) galaxies poking through the background, and ponder just how many stars must be inside that central nucleus of this behemoth!

This may very well be what the far future of our own galaxy — after the merger with Andromeda completes — will look like. And with that, we’ll bring today’s Messier Monday to a close! Including today’s object, we’ve profiled the following deep-sky wonders:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Have a favorite you’d like to see? Let us know, either here or over at the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs!