Why Controlling the Light Around You Is Critical to Your Health

For two years of my young adult life, I worked in commercial operations for the Discovery Channel. Nine hours a day, five days a week, I sat in its midtown Manhattan office attempting not to fall asleep. Row upon cubicle row was draining, yet something else drugged me: the lights.

Unnaturally bright florescent bulbs hung over our heads forty-five hours every week. By my next job as a magazine editor, I was pleased that my office was lamp-powered. Having control over the light around you is critical to your health.

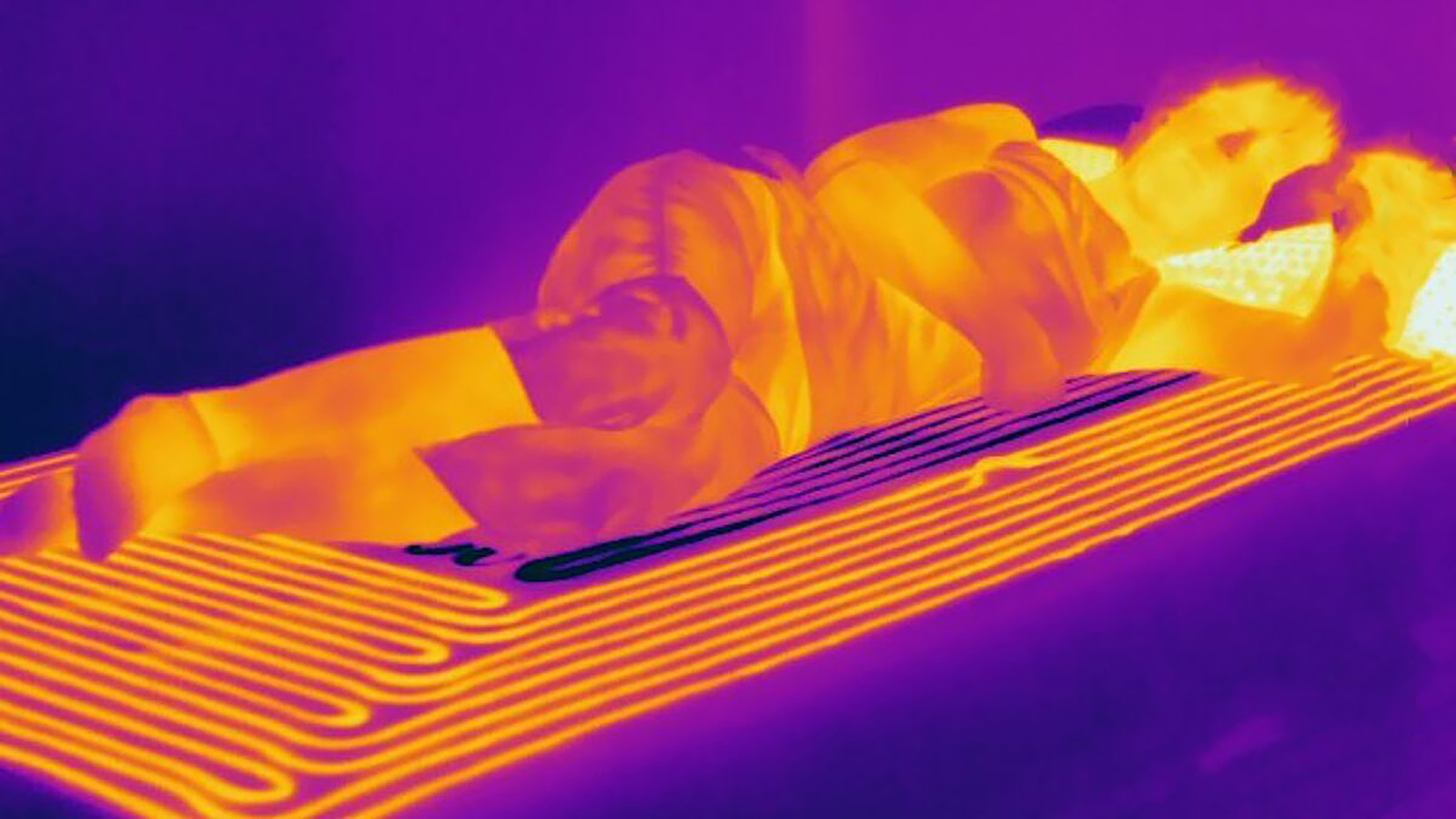

We know that circadian rhythms are important for our physiological functioning, and that light plays an essential role in this daily rhythm. Thanks to electricity we’ve hacked that process. In terms of agriculture this is not a bad thing; we can better manipulate crops for greater yield. But we’re not plants. A new study shows just how bad artificial lighting is for the human body.

According to the report, conducted at the Netherlands’ Leiden University Medical Center, mice kept under constant light caused “pro-inflammatory activation of the immune system, muscle loss, and early signs of osteoporosis.”

While it’s improbable that a human would be subjected to round-the-clock artificial lighting, researchers warn that this information is especially pertinent to the aging population, where bone density loss and inflammation are common markers of disease.

Inflammation increases when we don’t sleep; lighting, especially blue light from our devices, has been implicated in shutting down melatonin production, which also affects how long and deeply your rest is. Being that stress and inflammation are often concurrent, keeping your phone or tablet off for an hour or two before bed ensures better quality and quantity of sleep.

Harvard neuroscientist Anne-Marie Chang discovered that the light from our devices extends not just to bedtime, but the following morning. She compared readers flipping through a paperback to those using a tablet, and found that

Participants who read on light-emitting devices took longer to fall asleep, had less REM sleep [the phase when we dream] and had higher alertness before bedtime [than those people who read printed books]. We also found that after an eight-hour sleep episode, those who read on the light-emitting device were sleepier and took longer to wake up.

A number of fixes have been proposed. Amber light does not affect circadian rhythm as much as blue light; changing out some bulbs, especially around your bedroom and bathroom (anywhere you travel at night), helps you fall asleep faster if you wake. Apps such as f.lux dim your devices for you, though you can also control the dim on your own in settings—keeping the brightness dialed down is a good idea regardless of time of day. And that good old paperback might just be the call, especially at night.

Of course, there’s the easiest fix of all: put your device down, especially in the evening. Keep your house lowly lit when possible, with gentler bulbs. Avoid florescent lights whenever possible. We like to think of technology as forward progress, but as far as we’ve come, we can’t forget what got us here. Sunshine still reigns supreme.

—

Derek Beres is working on his new book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health (Carrel/Skyhorse, Spring 2017). He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch @derekberes.