How is fascism distinct from other extreme ideologies? These 10 traits offer clues.

- Dr. Jason Stanley, a professor of philosophy at Yale, lays out the 10 traits of a fascist movement.

- Although authoritarian regimes may exhibit some of these traits, Dr. Stanley proposes that they only become fascist when they demonstrate all of them.

- This definition of fascism is broader than others but it is also easier to apply.

The trouble with discussing political philosophy is that the definitions of philosophers often break down when you try to describe leaders and movements in the real world. Contradictions begin to arise, the nuances of policy begin to enter into the discussion, and questions arise over whether the candidates you see in media are really as bad as others think.

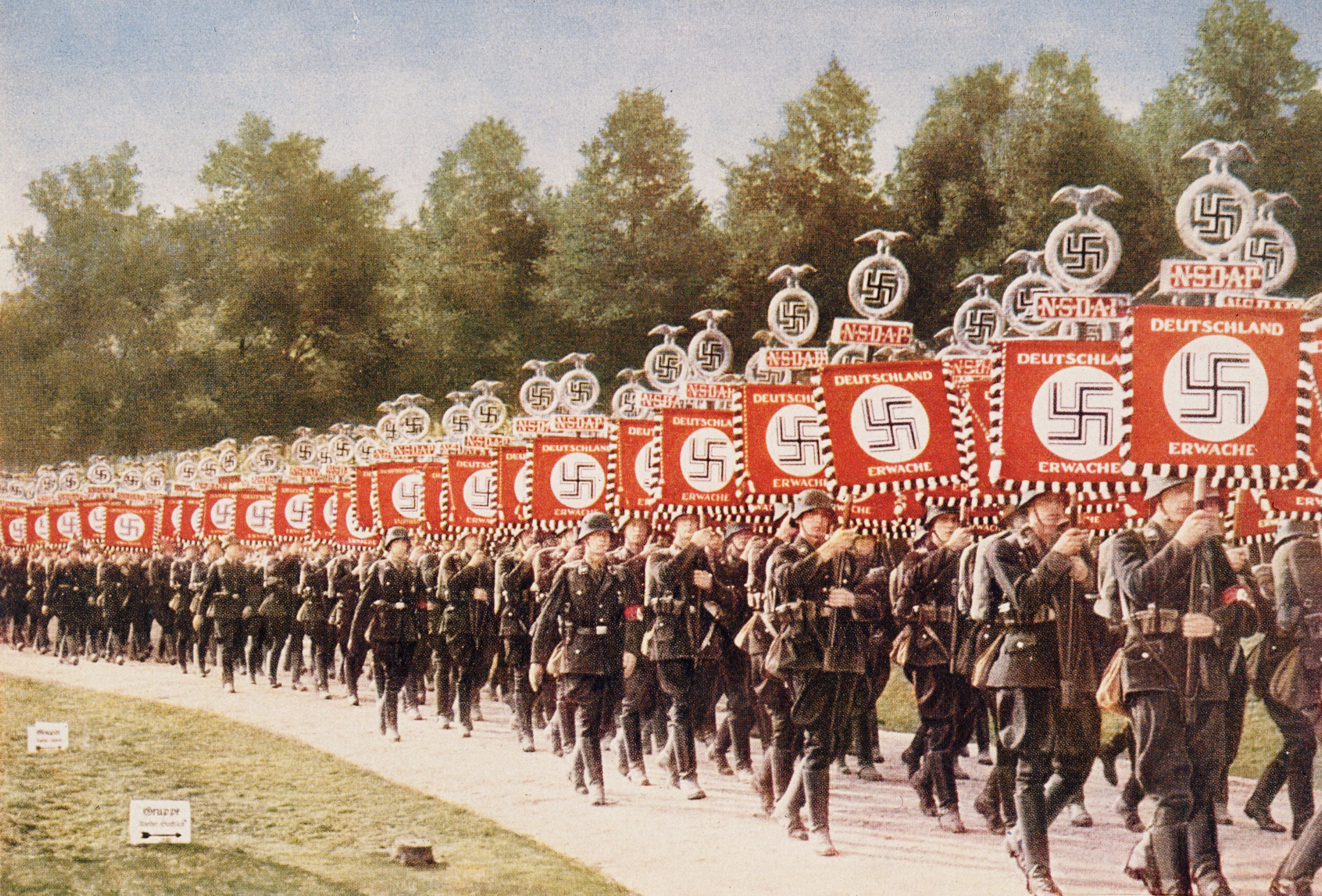

Luckily, some philosophers have turned their attention to fleshing out definitions of political ideologies in ways that help them become less abstract and more concrete. One of these thinkers is Dr. Jason Stanley. He is a professor of philosophy at Yale, an expert on propaganda, and the child of refugees who fled Europe as fascism reared its ugly head. In his book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, he proposes that the notoriously slippery ideology comprises 10 traits — many of which can be found in authoritarian regimes which are not fascist — and that the combination of these traits in a regime or movement gives rise to fascism.

These traits are:

The Mythic Past: The creation of a mythical, idealized past to look to as a moment of national glory to which the country should return. While often based on some easily exaggerated moment in history, it needn’t be based on much at all. Leaders in fascist Italy placed a higher value on the myth itself than its historical veracity, for example.

Propaganda: While many political philosophies use propaganda, fascists lean on it to establish a sense of “us and them,” and to frame “them” as an existential threat to the nation.

Anti-Intellectualism: The “them” typically include intellectuals or sources of expertise that might disagree with the leadership of the government or the fascist movement. Beyond intellectuals in the humanities, leading figures in the hard sciences can also be targeted if they go against what the leader needs to be true.

Unreality: Fascists tend to ignore details that might trouble them and define truth as whatever the leader declares it to be. This can make propaganda more effective because it allows for a leader to get their followers to ignore problems that might derail a more reality-based movement. It can also lead to things like the Nazis trying to find Atlantis.

Hierarchy: Pretty much any fascist movement will establish a hierarchy of humanity with a particular group — be it a race, religion, sex, gender, or nation — on top and everybody else below. Equality is denied and the value of the alleged dominant group will be parroted for all to hear.

Victimhood: Despite the claims of superiority, the fascist tends to also claim this group has been victimized by others — say, stabbed in the back while they were about to win World War I — and that bold action is needed to right this “wrong” and restore the hierarchy. This also tends to make equality look like discrimination against a group that isn’t being discriminated against.

Law and Order: Fascists often promise to bring law and order to a nation, though they often end up more corrupt than anybody else.

Sexual Anxiety: Like other right-wing movements, fascism tends to play on fears of and prejudices against homosexuality. Fascist politicians often frame themselves as protectors of women and children in the face of fanatic homosexuals out to harm them.

Sodom and Gomorrah: Many authoritarian, right-wing regimes gather support from the countryside by painting the urban parts of the country as the source of decadence, cosmopolitanism, sin, crime, and moral decay. Urban elites are contrasted with the “real” citizens living a wholesome, traditional life in the country.

Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” was written above the gates at Auschwitz. Not only a dark warning, it expresses the fascist notion that only by working for the nation does a person have value or deserve to be treated as a person. Hard physical labor is often highly valued, while those working in academia or other less physical professions are often looked down on.

Still, a nation that possesses only one or a few of these traits is not fascist, as Dr. Stanley told Big Think:

“Each of these individual elements is not in and of itself fascist, but you have to worry when they’re all grouped together, when honest conservatives are lured into fascism by people who tell them, ‘Look, it’s an existential fight. I know you don’t accept everything we do. You don’t accept every doctrine. But your family is under threat. Your family is at risk. So without us, you’re in peril.’ Those moments are the times when we need to worry about fascism.”

How does this compare to other ideas of fascism?

Dr. Stanley’s definition of fascism, as the blend of the above ideas, is a bit broader than that of other academics. We’ve considered that of professor Roger Griffin, which is significantly narrower; he limits its application to Italy and Germany during the darker parts of the 20th century.

While Dr. Stanley might be able to apply his definition more widely — say, against the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet — Griffin would say that Pinochet was fascist adjacent, a pseudo-populist despot who lacked certain elements that make authoritarian right-wing governments truly fascist. (This distinction may have been lost on those his regime threw from helicopters, however.)

It’s also worth noting that leftist political movements can also be authoritarian and violent; tens of millions of people died under the regimes of communist leaders like Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. However, most definitions of fascism would not categorize communist regimes as fascist, in part because commustist movements generally reject private property and the concept of the nation-state.

Dr. Stanley’s definition of fascism may be broad and categorize despots as fascists who would otherwise not make other lists. But his definition has the advantage of being understandable and useful for a citizen in a country that is backsliding from liberal democracy toward far-right, authoritarian nationalism. It is one framework for understanding the ideas that fueled some of the most violent political movements in human history.